Why did Ontario have to make its own path to beerdom? Well, a war and a river for one thing. As we discussed yesterday, the land that is now Ontario was settled in 1783-84 by Loyalist refugees from New York state after the American Revolution. For the first five years, Kingston is a military town without civic government. Over the years that follow until about 1843, it is the leading town in the new British colonies of Upper Canada and then Canada. But the threat of war with nearby America hovers over it well into the 1860s. Kingston sits where the first Great Lake meets the St. Lawrence River which flows on past Montreal, past Quebec and out to the sea. For well over the first hundred miles of that flow, the south shore of the river is in US hands as are half of the islands. And that made shipping drink to that spot particularly difficult as this summary of a letter to the Governor of Canada dated 11 May 1783 suggests:

Why did Ontario have to make its own path to beerdom? Well, a war and a river for one thing. As we discussed yesterday, the land that is now Ontario was settled in 1783-84 by Loyalist refugees from New York state after the American Revolution. For the first five years, Kingston is a military town without civic government. Over the years that follow until about 1843, it is the leading town in the new British colonies of Upper Canada and then Canada. But the threat of war with nearby America hovers over it well into the 1860s. Kingston sits where the first Great Lake meets the St. Lawrence River which flows on past Montreal, past Quebec and out to the sea. For well over the first hundred miles of that flow, the south shore of the river is in US hands as are half of the islands. And that made shipping drink to that spot particularly difficult as this summary of a letter to the Governor of Canada dated 11 May 1783 suggests:

The want of rum; the Indians have been supplied a little more liberally than usual to keep them in good humour. The honourable and liberal conduct of Hamilton and Cartwright in lending rum, by which they must be considerable losers, only stipulating that a certain quantity of dry goods might be shipped for them at Carleton Island, to which he had agreed. The Indian officers that have resided at the Indian Villages for some time cannot be removed for fear of creating suspicions, but they will be discontinued as fast as circumstances permit, The Indians behave well, but he wishes Sir John Johnson would appear soon.

The Johnson clan, founders of Kingston, were an integrated family of Anglo-American’s and Mohawk. John Johnson’s step-mother was Molly Brant or Konwatsi’tsiaienni so the references to rum and its use describe a bond, not the disrespect and degradation that came in later generations. Almost thirty years before, in 1775 William Johnson, the elder, described his provisions of beer and their purpose in his accounts: on 6 June as ” 2 Barrels beer of Hend’k Fry for the Conajoharees to drink the Kings Health” and again on 22 July of the same year “To a Bull to the Mohawks + 3 Barrels of Beer for a War Dance at their Castle”. Beer and rum were part of the supply requested and required when you were making allies at the farthest end of the reach of the Empire. Because until 1777 – and really for some time later – the Johnsons and their well stocked booze stash are the western end of the British Empire except for a few thinly manned forts.

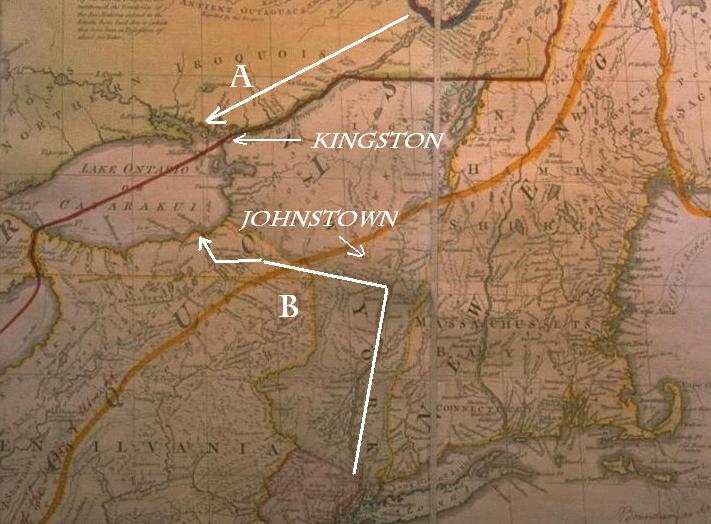

Which leads to a few observations. If you click on the map above, you will see that there is a route A and a route B to Lake Ontario, the navy filled buffer that protected the Loyalist settlers and later immigrants for their first four decades there. The St. Lawrence, a 112-gun first-rate wooden warship of the Royal Navy along with other cannon laden ships, was built at Kingston in 1814. It was bigger than any other ship in the fleet globally. But it could not reach the sea. Not by route A or route B. The St. Lawrence, route A, was filled with rapids that left the early inhabitants lake locked. Route B fell into US revolutionary hands with the fall of Johnstown in 1777 after thirty years of the upper reaches effectively under control of the one family, one man.

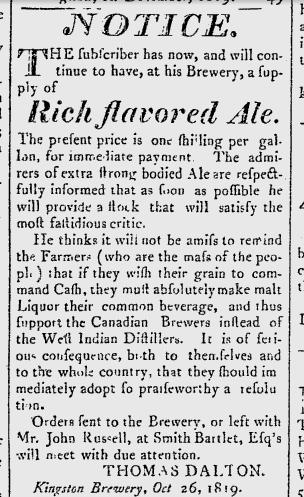

So, how to get beer to Kingston when one route is under constant risk of attack and the other is in enemy hands? Well, you don’t. You have to wait to grow crops and then you have to feed yourself, sell some off for cash and then sooner or later you get to the point that there is enough extra to make beer. Have a look at that ad we looked at yesterday placed in a Kingston newspaper in 1820 by the brewer Thoma Dalton. He is seeking both ale customers and malt suppliers in the local farming community as a means to overcome imported rum, as a means to create a local economy. The next year he is in Montreal with a trial shipment of 100 barrels of “Kingston ale” for public auction. He must have convinced the farmers of Kingston to do business.

So, how to get beer to Kingston when one route is under constant risk of attack and the other is in enemy hands? Well, you don’t. You have to wait to grow crops and then you have to feed yourself, sell some off for cash and then sooner or later you get to the point that there is enough extra to make beer. Have a look at that ad we looked at yesterday placed in a Kingston newspaper in 1820 by the brewer Thoma Dalton. He is seeking both ale customers and malt suppliers in the local farming community as a means to overcome imported rum, as a means to create a local economy. The next year he is in Montreal with a trial shipment of 100 barrels of “Kingston ale” for public auction. He must have convinced the farmers of Kingston to do business.

Over the next decade and a half Ontario continues to fill and local breweries are there. In 1836 there is a brewery for sale or rent in St. Catherines and another at the River Credit at the western end of Lake Ontario. Five years earlier, in 1831 there was a brewery even further to the west serving the 800 residents of the area of Guelph, currently home to micro turned national Sleeman as well as the craft brewers of the Wellington Brewery and the F+M Brewery.

So why did Ontario become a land of local beers made with local products sold to local people? There was really no other reasonable choice, no other good way to get your beer.