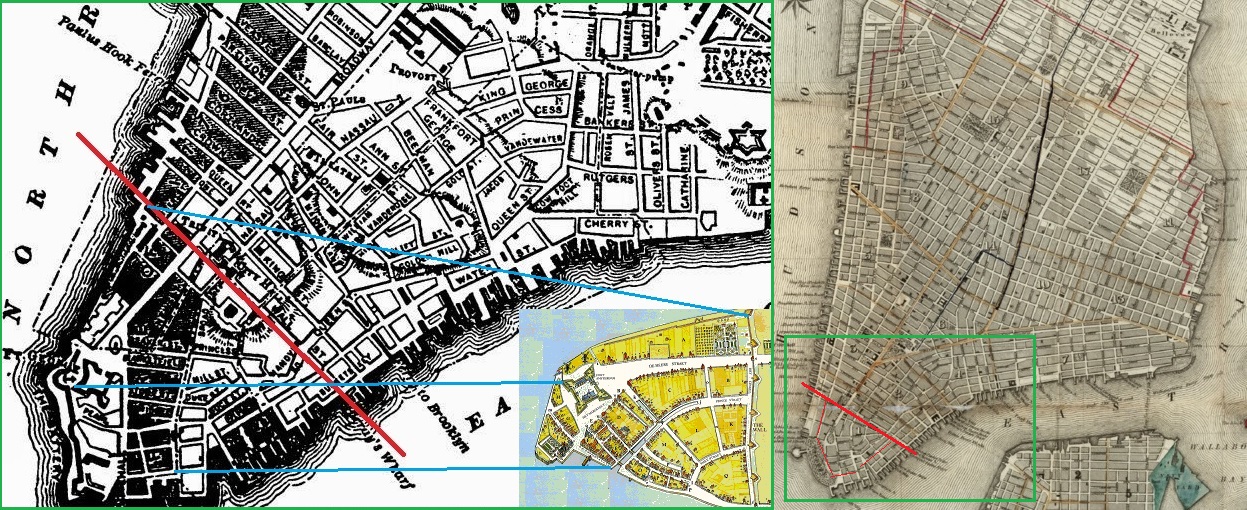

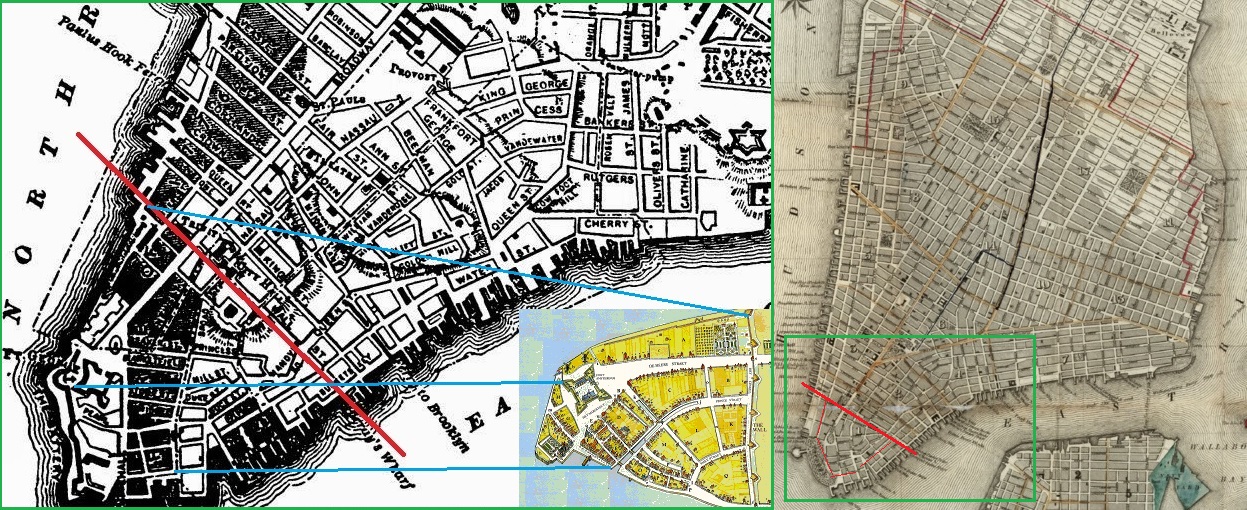

What a horrible diagram. It’s just a sketch but it’s a dog’s dinner. It illustrates the expansion of New York City from 1660, almost forty years into the life of the settlement, to 1839 just before the arrival of the fresh water in Lower Manhattan via the Croton Aqueduct. I offer you this to raise a general point. Breweries depend on the availability of resources. Not just hops, water, malt and yeast but also money and people and transportation and peace. The ability to run a brewery depends on the presence of generous stability. True then. True now. The bit of the diagram I am thinking about in particular in this post is the shift from the 1783 map at the left to the 1839 map to the right. What can these first decades of New York City in the early years of the newly independent republic tell us about the need for stability and resources? Plenty. Have a look at these two notices related to the brewer William D Faulkner:

What a horrible diagram. It’s just a sketch but it’s a dog’s dinner. It illustrates the expansion of New York City from 1660, almost forty years into the life of the settlement, to 1839 just before the arrival of the fresh water in Lower Manhattan via the Croton Aqueduct. I offer you this to raise a general point. Breweries depend on the availability of resources. Not just hops, water, malt and yeast but also money and people and transportation and peace. The ability to run a brewery depends on the presence of generous stability. True then. True now. The bit of the diagram I am thinking about in particular in this post is the shift from the 1783 map at the left to the 1839 map to the right. What can these first decades of New York City in the early years of the newly independent republic tell us about the need for stability and resources? Plenty. Have a look at these two notices related to the brewer William D Faulkner:

