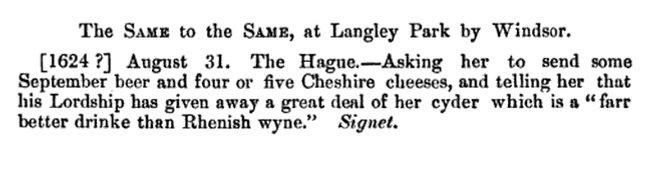

September ale. You will recall a few days ago I wondered what it was. I still am. If you look back you to that post, will see a fairly early Victorian, Walter Thornbury, in 1856 painting a fairly ripe picture of an Elizabethan manor in which the stuff is mentioned. Above snippet references September beer, not ale. It is from a summary of the Vere and Holles Papers recorded in the fabulously named Report of the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts, Volume 13, Part 2 published by Great Britain’s Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts in 1893. The first “same” above was Francis Wrenham while the second is Lady Vere. She is the wife of Sir Horace Vere, and Wrenham was their secretary / staffer of sorts. These 1620s letters are not unlike that of Issac Bobin to his master of 6 September 1720. Sir Horace was on business in Holland on behalf of the Earl of Southampton at the time. AKA people of note. It meant something. But what?*

My first instinct – that “these September thingies must be something” – is quickly and deeply dented. Little or no other references to chase. Probably it’s likely whatever was in the barrel rolled out then, maybe noted for its strength… perhaps. Then I realized something else. I started nosing around the RRCHM, vol 13(2) and just searching for references to “ale” and “beer” in themselves. Boom. Many references. Many. More for “hops” too.

What is this thing? It’s quite a remarkable bit of work to have been undertaken, especially for a public body. The Historical Manuscripts Commission (“HMC“) was established in 1869 to survey and report on privately owned and privately held records of general historical interest. In the early volumes, the records of government, universities and great houses are described. Consider just the index of RRCHM, vol 1 to get a sense of the scale of this project. A daunting yet tantalizing scale for anyone prone to search for words like “ale” or “beer” or “hops” in digital archive search engines.

Over 200 volumes were published before the project was discontinued in 2004. It’s full of amazing things. For example, in what I now affectionately call HMC13.2, we find the text of a travel diary related to Thomas Baskerville’s jaunts around England in the 1680s. It’s full of images like this one at page 303:

As to the town of Winchcombe, when the castle had its lord, and the abbey its abbots and monks to spend the estates and income of both places here, then here was more to do that at present, yet the town for the bigness is very populous, and the people of it in their callings very dilligent to get their livings. Here in a morning at 4 o’clock I saw many women of the older sort smoking their pipes of tobacco and yet lost no time, for their fingers were all the while busy at knitting, and women carrying their puddings and bread to the bakehouse lose no time but knit by the way. Here also lives in this town an ingenious cooper or carpenter who makes the best stoopers with a screw to wind up the vessel gently so that the liquor is little or nothing at all disturbed by that motion. We lay at the sign of the Bell, Mr. Houlet, a very respectful man our landlord, and his wife, who gave us very good entertainment, and seldom fail of good ale, for they have very good water in their well. They keep market here on Saturdays and have afair on St. Mark’s day and another on the 17 of July to which many good horses are brought to be sold.

We learn from Baskerville at HMC13.2p266** that from Bury to Beccles the “country afl’ords good and well tasted beer and ale, both in barrels and bottles” as well as, immediately after, how a man plowed with two horses “with great dexterity, turning very nimbly at the land’s end.” March beer is mentioned twice, once near Faringdon in Oxfordshire (“strong march beer”) and again at Pumfret or Pontefract 18 miles from York. But not September. Ale or beer. In Gloucester, Baskerville met one Langhorne, the keeper of the prison who “entertained us kindly and gave us good ale.” He also noted:

The best wines to drink in Gloucester are canary, sherry, white wine, for we neither drank nor heard of any good claret in town, but Gloucester surpasses this city for all sorts, where not long before we drank excellent canary, sherry, and claret, canary 2 shillings, sherry 1s. 8d., claret 1s. as good as in London, but for cyder and ale Gloucester doth surpass Worcester, for here we had excellent red-streak*** for 6d. a quart, and good ale 2d. a flagon. Here the people are wise and brew their own ale, not permitting public brewers; for curiosity of trades seldom found in other towns, here are 2 or 3 hornmakers that make excellent ware of that kind, viz. :— clear horns for drinking, powder-horns, ink-horns, crooks, and heads for staves, hunter’s horns, and other things.

It goes on. One town is praised for the clear well that makes the ale while the next is flagged for its brackish water. Note to file: be wary of the Three Cranes inn at Doncaster even if Charles stayed there. Brackish spring. Plus, at a groat a flagon, it’s twice the price of Gloucester ale. Now, consider one last image, this of harvestime in Kent from 1680 at HMC13.2p280**:

And now to speak a little in general of Kent. It is one of the best cultivated counties of any in England, and great part of my way that I went being through delicious orchards of cherries, pears, and apples, and great hop gardens. In husbandry affairs they are very neat, binding up all sorts of grain in sheaves; they give the best wages to labourers of any in England, in harvest giving 4 and 5 shillings for an acre of wheat and 2s. a day meat and drink, which doth invite many stout workmen hither from the neighbouring country to get in their harvest. So that you shall find, especially on Sundays, the roads full of troops of workmen with their scythes and sickles, going to the adjacent town to refresh themselves with good liquor and victuals…

Fabulous. You can imagine the packed dusty road taken from field to alehouse. And this all, of course, also presents a problem. This is the September of my fifty fifth year. Do I have time to go off doing this word searching and rearranging of information to present a deeper expression of the later end of the early modern English relationship with brewing and all its facets? Yet, it might explain what September in fact means. And what else do I have to do? What indeed.

