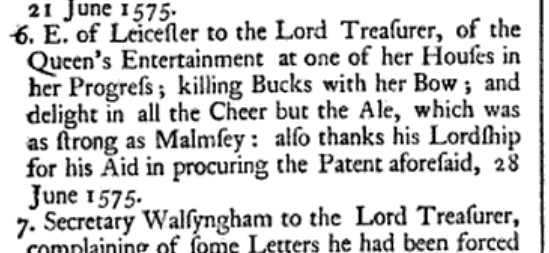

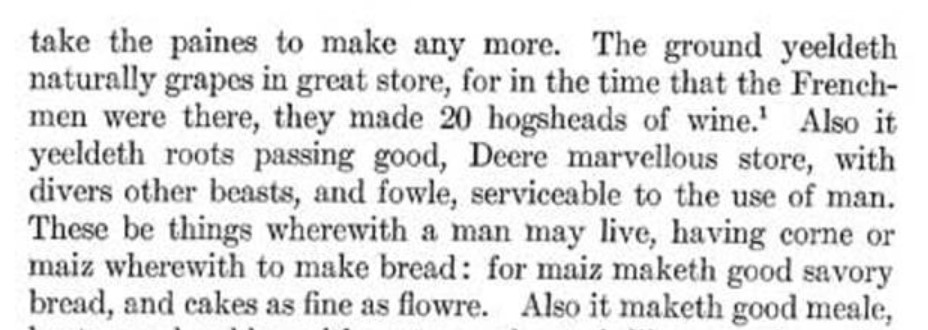

I have a thing for a beer I have never had. Double Double. As I understand it, this beer was made by recirculating perfectly good wort and rebrewing it through a new batch of malt. In the mid-1500s, it was a great bother for the nation, it even gets a mention in Shakespeare,* somewhat in open view. In 1560, Queen Elizabeth became directly involved as the supply of single beer was tightening. She ordered that brewers should brew each week “as much syngyl as doble beare and more.” Hornsey discusses a 1575 letter from the Earl of Leicester discussing a trip he took with Elizabeth, a summary of which from another source is noted above. When she wanted refreshment, she found her ale was as strong as Malmsey, heavy sweet strong Madiera wine. Not pleased.**

I have a thing for a beer I have never had. Double Double. As I understand it, this beer was made by recirculating perfectly good wort and rebrewing it through a new batch of malt. In the mid-1500s, it was a great bother for the nation, it even gets a mention in Shakespeare,* somewhat in open view. In 1560, Queen Elizabeth became directly involved as the supply of single beer was tightening. She ordered that brewers should brew each week “as much syngyl as doble beare and more.” Hornsey discusses a 1575 letter from the Earl of Leicester discussing a trip he took with Elizabeth, a summary of which from another source is noted above. When she wanted refreshment, she found her ale was as strong as Malmsey, heavy sweet strong Madiera wine. Not pleased.**

In the article “The London Lobbies in the Later Sixteenth Century” by Ian Archer, published in 1988 in The Historical Journal the resulting legal restrictions on brewing double double within and near to London was discussed:

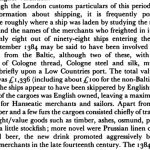

The parliamentary diarist Cromwell describes a bill in 1572 “restraining the bruing of double double ale or doble double beere within the Citie or iij miles thereof, and no beere to be sould above 4s. the barrel1 the strongest, and 2s. the single beere.”

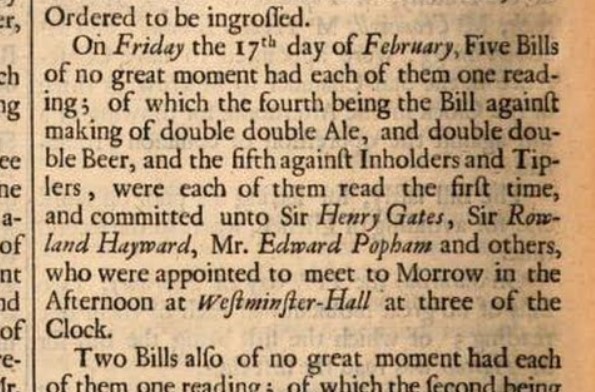

Archer explains that the goal of the regulation of ‘double double’ beer was supposed to ensure that the most intoxicating and expensive of beverages were not available to the poor, while also limiting the consumption of grain. To that, we might also add the waste of wood. England in the mid and later 1500s was not only facing speculation in malt was having a fuel crisis. Whole forests had been lost. Double double requires not only the loss of volumes of single ale and beer to the production process but also a second firing of fuel. The Common Council of the City of London had regulated double double for years before the statute of 1572 was considered. In 1575, as we can see above to the right, another general statute against the brewing of double double throughout all of England was before Parliament. Notice, too, that it was the brewing of both double double beer as well as double double ale that was being reined in by the law. The hopping of the beer in itself was not key to the question.

