Ah, Utica Club. Craig brought Utica Club. He brought a few other beers. Beers that even came in caged cork topped bottles. But he brought Utica Club. It’s a funny beer. An old school macro lager made by a regional craft brewery. Is it hidden craft? Faux macro? Whatever it is, it’s five bucks for three litres at central NY gas stations. Summertime beer. Maybe even a cure for the summertime blues. Maybe. We talked over a pint or two before turning to a few more complex beers. Sweetish with a well placed jagged edge. Everything in its proper place. Nothing off or awkward. A beer for craft’s endtimes. Both pure and XX. According to the label. We talked of these endtimes. I blame Boak and Bailey, writing that non-derivative book that no one else will match. Takes the wind from the sails, didn’t it. So much for no one ever going beyond what’s gone before, been done before. Things get confused once those sorts of things get going. Not knowing your place. Can’t tell heterodox from orthodox. Hard to find which side of the map is up. Things go round and round. The saison driving north from Virginia or the Carolinas was wonderful after the cork popped. But so many are in a similar way, aren’t they.

Ah, Utica Club. Craig brought Utica Club. He brought a few other beers. Beers that even came in caged cork topped bottles. But he brought Utica Club. It’s a funny beer. An old school macro lager made by a regional craft brewery. Is it hidden craft? Faux macro? Whatever it is, it’s five bucks for three litres at central NY gas stations. Summertime beer. Maybe even a cure for the summertime blues. Maybe. We talked over a pint or two before turning to a few more complex beers. Sweetish with a well placed jagged edge. Everything in its proper place. Nothing off or awkward. A beer for craft’s endtimes. Both pure and XX. According to the label. We talked of these endtimes. I blame Boak and Bailey, writing that non-derivative book that no one else will match. Takes the wind from the sails, didn’t it. So much for no one ever going beyond what’s gone before, been done before. Things get confused once those sorts of things get going. Not knowing your place. Can’t tell heterodox from orthodox. Hard to find which side of the map is up. Things go round and round. The saison driving north from Virginia or the Carolinas was wonderful after the cork popped. But so many are in a similar way, aren’t they.

Month: July 2015

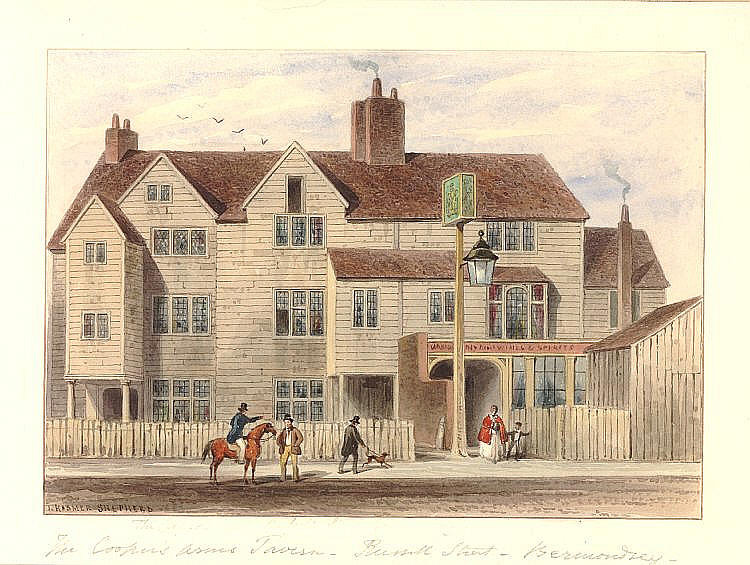

Clowes, Newbury and Maddox, Bermondsey, London, 1827

The brewery of Clowes, Newbury and Maddox sat on Stoney Lane in Bermondsey, London. The late Georgian artist John Chessell Buckler created a number of images from the district of Bermondsey. The watercolour of Clowes, Newbury and Maddox was painted in 1827. Charles Clowes, John Newbury and Erasmus Maddox that is. In 1868, the image was owned by the Corporation of London. I know nothing of Bermondsey other than what I read from Boak and Bailey or Stonch about the Bermondsey beer mile, something of last year’s model apparently. A place of rubbish-strewn industrial estates. Huge groups of lads getting pretty drunk, stag parties. Sounds fairly Georgian. Clowes, Newbury and Maddox were in operation in 1794. Charles Clowes was an admirable man, a lawyer turned brewer. He installed one of James Watt’s engines in 1796, even though he is reported to have refused the idea in 1785 after making inquiries. It is mentioned in a very interesting passage from 1805:

The brewery of Clowes, Newbury and Maddox sat on Stoney Lane in Bermondsey, London. The late Georgian artist John Chessell Buckler created a number of images from the district of Bermondsey. The watercolour of Clowes, Newbury and Maddox was painted in 1827. Charles Clowes, John Newbury and Erasmus Maddox that is. In 1868, the image was owned by the Corporation of London. I know nothing of Bermondsey other than what I read from Boak and Bailey or Stonch about the Bermondsey beer mile, something of last year’s model apparently. A place of rubbish-strewn industrial estates. Huge groups of lads getting pretty drunk, stag parties. Sounds fairly Georgian. Clowes, Newbury and Maddox were in operation in 1794. Charles Clowes was an admirable man, a lawyer turned brewer. He installed one of James Watt’s engines in 1796, even though he is reported to have refused the idea in 1785 after making inquiries. It is mentioned in a very interesting passage from 1805:

…the very capital malt distilleries at Vauxhall, Battersea, Wandsworth, and Kingston,. the large porter breweries of Messrs. Barclay, Clowes, Holcomb, &c. together with the infinity of pale beer breweries in the Borough of Southwark, and dispersed through every town and Tillage in the county, cannot be at a loss to account for the magnitude of the demand for this article.

Note. The infinity of pale beer breweries – not of households brewing pale beer – meeting the demand.

The brewery of Clowes, Newbury and Maddox seems to fit into Buckler’s interest in interesting and dilapidated structures from the previous century or before. He was an architect who was the son, brother and father of architects. The images are largely lifeless or rather at least without human participants. Their effect is sometimes present. The ruts in the road. Idle carts. His views illustrate scenes from the mapping I have been poring over. The Three Tuns public house on Jacob Street, Bermondsey to the left. The Duke’s Head Public House in Red Cross Street in the middle. The King’s Head Inn on the East Side of the High Street, Southwark to the right. The places Buckler took and interest in can be found on Greenwood’s Map of London from 1827 if you nose around a bit. The Duke’s Head lasted until at least 1874.

How I Actually Taste Beer According To Me

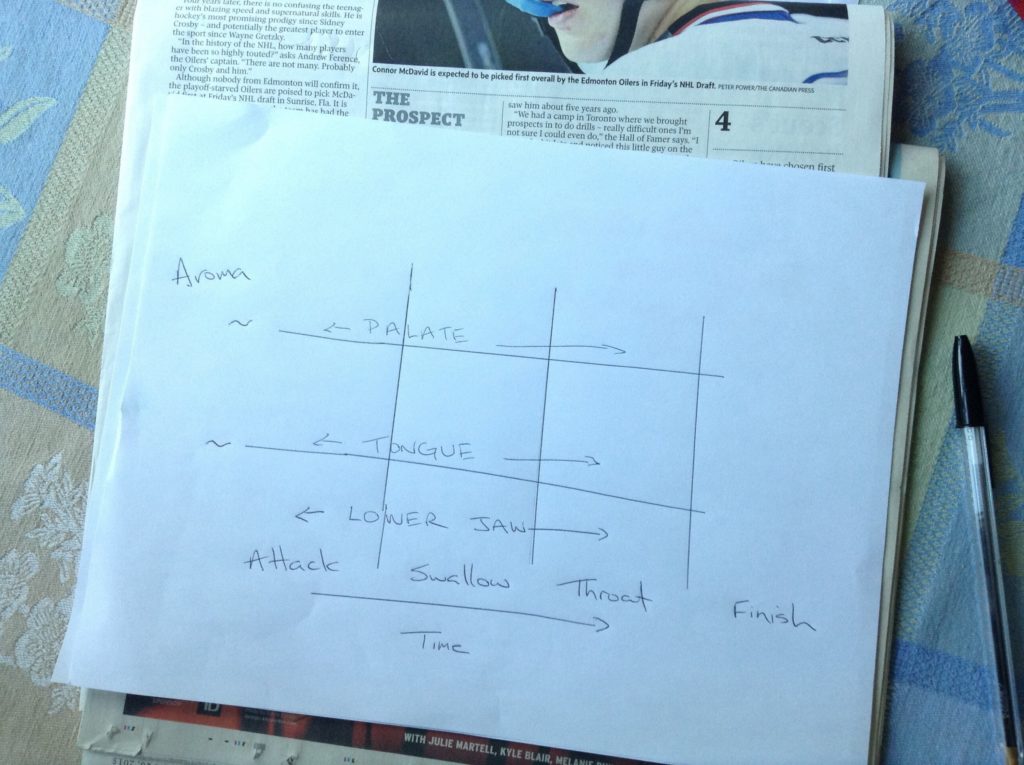

Once I used the phrase “the theatre of the mouth” and Stan liked the idea. Or maybe just the sound of the phrase. I was thinking about it today for some reason and realized that I had never described what I meant when I thought about this to myself. Well, the phrase itself places one in the seat, the only place that ultimately matters. No one can taste for you anymore than someone can attend a play for you. I was a playhouse usher for years so the analogy works for me.

