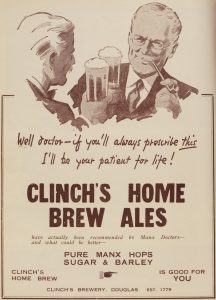

I have to say that imagining holidaying in any sense is a bit of a stretch for me and no doubt many others these days. Which tends to mean it is a good reason not to seek out strong drink but rather look elsewhere for meaning – like my choice this last few weeks: engaging in a prolonged and meaningful battle with the neighbourhood squirrels attacking my bird feeders. Think about it. Healthy outside-y lifestyle stuff getting out and setting up unstable and tall poles just out of a squirrel’s leap. Not quite what the doctor may have ordered on the Isle of Man between the wars as illustrated to the right but… is that really a doctor or the accounts manager of Clinch’s in disguise. And smoking! Dodgy looking moustache, that.

I have to say that imagining holidaying in any sense is a bit of a stretch for me and no doubt many others these days. Which tends to mean it is a good reason not to seek out strong drink but rather look elsewhere for meaning – like my choice this last few weeks: engaging in a prolonged and meaningful battle with the neighbourhood squirrels attacking my bird feeders. Think about it. Healthy outside-y lifestyle stuff getting out and setting up unstable and tall poles just out of a squirrel’s leap. Not quite what the doctor may have ordered on the Isle of Man between the wars as illustrated to the right but… is that really a doctor or the accounts manager of Clinch’s in disguise. And smoking! Dodgy looking moustache, that.

Victim of Math‘s starts us out on another week of pandemic laced news with a slight bit of economic upside news in the UK – or at least not a downside:

This is an interesting little nugget from the latest economic forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility… They expect alcohol duty revenue in 2020/21 to be *higher* than in 2019/20.

You may wish to roam the graphs and summaries of the associated Economic and Fiscal Outlook – November 2020 so here is the link to that. There’s this graph, too, that suggests in this economic downturn folk are turning to wine and spirits instead of beer. Are you?

Craft and shemomechama. Discuss.

Elsewhere and as it is to be expected, American big industrial beer is planning how to come out of the pandemic running. Beer & Beyond, the voice of MolsonCoors, Canada’s other secret infiltration force into the US economy right after Hollywood comedy movies, has asked the following about the marketplace:

With Americans heading into the holiday season, the beer industry is preparing for a winter fraught with uncertainty. A resurgent virus and ongoing recession are colliding with traditional times of elevated beer sales in both on- and off-premise venues. One thing is for certain: People are continuing to drink beer. The big questions are where are they buying it, and how?

The article goes on to state “…data from past recessions show, the beer industry tends to hold up relatively well during economic downturns…” which is true as far as it goes* but it will be interesting to see how this principle holds up where local policy driven pandemic triggering full on economic depressions are occurring in, for example, the non-masker alt-right parts of rural America.

Speaking of pandemic ridden landscapes of elsewhere, I fear I am not fully convinced by this week’s excellent article “I Am Gruit” but it is very gratifying that author Hollie Stephens did consult with one of Unger‘s texts:

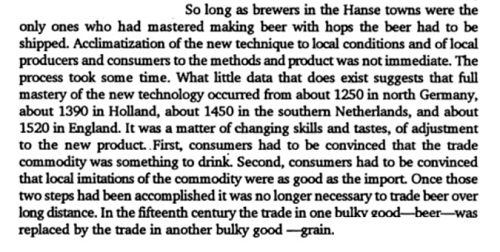

“The power to control to sale of gruit was in effect a right to levy a tax on beer production” writes Unger. Public figures who had been granted gruitrecht sought to extend their power throughout their domains. By the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, towns had taken over the taxation of gruit, handing the task of producing the gruit mixture over to a gruiter and ensuring that it was sold on to brewers at a fixed price.

It’s about the sense of scale. My reading of Unger’s work on gruit is that the scale of production (which went far beyond foraging) and resulting wealth it generated sustained the early modern… or the late medieval… era in the Low Countries and was only displaced more by the cannon of the Hanseatic League‘s hopped beer pushing trading ships more than anything. But otherwise a entirely helpful introduction fitted into such a short space. And a Steve Beauchesne sighting!

Also this week,** Ron wrote three blog posts about a drunken abusive vicar in mid-1940s Dogmersfleld in Hampshire, the Rev. Hugo Dominique de la Mothe. The name itself is a give away but here’s a summary:

The accusations brought under the Clergy Discipline Act of 1892, Section 2, were that between June, 1942, and June, 1944, the rector had been frequently drunk, had “resorted to taverns and tippling.” had been guilty of immorality in that on or about May, 1944. at Dogmersfleld, he was in such a drunken condition that he committed a nuisance in the presence of women, and that he made derogatory references to the husband of Mrs. Maggie Robinson, his servant.