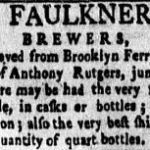

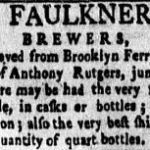

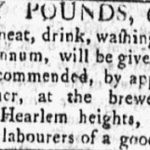

The ad to the left is from April 1770 while the one to the right is from March 1779. They describe Faulkner operating out of three breweries: the one at Brookland/Brooklyn Ferry, next to the Rutgers’ brewery on Maiden Lane and then on to the one at Mount Hope. In May 1768, brewing was a “new undertaking” to Faulkner. But in fairly short order, though either desperation or the entrepreneurial spirit, he is on the move. The Brookland Ferry brewery seems to have been a loser. Brewer after brewer have a go at running it from the 1760s to at least the 1790s. They each move on or quit. The Rutgers brewery on Maiden Lane seems to have a bit of a chequered career, too. As did the spruce beer brewery at Catherine Street. In the end, Faulkner leaves the lower end of the Hudson Valley altogether and ends his career in Albany by 1790.

There certainly could be a number of factors behind Faulkner’s moves but I am going to suggest that the search for clean water is one of them. One thing you notice from the maps and diagrams of Brooklyn Ferry of the time is that the area where the first buildings are located it just north of a high area, now Brooklyn Heights. Which hints there might have been originally a stream or creek along the path of the curving main street. After the area is built up, that stream would have been overwhelmed and would have lost its usefulness. Once that happens, the brewery finds itself sitting next to sea water with difficult access to water.