* Update: a play in 1614 also includes a reference to “September beer” in Act Three as you will see if you click to the left. The full text of The Hog Hath Lost His Pearl can be found here. Again, like the letter of a decade later, people seeing the play knew the reference meant something. But what?

Update: a play in 1614 also includes a reference to “September beer” in Act Three as you will see if you click to the left. The full text of The Hog Hath Lost His Pearl can be found here. Again, like the letter of a decade later, people seeing the play knew the reference meant something. But what?

**I have immediately fallen deeply in love my new code for citation so get used to it.

***Redstreak

I’m not sure why no one else has chimed in on this, but my guess is that “September Beer/September Ale” is really just October Beer (sometimes also known as October Ale), which is probably most famous for being the likely forerunner of Pale Ale for India (better known as the beer that both saved and destroyed craft beer). It is the autumnal partner to March Beer, which you also have found references to.

I have recommended Pamela Sambrook’s “Country House Brewing in England, 1500-1900” multiple times to you, and I’m going to do so again. There is an excellent section on October Beer and the various uses of the terms “ale” and “beer” through the centuries and the distinction between the uses of these terms in an urban commercial brewing setting versus a country house brewing setting. I would argue that your Elizabethan references to September beer are from the home-brewed country house setting, which Sambrook describes in great detail:

“Until perhaps the seventeenth century the word ‘ale’ referred to unhoped fermented malt liquor, what Andrew Boorde referred to as the natural drink of an English man. ‘Beer’ – the ‘naturall drynke for a Dutch man’ – was the hopped malt liquor introduced from the Low countries in the fifteenth century. Since the new fashion for hops took time to spread to the country districts, the word ‘ale’ gradually came to be applied to the country drink, even though it might be hopped, and ‘beer’ the product of town breweries. … In the context of country house brewing, the terms were used in a slightly different way. The private house produced only a restricted choice of liquors. Their main concern was with various strengths of what would be generally called in the eighteenth century ‘ale’; porter and the heavier beers were rarely brewed. In this specialized rural world the word ‘ale’ seems to have been used to describe the first-drawn worts of each brew; the word ‘beer’ was used for the later worts of the same brew, products either of a second or even a third mash after the first worts had been run off. In other words, ‘ale’ denoted the quality drink of higher strength, whilst ‘beer’ referred to weaker household, table or small beers.” (pp. 17-18)

Beer “was weaker, and made with more water than ale using the same amount of malt. It could be weaker because it benefited from the stabilizing effect of hops. Strong malt liquor is more stable than weak, and unhopped ale derived its keeping qualities from strength rather than hops, so that later, when hopping became universal, the habit prevailed of calling the first stronger worts ‘ale.’” (p. 111)

“The difference in strength certainly persisted in the country house world, for as late as the 1920s the distinction was still known at Hickleton, where the house ‘ale’ was twice the strength of the house ‘beer.’ The main exception to this custom seems to have been the term ‘October beer’ which described a very strong drink brewed in the autumn, apparently indistinguishable from ‘October ale.’” (p. 110)

“Strong October ale was so called because October was considered by most to be the best brewing month. Weather conditions were at their best and the new season’s malt was fresh. It was widely believed that beer kept better from an October rather than a March brew, which was probably true because newly-brewed ale was easily spoilt in warm weather; once it was three months old, it was slightly more tolerant of higher temperatures. This is not to say that strong ale was not brewed in March. Some households preferred the spring, and March beer is frequently mentioned by seventeenth-century writers, amongst them Gervase Markham. … This was the drink kept for special celebrations within the family. It was brewed at very high strength and intended for keeping at least a year before drinking.” (pp. 114-115)

This strong ale was called “beer” because it was brewed for keeping beer and thus more hops were used.

This country house October beer is what I believe they are referring to. So why in these references is it called “September beer”? My only thought is that these quotes are from the 17th century during the use of the Julian calendar in which September was slightly later than it is now. England switched to the Gregorian calendar in 1752. Dates were bumped back by roughly 10 days. Julian late September had the weather of Gregorian early October. So maybe in the 17th century they brewed September beer, but later on they brewed October beer. That’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

I will have to do a comparative search for “October” and “September” Brian, but one thing I have found is that original records especially from high status folk tend to be accurate for contemporary understanding. I would expect that the two terms would not be contemporaneous for the same item. But I love your calendar idea. That would be fabulous if the same thing is called by a different month one one side or the other of the change. October came twelve days earlier in 1752 and before that September would have been a bit more autumnal that the calendar would have us today believe.

The 1744 of The London and Country Brewer includes ways to brew October beer: https://archive.org/stream/londoncountrybre00lond#page/330/mode/2up/search/October