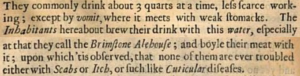

That’s my new favorite quote about sulfurous brewing waters from around Burton. It’s from The Natural History of Staffordshire from 1686 by Robert Plot. It’s slightly misleading as the beer was brewed as a local health tonic but I love that it was available at the Brimstone Alehouse. I want a black t-shirt from that place. What’s that, you say? What’s with another 1600s blog post? Where is this coming from? Well, Martyn mentioned it in a comment but nowhere near as well as in the email he sent that started…

Curse you, Alan, for sending me on a winding chase across many volumes … and proving to me again that you can never trust any other fecker’s references, you always have to confirm them yourself. Peter Mathias’s reference in The Brewing Industry in England (p150) to Burton ale allegedly first being sold at the Peacock in London in 1623 appears to be completely wrong:

Secondary sources. They always let you down.

Where were we? Burton ale. From Staffordshire. A joy and comfort to Britain from, let’s say, 1750 to 1950. Where the particular beers are brewed from particular waters have extremely sulfurous water – though, to be fair, maybe a bit less than the water found at the Brimstone Alehouse. Yet, is a beer being good for scab or itch enough to get it a commercial market in London in the 1600s? I don’t think so. Mathias shouldn’t have been trusted. It’s certainly not something perhaps to travel for. Don’t get me wrong. There was a road from nearish Derby to London in the era, as mapping from 1675 by John Ogilby shows. But in 1675 are you really going to seek out the ales of the area unless you are, you know, (i) scabby and itchy and (ii) in the know? Likely not. And if you are the brewer do you send it off by ox cart to a urban world you’ve never seen down roads you couldn’t possibly trust? Likely not. Why? We have to obey the chronology. Not only was the Trent only made navigable in 1712 or so but that other big transportation innovation, the turnpike, only shows up a few years later. Practically speaking, reasonably good roads are one or two generations away. The Staffordshire County government has an exceedingly interesting and exceedingly lengthy report on the turnpike markers of the area which states:

Throughout the early years of the 18th century parishes were complaining that the upkeep of the roads through them was impossible due to the increased traffic. This is especially true of Staffordshire: so many through routes were being used, the travellers along them having no business with the parishes concerned. Steps were taken to remedy the situation with the increasing turnpiking of major routes, effectively privatising the main roads. Turnpike Trustees were appointed to oversee the collection of tolls, which they used in order to maintain the highways, any theoretical profit returning to the trustees.

Being on the cusp of greatness does not make one great. Safe commercial connections for moving beer in the medium future does not make it safe in the present. So, it may well be those sitting around the bar at the Brimstone Alehouse in 1686 lived long enough to see the ales of Burton on Trent be recognized for being something bigger than a balm for the scab and itch. But in that year they may have been among the few enjoying the particular delights of the region’s sulfurous brew.

Does The Natural History of Staffordshire written at the time help with the question? To be fair or even just honest, Plot’s book is a survey of the natural and economic characteristics of the county, a scientific study based largely on the four humours. It’s not a gazetteer of commerce like you might find in the 1800s. Trades are referenced in connection to the considerations of the air, water and soils. Burton itself gets passing mention and mainly what is mentioned is the bridge. Brewing is not a focus. The word “malt” only shows up once. Yet beer and ale are mentioned. We are told that they have an Art in the county of making good ale.* Folk are described as paying respect to certain wells on the saint’s days “whose name the well bore, diverting themselves with cakes and ale, and a little music and dancing.” One noted human oddity of the county, however, was a person who “drinks neither wine, ale or beer.” Another, a baby who lived only three days even though it “took milk and beer freely enough.” And, perhaps crucially, the setting up of a cheese factory by Londoners is described in some detail as is another group making salt by evaporation – including using in one process “the strongest and stalest ale they can get” to make the crystals set as desired.

Robert Plot describes the Staffordshire he visited in pastoral tones. If there was a trade to London in beer like there was in cheese he might be expected to have mentioned it. But he didn’t. Coming 26 years before the navigation improvements made to the river Trent and many more before the improvement of the roads it’s most likely that the markets did not yet exist for brewing at scale for export beyond the local market. It didn’t not yet sit even in the shadow of other noted brewing centres like Hull and Margate. One record I do not have and which may not exist would be helpful. The excise duties on beer and ale introduced in the 1660s, which came into being with the Restoration of Charles II to his thrown might be quite helpful if they drilled down into county by county assessment, town by town. It would help sort out where the brewing was going on by providing a contemporary primary record. For now, a book like Plot’s is the best we have. Certainly, it seems, better than Peter Mathias’s… at least on this point. We only know what the records tell us so far.