The other day I read one of the more interesting passages of beery thought that I had read in some time. It’s from a response to a post at Jeff’s Beervana about the wonky less than linear history of beer styles:

While it’s entirely possible that malt bills and hopping rates of many of craft brewing’s “new” styles might have had occurrences in the past for which records are poor, incomplete or just plain lost, historically brewers could NOT have brewed beers that we’d be able to directly compare to some of the popular craft brewing styles today. Why? Ingredients. There are simply varieties of malts and hops available to brewers today that are, in a word, new. These newer varieties are creating flavor profiles that weren’t really available to brewers of yore. Hell, the venerable Cascade hop only came into usage in the 1960’s I believe. Combinations of malt and hops in the way they are used today, but using instead the varieties (including malting techniques) of, say, a hundred years ago, would have yielded beers that are so dramatically different that we’d say that they were different styles. IPA is a simple example. One of the key characteristics of the “American IPA” is not just how much hops are used, but the fact that the bitterness, flavor and aromatic profile is centered around newer American varieties of hops.

I like this. It admits that the fashionable brewer is dependent on the new ideas of the maltster and the hop grower. And on new ways of doing things. But we know also the Albany Ale project has proven the opposite is quite true as well. Ingredients (aka stuff) which once were are no more. We have no idea what Cluster was like in 1838 any more than we know what hop will govern in 2038. We live on a river of time where the shock of the new is nothing compared to the disappearance of the past. And, if that all is true, are the style guidelines – like those updated as announced in a press release from the Brewers Association today – really as heinous as we might all quite comfortable suggest to each other? Or do they just express the today we happen to find ourselves facing? Put it this way – if new forms of ingredients and new ways of brewing should come into the market, why shouldn’t new names and concepts of classes be added to describe them as these are woven into our beer?

Let me illustrate the point.with an analogy to the strength of pale ales. The other day when I was doing my drinks free drinks dialogue I discussed how the range was both expanding and filling in. I suggested that I now needed a new word to be coined for me to describe US pale ales between 5.6%-ish and 7.4% or so. Something between a pale and an IPA that might itself be from 7.5% to about 8.5% where the double IPA may start to make merry up on up to 10% before they yield in turn to imperial IPAs. None of that really makes sense when compared to brewing heritage or even recent trendy trends… but if I am having a 6.5% brew, I have no illusions that I am in league with either a 4.9% or a 8%. I want to have words to describe this difference.

If that is the case, is difference based not on strength but on a change in methods or a novel ingredient so wrong? We all know that these style guides are not ultimately important let alone critical to understanding and appreciating beer. We admit that. But are they wrong? Consider the idea of “field beer” at page 30 of the new guidelines for example. Clearly deciding to disassociate itself from the downside of vegetable, it is a splintering off from fruit beer and herb beer. Fern ale might fit in here. Sure we would need someone to pick up and brew the style last described in 1668 but if it not only were brewed but then became the pervasive fashion totally replacing retro light lagers as the preferred drink for the hipsters of 2038 – why not describe it as its own separate style?

[Original comments…]

Chris – February 8, 2012 9:30 PM

I think it’s about finding that balance between meaningful and utterly useless. New ingredients, techniques and methods will yield beers that taste different than beers of the past have. I think it’s quite right to categorize accordingly, but it gets tricky. You don’t want to rigidly conform or force a beer into an already-existing beer style for the sake of organization, and at the same time you don’t want to subdivide so many times to the extent that the resulting styles are meaningless or useless. I think we’ve yet to locate that balancing point, is all.

Joe Stange – February 9, 2012 11:35 AM

http://www.thirstypilgrim.com

So there is something new under the sun, after all.

Will – February 9, 2012 12:41 PM

http://perfectpint.blogspot.com/

Albany Ale… has everyone else given up on that? I’m still trying to get access to some brewing logs of the period, though would it be safe to assume that Albany Ale is just another name for Burton ale; or some type of strong-cream ale? I got the ingredients to resurrect this beer, including the original hops, though I’m still looking for that elusive recipe.

Alan – February 9, 2012 1:43 PM

Will – not safe at all. There is plenty of reason to consider it a stand alone that was not sufficiently recorded. The malt you have and the yeast you have and the hops you have are likely all wrong simply because they are lost. I might be wrong but that is the point. No record, not recipe, no style left to recall.