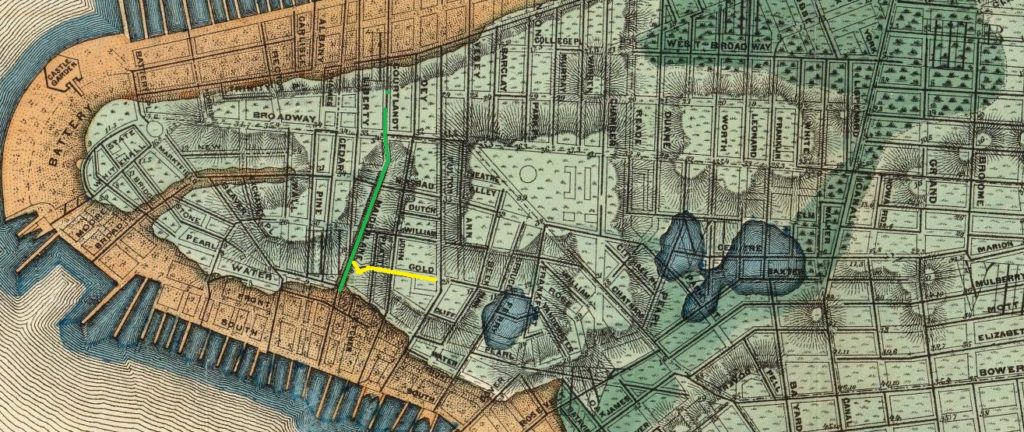

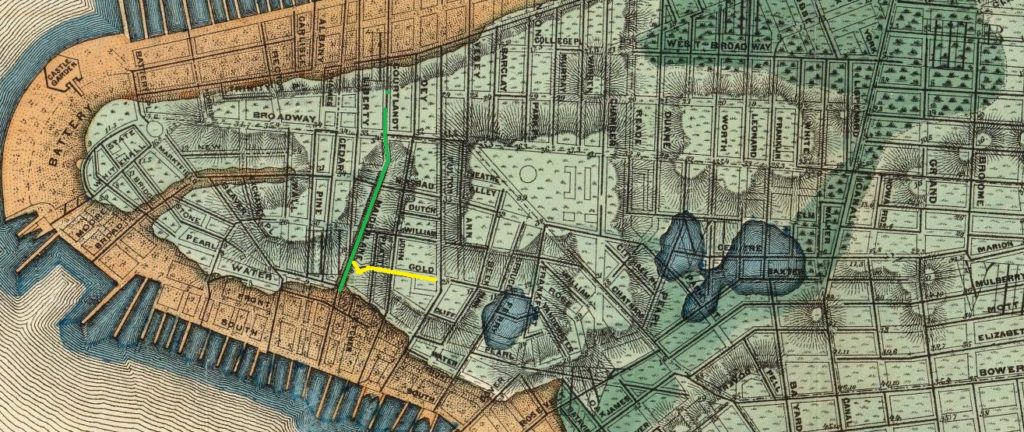

A similar story plays out more clearly with Rutger’s brewery. It’s located on Maiden Lane which, like at Brooklyn Ferry, is still visibly subject to road design decisions made hundreds of years ago. It was also a good address in 1790. Click on the thumbnail. That is a diagram of the Great Fire of 1776. I have shown Maiden Lane in green and Gold Street in yellow. They twist a bit. They still do today, 240 years later. Because they are based on watercourses. Metcef Eden locates his brewery up a little hill directly south of a twist on Gold Street. Have a look at this detail from the fabulous 1865 Viele map of New York.

A similar story plays out more clearly with Rutger’s brewery. It’s located on Maiden Lane which, like at Brooklyn Ferry, is still visibly subject to road design decisions made hundreds of years ago. It was also a good address in 1790. Click on the thumbnail. That is a diagram of the Great Fire of 1776. I have shown Maiden Lane in green and Gold Street in yellow. They twist a bit. They still do today, 240 years later. Because they are based on watercourses. Metcef Eden locates his brewery up a little hill directly south of a twist on Gold Street. Have a look at this detail from the fabulous 1865 Viele map of New York.

Click on it. The pale blue area is the original land mass, the light brown the filling-in of the river. You can see Maiden Lane again in green, Gold Street in yellow. Not only do they twist but they move from higher ground to lower ground. It’s a watershed. You will also see that lower Manhattan was originally very hilly. And, not very too far to the north, boggy. As shown in green. And, if you look at the ugly map way up top, it’s boggy exactly where the population growth occurs from the 1780s to 1840. To understand where was are going, however, we need to take a step back.