Having now drawn the graph at dusk by the window, I wonder if it really works sitting there in 2-D. Nine squares through which the sensations move. Tic-tac-toe. I’ll have to think about this more, flavours and textures flitting in and out in order as the grid is traversed from left to right. Spaces between indicating selectivity and articulation. Do I fill it in with coloured pencils? Emoticons? My Little Pony stickers? Or by using it would it become less useful as a concept, a conceit?

Considering The Badness Of Beer In 1800s Britain

In all thy forms of Porter, Stingo, Stout,

Swipes, Double-X, Ale, Heavy, Out-and-out,

Most dear,

Hail! thou that mak’st man’s heart as big as Jove’s!

Of Ceres’ gifts the best!

That furnishest

A cure for all our griefs: a barm for all our—loaves!

Oh! Sir John Barleycorn, thou glorious Knight of

Malt-a!

May thy fame never alter!

Great Britain’s Bacchus! pardon all our failings,

And with thy ale ease all our ailings!

That’s the first bit of “Ode to Beer” from the Comic Almanack for 1837. What a jolly bauble. Exactly what we largely like to tell ourselves about the merry merry world of the past. Dickens without all the bad bits. The view from outside the Bermondsey¹ public house, as above, in 1854. As we all rush about finding older records to share about beer and brewing in, mainly, the English speaking world, I have wondered about the difference between the official record and the actual experience. By official, I don’t mean governmental or even sanitized so much as the accepted. The approved version. One of the biggest problems leading to the approved version is the love of drawing conclusions or, more honestly perhaps, the use of records to justify comfortable conclusions. We want things to be explicable but we want to be comforted. For authority to be correct we want it to align with out needs. It rarely does. But authorities won’t tell you that. Authority has another interest. Consider this passage in a book entitled England as Seen by an American Banker: Notes of a Pedestrian Tour by Claudius Buchanan Patten published in 1885:

I was at some pains to get at the following authentic statement of methods of beer adulteration. A member of London’s committee on sewers —an eminent scientist — puts forth the declaration that “It is well known that the publicans, almost without exception, reduce their liquors with water after they are received from the brewer. The proportion in which this is added to the beer at the better class of houses is nine gallons per puncheon, and in second-rate establishments the quantity of water is doubled. This must be compensated for by the addition of ingredients which give the appearance of strength, and a mixture is openly sold for the purpose. The composition of it varies in different cases, for each expert has his own particular nostrum. The chief ingredients, however, are a saccharine body, as foots and licorice to sweeten it; a bitter principle, as gentian, quassia, sumach, and terra japonica, to give astringency; a thickening material, as linseed, to give body; a coloring matter, as burnt sugar, to darken it; cocculus indicus, to give a false strength; and common salt, capsicum, copperas, and Dantzic spruce, to produce a head, as well as to impart certain refinements of flavor. In the case of ale, its apparent strength is restored with bitters and sugar-candy.”

Now, this is interesting. And not because all the horrible gak was added to beer back then as it is being again added to beer now. But because it includes the admission of wide spread watering down at the pub. Watered down poisonous gak. Which leads to the question of what people were really experiencing as they looked down into the murky depths of a pewter quart pot a century and a half ago. It makes me wonder it might mean for all those records Ron has dug out of public libraries and brewery attics. The badness of beer by these sorts of additives appears to have arisen after legal changes in 1862 as The British Farmer’s Magazine advised in 1875. But there are other issues, more to do with quantity than quality. This passage from The Farmer’s Magazine of 1800 is simply depressing:

There are some persons who do not drink malt liquor at all; most people of fortune and fashion drink it very sparingly; while great numbers of the lower orders, particularly coalheavers, anchor-smiths, porters, &c. drink it to great excess, even, it Is supposed, to the amount of five hundred, or one thousand gallons a year each. Upon the whole, I apprehend the quantity of malt liquor consumed in the county, would almost average a hundred gallons per head of all ages and conditions. One thousand gallons per annum, is nearly, on an average, about 14 bottles of ale or porter per day, and is almost equal to what is passed through many drains, made to carry off the superabundant moisture from the earth… upwards of three millions of money are expended by the labouring people, upon ale, porter, gin, and compounds, which is 25I. per family of that description of persons. If wages, on an average, be 12s per week, the amount per ann. is 32I. 4s. which leaves only 7I. 4s. for purchasing bread, butcher meat, vegetables, and clothes!