Archer explains that the goal of the regulation of ‘double double’ beer was supposed to ensure that the most intoxicating and expensive of beverages were not available to the poor, while also limiting the consumption of grain. To that, we might also add the waste of wood. England in the mid and later 1500s was not only facing speculation in malt was having a fuel crisis. Whole forests had been lost. Double double requires not only the loss of volumes of single ale and beer to the production process but also a second firing of fuel. The Common Council of the City of London had regulated double double for years before the statute of 1572 was considered. In 1575, as we can see above to the right, another general statute against the brewing of double double throughout all of England was before Parliament. Notice, too, that it was the brewing of both double double beer as well as double double ale that was being reined in by the law. The hopping of the beer in itself was not key to the question.

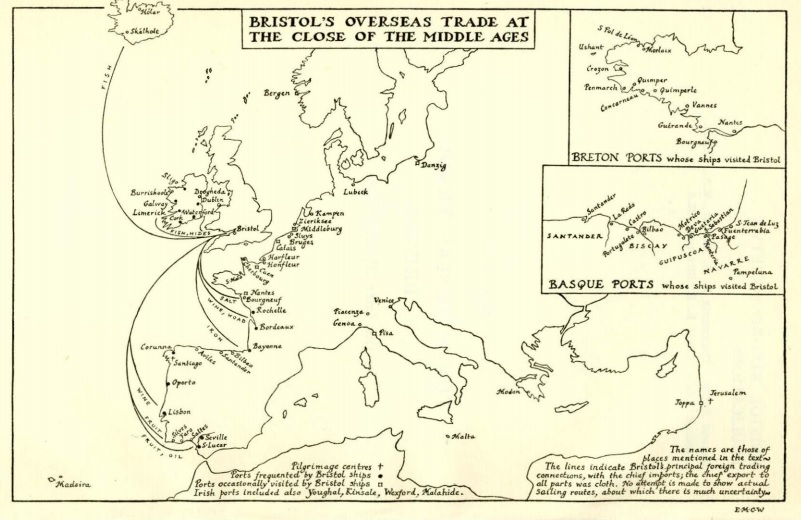

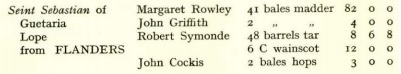

Beer brewers themselves were a bit suspect at this time. Strangers. Archer states that the Brewers’ Company was an unpopular group dominated by aliens and thought to be profiteering at the expense of the poor. As we saw a few weeks ago, “aliens” or “strangers” were foreign nationals who were subject to being recorded in a form of census. Yet, of the 1400s mood one can state that “stranger beer brewers found the Crown to be an ally throughout the fifteenth century because of their ability to supply beer to the military.” We also remember that Henry VIII created a beer brewing complex in 1515 at Portsmouth to supply the needs of his navy. Prior to that, the English navy had to buy beer from a group of 12 brewers in London. Probably including many alien beer brewers.

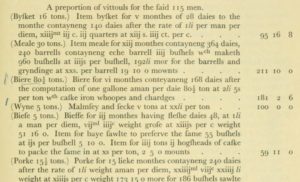

The role of hopped beer in military victuals continued. In 1547, the supplying of the Scottish town in England, Berwick, required a steady provision of beer by the tun. Likely in support of the army of Edward Seymour, maternal uncle of Edward VI, who upon the death of Henry VIII became Lord Protector. The expedition culminated in the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh in which 8,000 Scots were killed to 250 English. All too reminiscent of the outcome of that 1513 misadventure at Flodden when 10,000 Scots died and the English leader Lord Howard noted:

The Scots had a large army, and much ordnance, and plenty of victuals. Would not have believed that their beer was so good, had it not been tasted and viewed “by our folks to their great refreshing,” who had nothing to drink but water for three days.