Harmenus Rutgers and his son Anthony Rutgers were very interested in water. While I think I need to go back and revisit the geneology but let’s just focus on two facts. First, in a court case, Rutgers v. Waddington, an 1784 ruling of the Mayor’s Court of New York City it states that Harmenus Rutgers bought the parcel on Maiden Lane in 1711 and started brewing at the end of that year. By 1784, the brewery is described as one of the most notable features of that part of the city. Second, in 1732 Anthony Rutgers obtained title to the swamp section of what was called the King’s Farm from the colonial government. If you look at the Bradford map of New York from 1731 or so, you see both Maiden Lane running east-west four blocks north of Wall Street and the King’s Farm to the north of that. Rutgers sets about creating a drain from the swamp which does two things. It regularizes and likely expands the waterway to the river and it formalizes what appears on maps as the Fresh Water Pond or Collect Pond.

Click on the thumbnail. That’s a detail of the 1776 Hinton which map has particularly good detail of the drains linking the pond to the river. In the mid-1700s, the Rutgers are clearly locating their interests with an eye to controlling good water. This is what the scene looked like in 1787. If you are familiar with the movie The Gangs of New York which is set, at its outset, in the Five Points district in the mid-1840s you are

Click on the thumbnail. That’s a detail of the 1776 Hinton which map has particularly good detail of the drains linking the pond to the river. In the mid-1700s, the Rutgers are clearly locating their interests with an eye to controlling good water. This is what the scene looked like in 1787. If you are familiar with the movie The Gangs of New York which is set, at its outset, in the Five Points district in the mid-1840s you are

familiar with the final years of what is likely the grimmest era of New York history. What you might not know is that the Five Point’s district was located upon the filled-in Collect Pond. It takes about fifty or sixty years for the area to go from well-ordered, drained cultivated fields to bleak hell hole of humanity. And during the transition a brewery plays a central role.

Click on the thumbnail to the left. It’s from the same map but shows this time what is to the south of the Fresh Water Pond. Tannery yards and a gun powder magazine. Even so, in the second half of the 1790s, the pond was still able to the portrayed as sitting in a parkland setting. There was even a little steamboat that took visitors on trips. It rapidly lost that character and, in 1805, in order to drain the now garbage-infested waters, the government widened Rutgers’ drains, opened a forty-foot wide canal that today is known as Canal Street and, by 1811, the City had completely filled Collect Pond. In The Old Merchants of New York City, Volume 5 by Walter Barrett published in 1885 it states:

Click on the thumbnail to the left. It’s from the same map but shows this time what is to the south of the Fresh Water Pond. Tannery yards and a gun powder magazine. Even so, in the second half of the 1790s, the pond was still able to the portrayed as sitting in a parkland setting. There was even a little steamboat that took visitors on trips. It rapidly lost that character and, in 1805, in order to drain the now garbage-infested waters, the government widened Rutgers’ drains, opened a forty-foot wide canal that today is known as Canal Street and, by 1811, the City had completely filled Collect Pond. In The Old Merchants of New York City, Volume 5 by Walter Barrett published in 1885 it states:

The house of Cadle & Stringham did a large mercantile business in this city for many years. The first of the Stringhams that I wot of, was Capt. Joseph Stringham, who commanded a vessel out of this port before the Revolutionary War, in 1774. After the war, in 1786, he settled down at 110 Smith (William) street, where I think he died. One son — I think Joseph — was a grocer in Queen street. No. 110. He was concerned with Janeway, under the firm of Stringham & Janeway, in a brewery in Magazine street (Pearl, from Centre to Broadway), as early as 1791.

Magazine Street at the time was that portion of what is now Pearl Street which was immediately south of the Fresh Water Pond. In an 1848 address to the St. Nicholas Society of the City of New York, the main businesses in the 1790s in this area are listed as (i) the pottery of Crolius, (ii) the furnace of McQueen, (iii) the tanneries of Brooks and Coulthard, (iv) the brewery of Janeway, (v) the starch and hair powder manufactory of N. Smith, and (vi) the rope-walk of the Schermerhorns.

