Writing about what is on other people’s beer blogs is a quick way to fill a day’s obligation to fill up one’s own sheet. But seeing as I have been trying to lead Ron Pattinson and his excellent library of brewing records into figuring out stuff that has piqued my idle sort of curiosity, I think it is well worth noting.

My questioning in these sour beer studies is triggered by one question – who the hell would drink sour beer over fresh? That question is packed with implications like “what is fresh?” and “what is sour?” and even “what is beer?” but it also is packed with the blindness of modernity, a fault that should be admitted from the outset as it is my question after all. It is reasonable to note that only recently that “fresh” was available to most people in the western world most of the time. For the most part food and drink were things that had intermediary storage periods by necessity of the annual cycles of nature. People were used to grain stores, bacon smoked above the fire, cheese with extra-tangy bits which would now see us deem the whole piece fit only for the garbage. So, too, people would have liked beer held for a time with a tang in addition to or instead of the fresh-made stuff.

But tang costs money. To hold beer long enough to gain a degree of souring, you need resources: enough space to store casks, enough money to buy the casks and even enough money not to sell the beer right away deferring the income to later. This is the thing that has niggled at the back of my mind in all this thinking about sourness and it brought me to thinking about cycles of beer storage. Beers like marzen or biere de garde are stored though a season once a year for an annual purpose whether it is to celebrate an event or fuel the harvest. And, like most of the present versions of the Trappist beers, these styles are recently framed, say, only since 1800.

So what gets a beer past its first anniversary? Ron points out one reason: “[i]f you have a good harvest one year, make beer with the surplus grain to be used in poor years. That seems to be the origin of Kriek: a way to preserve a glut of cherries.” And Martyn Cornell added a very useful comment to a recent thread at Ron’s about a very important record, Obadiah Poundage’s letter of 1760. Martyn kindly noted:

Alan, as Ron said, private brewers were storing their beers for a long time pretty soon after hops took off in England. William Harrison, a parson from Essex, writing in 1577, said the March beer served at noblemen’s tables “in their fixed and standing houses is commonly of a year old” and sometimes “of two years’ tunning or more.”

Luxury. Pure luxury. Only those who had the means to store could store. While it is as strange to us as a Victorian forcing house, those who could buy casks did as buying in bulk and cellaring was the only way really, as can be read in Julian Jeffs excellent book Sherry, that pre-mass marketed wines were acquired for the fitting out of the cellar of great house or (centuries fly by) an newly wealthy merchant – with the proper care and handling of the stored drink being part of the deal and expense and status. Martyn’s quote shows this applies to beer. With the industrial revolution, the earliest example of which industry is more than arguable brewing, references to the production and storage of beer by brokers for mass consumption seems to pop up in the records like Obadiah’s letter. Technology and more dispersed wealth make more general consumption of sour and tang possible, replacing the more modestly produced ales and brown beers that neighbourhood brewsters had been making for local consumption since Adam.

Keep in mind this is all sketchy, far too general and likely mostly wrong in that these are merely my own studies. But for now that is what I have come up with. And I would like to learn more about the available industrial archeology of, say, pre-1800 brewing. How much of production was stored for this quality if this quality cost more? And what part of the storage was stored for more that one annual cycle? Demand for sour had to be present such that the increased costs were overcome.

Any ideas where such stuff can be found? I should revisit Haydon, Unger, Hornsey and, of course, Cornell on the point. And pester Ron more. That’s likely the easiest thing to do

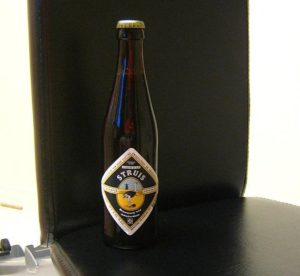

I have a sticker on my hand that says “$6.20” and on my desk I have a 330 ml bottle of Struis. In the US, that price gets the best part of a decent six pack of craft beer. In Ontario, it gets you half a six of Unibroue’s

I have a sticker on my hand that says “$6.20” and on my desk I have a 330 ml bottle of Struis. In the US, that price gets the best part of a decent six pack of craft beer. In Ontario, it gets you half a six of Unibroue’s