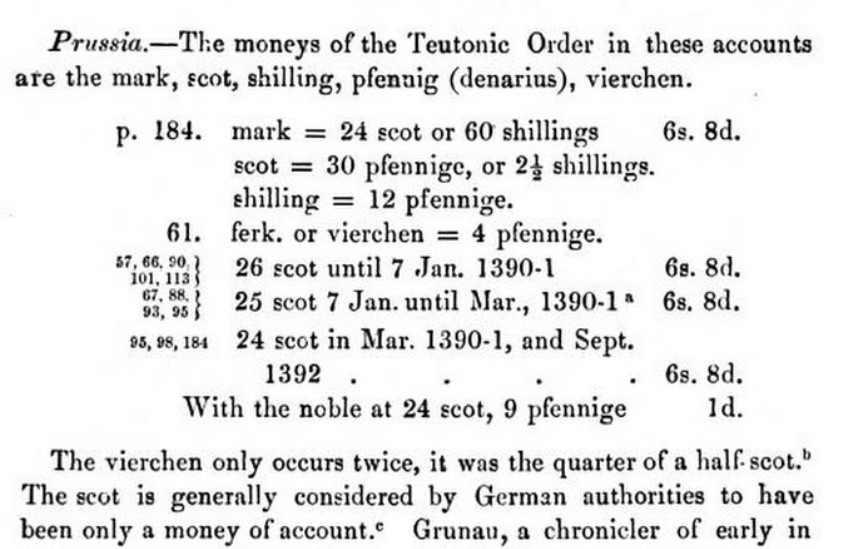

In a letter dated 29 January 1587, James Quarles, the surveyor general of victuals for the navy sets out his request to regularize the supply of provisions as England prepared to face the Spanish threat. He requests continued control of Her Majesty’s brewhouses, bakeshouses and storehouses and then sets the standard for a pottle of beer per seaman a day, at a price of 1 and 3/4 pence per day. Interestingly, he also notes that a tun of beer had increased in price by about 50% from the 1540s to the 1580s, from 18 shillings to 26 shillings 8 pence. As noted above, resources like fuel and malt were tightening.

While both the armies and navies of England depended on hopped beer, the civic beer brewers were not only suspect but, like the state run beer breweries of the later 1500s, they were busy. As we noted before, Kristen D. Burton in this 2013 article describes the scale of brewing being undertaken in the whole of the City of London during Tudor times:

The beer brewers of London established England’s capital city as the leading producer of beer throughout Europe by the end of the sixteenth century; a notable feat considering the late arrival of hopped beer to England. In 1574, London beer brewers produced 312,000 barrels of beer and by 1585 that had increased to 648,690 barrels…

Scale. So, it may be that beer brewing was more welcome or less of a concern to England in the middle of the 1400s than in the latter 1500s. Or perhaps it was too critical to the nation. This might go a bit against the existing narrative. Perhaps that is because it was first a fairly benign practice in harbour towns supplying the immigrant community. Hops being imported from the continent, just a few bales at a time as in 1480. One hundred years later, it has gone from being perhaps a local port town quirk to a key military asset to a danger to social order if let loose without controls on its supply, strength and price.

If that is all correct, one of the keys to the advancement of hopped ale was not consumer preference so much as military demand. Beer was stable where ale was transitory. Beer could be held on a ship or in preparation for a battle on the field. Ale needed constant production. It also needed rationing if that was the case. And Double Double, perhaps the sucker juice of its day, was no part of a rational rationing program.

Its last sighting was in Schenectady, New York in 1820 of all places and times. A few weeks ago, Craig unpacked the history of the brewers of that beer. They were men in transit during the great push west, the brewing of a Double Double apparently also transitory. Will I ever have one? I expect so. Perhaps Jeff is right and we are ripe for the wheel turning again. A massively malty beer would be just about right for a return to garage punk band brewing, shrugging off this era of discontent, this time of disco brewing of Franken-beers as foreign to ale as Malmsey.

*Conversely, Shakespeare gives “good double beer” a fairly respectful mention in Henry VI, Part 2, Scene III care of that unforgettable character, the Third Neighbour: “And here’s a pot of good double beer, neighbour: drink, and fear not your man.” Also note that it is beer, not ale. The play is set in around the last half of the 1440s so very little beer going about, one would have thought. Perhaps an anachronism? Or maybe a coy cultural reference to something lost to time.

**Not a wine without an unblemished past in court circles.

Up there, that is a detail from the

Up there, that is a detail from the