Joe: all things old are new again… especially if I can get some fern malt

Gary Gillman – February 9, 2012 4:17 PM

What I find interesting though are the many connections between historical and modern brewing. E.g. I was just reading in Frank Faulkner’s brewing text from the late 1800’s where he contrasts London and Dublin porter. He states the Dublin style was a mix of matured stout, mild (new) stout that was “clean”, and “heading” or half-fermented beer added to condition the beer (to produce the thick head that is ancestor to today`s nitro version). For London Porter, he states it is practically all mild with no “acidity”. I can get a good idea from this what the beers were like, when you add to it that brown malt of the day was kilned with wood fires or a mix of coke and wood. (Contemporary malting manuals make this clear).

I’ve had many beers today which fall into these various categories. Cascade is new to be sure (from 1972 IIRC), but 1800’s accounts in England complain that American hops have a taste of “pine wood” or “blackcurrant“. A piney taste is characteristic of many U.S. beers today.

I agree that we can never know for sure, but I feel you can often infer what beers were like from extensive reading in period s and (to me) often they sound similar to various kinds of craft beers available today. There is always a limit to be sure. Did chocolate cran-apple brown ale exist in 1870? Maybe not, but then too given the 1000’s of beers made in the beer-brewing countries then, perhaps something like that was a local specialty in Vermont or Kent, England, who knows… There were certainly cherry ales in England according to the late historian and food writer Dorothy Hartley. It’s not such a hop skip to what sounds like a modern concoction if, say, some mixed it with porter.

Gary

Gary Gillman – February 9, 2012 4:35 PM

Just another example, Alan. I was looking at online sources to find out what people think blackcurrant tastes like. One description said it was like a combination of a flowery and musky taste. I’ve had APAs (lots) that taste like that! We have modern varieties of malt and hops, but I wonder if there are imperishable characteristics of soils – terroir in a word – that impart certain qualities that don’t change despite the genomic make-up. Same thing for hops in England. Goldings have existed for hundreds of years under the same name, I’d think it reasonable that they taste pretty much the same now as in 1850 (or close enough).

Then too historical recreations of beers are increasingly available, and these, while often (not always) excellent, often resemble craft beers I had in numerous places.

But we will never know for sure and I offer all these thoughts with that acknowledgment.

Gary

Will – February 9, 2012 9:04 PM

Good points Gary. Beer is not so ethereal that the ingredients used in its production just up and disappear when someone stops brewing a particular style. Malt and hops do change over time, though the basic properties/flavors remain the same and can be replicated to a sufficient degree. I am pretty sure that the english cluster and humphries hops I have in my freezer are going to be similar tasting to the same hop varieties that were growing in the same field, 100 years ago. And actually, black currant is a pretty good description of their flavor. They are a bit “catty” too in larger amounts.

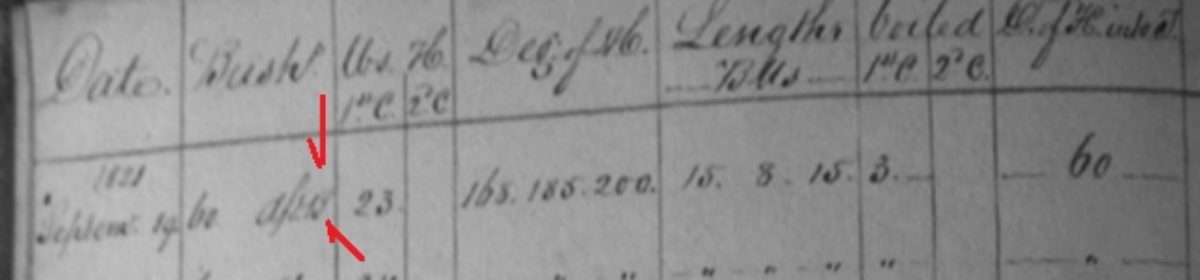

How then can we say something like Albany ale is lost? We know the ingredients they would have used to make it – pale, amber, or brown malts, or a combination thereof – maybe some wheat, though unlikely, and local hops. And unless they were dosing the beer with so much salt that it made it taste so different than anything brewed before it, again unlikely, we should be able to make an educated guess of what the beer was like. Until we find the brewing logs, we don’t know for sure, but “lost”… I’m not buying that.

Alan – February 9, 2012 10:05 PM

I am not disagreeing with you, Will, as by “lost” I do not mean lost forever. More like the Amazing Grace of Beer. Maybe these are “hidden” styles. I do want my fern ale.

Plus, there were clearly many brewers making strong pale ale with local ingredients in Albany so there is reasonable argument for a range of flavours. Wheat is actually more than likely given references in the 1700s but you are right – there is a hope and it sound like your hope is stronger than mine at the moment.