Interesting that the matter held in Winchester Diocesan Consistory Court received such public notice. The cast of characters who show up as witnesses is gold.

In the now, the Tand Himself wrote this week about the new brewery in his home toun of Dumbarton, Scotland – even including a question and answer session with the owner thrown in for good measure:

The current production, as you’d expect, covers all the bases. One delight to this ex season ticket holder, is that the brewery produces the official beer of Dumbarton FC. This pleases me greatly as I remember all too well drinking in the Dumbarton FC Social Club – like the then football ground, but not the club – long gone. Then, we drank without a great deal of enthusiasm, beers from Drybroughs who had rather a monoclastic view of brewing, each beer being parti-gyled from a base beer which wasn’t great to start with. Mind you, we knew nothing of that then.

Less now but still somewhat tartaned, the history of Holsten Diät-Pils in the UK is the focus this week of an excellent post over at I Might Have A Glass of Beer:

In the 1980s so-called “premium lager” was the next big thing, as drinkers realised the watery draught lager nonsense they‘d been drinking wasn’t the real deal, and traded up to more fashionable bottled products. “More of the sugar turns to alcohol,” ran the tagline, alluding to strength in a way that got round the rules. The reference to the specially high attenuation was taken by drinkers to mean not so much “you can drink this if you’re diabetic”, but more “this will get you pisseder, faster”. In comparison to most British beers, Diät Pils was a alcoholic monster: 45% stronger than a 4% bitter and nearly twice as strong as mild or the draught ersatz “lager” people had been drinking before.

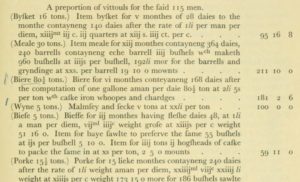

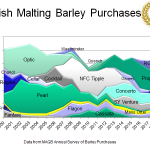

Malt. This image to my right caught my eye this week representing trends in the last 20 years of England’s malt barley deliveries. The variety of varieties is quite stunning as are the names. Somewhat more sensible in tone than what we have to put up with the recent namings in hops. Very much settled on the planet Earth.

Malt. This image to my right caught my eye this week representing trends in the last 20 years of England’s malt barley deliveries. The variety of varieties is quite stunning as are the names. Somewhat more sensible in tone than what we have to put up with the recent namings in hops. Very much settled on the planet Earth.

In further UK pubs and pandemic news, Stonch has found a sensible voice in Jonny Garrett:

…the REAL angle should be “pubs are SAFER than illegal gatherings at home”. They are controlled, clean, ventilated, so opening them could reduce home transmission. We need to campaign for that study.

This has been a line that Ontario’s Premier, Doug Ford, has been playing well. Best to be in well regulated settings. I still don’t go out that much but… you know… Elsewhere and to less effect, Pete B went wandering with some ideas on Scotch Eggs and alcohol absorption and governance models. Conspiracy abounds. But the £1,000 grant does seem a bit of the little and a bit of the too late, doesn’t it. Yet it’s in a combo of benefits we have on good word. So maybe it is…

Speaking of health… there was an excellent article in The Counter on the state of alcohol health disclaimers in the US and the role corporate lobbying plays to dumb it down with an interesting example from Canada’s north:

“I was surprised we were able to run it for [a month], honestly, before we got stopped,” said Stockwell, director of the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research and professor of psychology at the University of Victoria. “I was thinking that that was only because it was in the Yukon, out in the middle of nowhere. Nobody quite knew what was going on until the launch—that’s why we got away with it.”

Note: it is “…estimated that the cancer risk posed by drinking one bottle of wine a week was comparable to smoking five cigarettes for men and 10 for women in the same time span…” Excellently simple statement.

Finally, best beer blog interim research potentially becoming – but in no sense now – a fail yet… perhaps.

December, eh? Wasn’t quite expecting that. As you contemplate life’s passage once again, don’t forget to read your weekly updates from Boak and Bailey mostly every Saturday, plus more at the OCBG Podcast on Tuesdays (where this week they share a fear of teens and also speak of me, me, me!) and sometimes on a Friday posts at The Fizz as well. And sign up for Katie’s weekly newsletter, The Gulp, too. Plus the venerable Full Pint podcast. And Fermentation Radio with Emma Inch. There’s the AfroBeerChick podcast as well! And have a look at Brewsround and Cabin Fever. And Ben has his own podcast, Beer and Badword. And remember BeerEdge, too. Go!

*See that handy graph link above just a bit.

**Because, you know, this is a weekly update sort of thing…