Holy frig. Perhaps we might take a moment to thank our lucky stars that we are not living when our great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandparents were scraping together their existence. When I tweeted the stats in that passage above, the good hearted Lars responded “I would guess a large proportion of that was small beer.” One does live in hope but, really, it’s unlikely isn’t it. The life of the industrial labourer and his family was simply horrible before the public health movement. In 1835, harvesting labourers required a gallon of beer every day for a month. In that same issue of The Farmer’s Magazine that that fact came from, there is a very interesting suggestion in an argument on why public houses were not going away despite their menace, why the labouring man had no choice:

…as to the temptation of company at the public-house or the beer-shop, would it not exist in precisely the same degree if the labourer had a cask of beer in his cellar brewed by himself, as if he had a cask purchased of the public brewer? If there were a disposition to avoid that temptation, and to drink his beer at home with his wife and family, what now prevents the labourer from purchasing a cask of beer and so consuming it? Nothing that would not equally apply to his purchasing malt and brewing his own beer. And if he had a cask, what security is there that his wife or children would not consume the greater part of it while he was absent at his daily labour? And would not he himself he likely to fall into the temptation of consuming it most improvidently either alone or with his companions?

We love to see things through rose coloured glasses. When we are not looking through amber coloured beer goggles ourselves. All but the first of the quotes and links are Georgian and pre-date temperance. When alcohol was so normal it was just a personal failing to let it affect your life as it washed over and through you. I honestly do not know what to make of it all. Have we simply forgotten the grim and bought into comforting fictions about the recent past? Accepted some sort of Jacksonian romance? My first reaction to it all is to praise the campaigners, to scribble a prohibition pamphlet – but then I remember that 1832 impromptu drinking party a traveler came upon in a cellar in Albany, NY:

…there was no brutal drunkenness nor insolence of any kind, although we were certainly accosted with sufficient freedom. After partaking of some capital strong ale and biscuits, we returned to our baggage apartment, and wrapping ourselves in greatcoats and cloaks…

The surprise of joy? Or a wallowing in the familiar? Or the land of liberty overlaid upon the event instead of the lives of those in the dark Satanic mills?

¹Yes, that one.

Three Mugs Of Beer For The Servant Girl

I’ve heard you. More tales of Cripplegate crime related to beer from the records of the Old Bailey. And why not? It’s good clean fun, in it? Let’s dissect the trial of Michael Martin and Hannah Farrington for grand larceny held on 15th October 1729. It starts out pretty clearly enough.

I’ve heard you. More tales of Cripplegate crime related to beer from the records of the Old Bailey. And why not? It’s good clean fun, in it? Let’s dissect the trial of Michael Martin and Hannah Farrington for grand larceny held on 15th October 1729. It starts out pretty clearly enough.

Michael Martin, and Hannah Farrington, of St. Giles’s Cripplegate were indicted for feloniously stealing two Gallons of strong Beer, value 2 s. the Property of John Ploughman, the 12th of May last.

Charged with a felony for two gallons of beer? What’s the prosecutor thinking?

It appear’d by the Evidence that the Prosecutor was a Brewer, and the Prisoner, Michael Martin, was his Servant…

Oh, that’s what’s going on. This is a private prosecution. The master, John Ploughman, has filed an information with the court against his own servant, Martin, for stealing the two gallons of beer. Breach of trust situation. The value is a bit of a side point if you think about it.

….that the Prosecutor having a Store-Cellar near Cripplegate , and Hannah Farrington being a Servant to a Customer of the Prosecutor’s, who dwelt hard-by this Store-Cellar…

Uh oh. Boy meets girl. Girl meets boy’s boss’s beer cellar. A story as old as love and beer cellars have been around.

…and having supplied the Prosecutor’s Servants with some Necessaries they wanted when at the Store-Cellar, the Prisoner, Michael Martin, or some other of the Prosecutor’s Servants, had at Times, in Return, given her three Mugs of Beer…

Had at times given her some beer! A bit imprecise for an alleged felony. Not only are the amounts of beer involved tiny but the dates of the supposed offences are sketchy. There must be more going on.

…and that the Prisoner Michael Martin , having given an Information to the Commissioners of the Excise of the Prosecutor’s using Molasses in his brewing Drink, did set on foot this Prosecution;

Ah ha! The truth will let itself be know, won’t it. Martin had ratted out his boss to the tax man for adulterating the beer and there by avoiding paying what was due. Malt tax was a pressing issue. A new tax in 1725 had led to riots in Scotland. Since 1697 In England, 6 pence was paid for every bushel of malt used in brewing. Folk were seeking ways around doing their duty. Bad folk were, that is. Folk like John Cheaterpants Ploughman. The case immediately begins to unravels rather quickly…

…giving the Drink not appearing in the Eye of the Law to be a Felony, and the Prosecution malicious, the Jury acquitted the Prisoners, and the Court granted them a Copy of their Indictment.

Freedom! Freeeeeedommmm! Well, no job and nothing but a piece of paper with the word acquitted on it but at least not transported or hanged by the neck until dead or anything. The latter prospect was cheerily and apparently popularly depicted in the background of that illustration up there showing the Old Bailey in 1735. Moral of the story? If you are going to cheat in 1725 cheat a bigger cheater who’s been cheating the Crown.