George Janeway is listed in The Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York of 1862 as having been a brewer, Assistant Alderman, North Ward, 1784 to 1795 and Alderman, Sixth Ward, 1803 to 1804. Issac Coulthard advertised his tannery in the New York Packet on 7 December 1787. Interestingly, around October 1794, Coulthard was involved with the sale of a distillery near the Fresh Water Pond. In the late spring of 1795 his tannery burned down – a total loss. At the end of December 1796, Clouthard has erected a new brewery near the pond and started operations with his son. Not the same brewery as Janeway’s it would appear. Was that “the distillery” being sold a few years before?

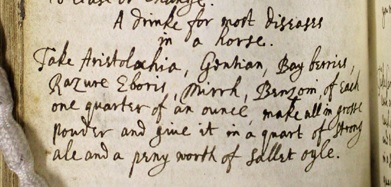

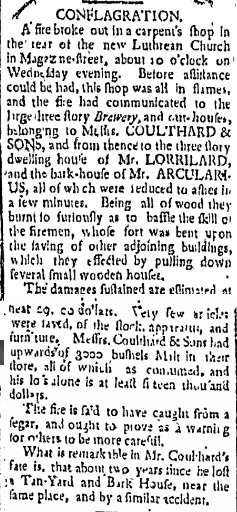

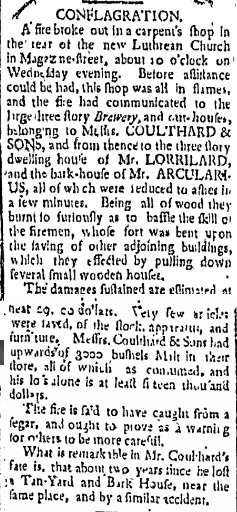

Anyway, the new brewery burned, too. I think they all burned, these old breweries. In the 1 July 1797 edition of Greenleaf’s New York Journal, right, it was reported that all the malt was lost and the whole business was a write off. An errant cigar at the nearby site of the new Lutheran Church apparently started it. He gets up and operating again as by July in 1806, his beers are being advertised as being on sale at the Porter and Punch-House of Henry Gird in Brooklyn. But he soon suffers a series of personal losses. His son dies in February 1807, his daughter-in-law dies in October 1810 and his daughter dies two months later – the latter two both of lingering illnesses. The visitations all are held on Cross Street, the heart of what becomes Five Points. And on 29 January 1812, the death of Isaac Coulthard himself is announced in the New York Gazette. The funeral procession started at Cross Street.

Anyway, the new brewery burned, too. I think they all burned, these old breweries. In the 1 July 1797 edition of Greenleaf’s New York Journal, right, it was reported that all the malt was lost and the whole business was a write off. An errant cigar at the nearby site of the new Lutheran Church apparently started it. He gets up and operating again as by July in 1806, his beers are being advertised as being on sale at the Porter and Punch-House of Henry Gird in Brooklyn. But he soon suffers a series of personal losses. His son dies in February 1807, his daughter-in-law dies in October 1810 and his daughter dies two months later – the latter two both of lingering illnesses. The visitations all are held on Cross Street, the heart of what becomes Five Points. And on 29 January 1812, the death of Isaac Coulthard himself is announced in the New York Gazette. The funeral procession started at Cross Street.

Over the course of his brewing career, the area his business operated out of changed from waterside parkland to a sewer. The pond has been drained and filled in. His son William Coulthard announced in September 1812 that he was carried on with the brewing but the neighbourhood was getting grim. And he had political ambitions, running for alderman for the sixth ward. He is named in a small notice placed for the brewery along with two partners selling double ale and porter in November 1820. One Joseph Barnes is operating the brewery in 1827 after William passed away in June 1822 at the young age of 56 – again of a lingering illness. Odd that so many of his immediate family died young and of lingering deaths. Was it the foul conditions of the neighbourhood? His house at 65 Cross Street next to the brewery is being rented out in 1831. Here is how the website Anthropology in Practice described the scene at that time:

…in 1805 or thereabouts, the city constructed a canal intended to drain the Collect into the Hudson and East Rivers. The canal soon also began to stink, and it was eventually moved underground as a sewer. Its former path was widened to become Canal Street. When this plan didn’t work as intended, city officials elected to raze bucolic Bunker Hill in 1811 and use the earth to fill in the pond to create housing for the growing population. As with any venture, marketing is important. The neighborhood that arose in this spot was named Paradise Square. Unfortunately, the land never fully settled. It was marshy, and mosquito-ridden, prone to flooding, and when buildings in the area began to sink—and the area began to smell—in the 1820s, the remaining wealthy residents fled the once desirable address. Immigrants and African Americans, seeking low cost housing as it was all they were able to afford, filled the area. By the 1830s, the neighborhood had settled into the Five Points, sporting a reputation as a dirty and dangerous place, which would thrive into the 20th century.

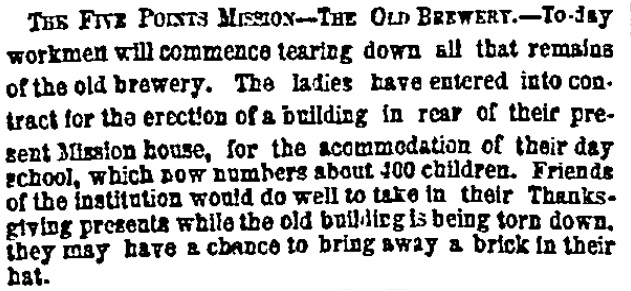

The Coulthard Brewery lives at least two more lives, first as a horrible slum and then as a mission house to the poor. The New York Evening Post of 23 February 1847 published an article on the suffering of Irish immigrants who found themselves living or laying dead and unassisted in Coulthard’s old brewery. An article in the New York Herald from January 1848 reports that near the brewery there were three or four killings a day in what was known as Murderers’ Alley. The basement of the brewery housed five families living on the floor and over one hundred hogs. In 1850, a report in the Schenectady Cabinet sets out that there were 32 families totaling 200 people living in the old brewery, none of whom were locally born adults. The end took a few more years but once The Ladies’ Home Missionary Society bought out the place, its days were numbered:

The Coulthard Brewery lives at least two more lives, first as a horrible slum and then as a mission house to the poor. The New York Evening Post of 23 February 1847 published an article on the suffering of Irish immigrants who found themselves living or laying dead and unassisted in Coulthard’s old brewery. An article in the New York Herald from January 1848 reports that near the brewery there were three or four killings a day in what was known as Murderers’ Alley. The basement of the brewery housed five families living on the floor and over one hundred hogs. In 1850, a report in the Schenectady Cabinet sets out that there were 32 families totaling 200 people living in the old brewery, none of whom were locally born adults. The end took a few more years but once The Ladies’ Home Missionary Society bought out the place, its days were numbered:

Note: “The labourers who wrecked the Old Brewery carried out sacks filled with human bones which they had found in the cellars and within the walls and night after night gangsters thronged the ruin to search for treasure which was rumoured to be buried there.”

++++++++++++Well, that was sordid. Next, I need to find out who else is brewing in New York from 1790 to 1840 and whether they had a bit better luck than the folk who lived around the Fresh Water Pond.

Anyway, the new brewery burned, too. I think they all burned, these old breweries. In the 1 July 1797 edition of Greenleaf’s New York Journal, right, it was reported that all the malt was lost and the whole business was a write off. An errant cigar at the nearby site of the new Lutheran Church apparently started it. He gets up and operating again as by July in 1806, his beers are being

Anyway, the new brewery burned, too. I think they all burned, these old breweries. In the 1 July 1797 edition of Greenleaf’s New York Journal, right, it was reported that all the malt was lost and the whole business was a write off. An errant cigar at the nearby site of the new Lutheran Church apparently started it. He gets up and operating again as by July in 1806, his beers are being