I’ve been trying to figure out how to catch up notes on some of the larger New York breweries* in the 1790s and early years of the new modern nineteenth century. It’s a time of transition and not just in the sense of the changing of the guard. The post-war political and economic confusion was well on its way to leveling out. One factor that was helping were the Napoleonic Wars and Europe’s continuing disruptions. There was a market for grain on the continent and Britain had a bigger enemy to deal with. Still, there was also a changing of the guard. Even though many of the big brewing interests in both Albany and NYC backed the winners, they did not stay in brewing for very many decades after peace broke out.

Among many things, one interesting aspect for me is how repetitive the pattern is in the beer industry. Beer is an easy entry trade that, when done well, eventually offers wealth and perhaps even political power. As we see today in the big craft sell off, it can take time but what doesn’t? Folk with the myopic interest in whatever the PR guy or craft brewery owner is handing out as a story may not notice but brewing is a great way to shift one’s economic class upwards. A business for the ambitious to enter then later leave. Perhaps a summary post will help illustrate what is arguably happening at the turn of the nineteenth century and how similar it might seem to today. Think of it just like a weekly bullet point round up but for a period of time lasting just about the best part of a decade about two centuries ago.

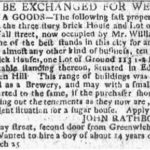

First, let’s consider the Eden brewery of Gold Street in NYC. Last November, I posted about the brewery of Medcef Eden** on Gold Street just off Maiden Lane. When last we met George Appleby had taken over the place in 1791. Medcef is too prosperous to bother running the place himself. The brewery is located opposite the First Baptist Church on the corner of John and Gold, a bit of a highland location. Appleby is still there in October 1792 brewing his ship’s beer and spruce beer even though he is no longer on the waterfront. On 16 November 1795, right below the report on the price of pork, the Albany Gazette reported the death of George Appleby, remembering his years with former partner Mr. Matlack. In the 19 October 1797 edition of the New York Gazette Eden is selling off his kettles as well as hair cloth, used to moderate the malting and kilning process. The sale is secondary to his reward for the return of “stolen” slaves. Not runaways. Stolen. Medcef Eden Sr. dies in September 1798 and leaves his estate to three executors: Joseph Eden, Medcef Eden Jr and Martha Eden. The site of the brewery was also done by 1802. A notice in the New York Daily Advertiser from 27 March of that year – as shown under that thumbnail – indicated the site had been formerly occupied as a brewery but would take a some level of conversion to revert back to that use. The kids ain’t interested. And arguments over the will, due to the later huge value of his accumulated Manhattan lands, go on for decades. I suspect you will see this sort of thing when hold out craft like Stone gets into the next generation of ownership.

First, let’s consider the Eden brewery of Gold Street in NYC. Last November, I posted about the brewery of Medcef Eden** on Gold Street just off Maiden Lane. When last we met George Appleby had taken over the place in 1791. Medcef is too prosperous to bother running the place himself. The brewery is located opposite the First Baptist Church on the corner of John and Gold, a bit of a highland location. Appleby is still there in October 1792 brewing his ship’s beer and spruce beer even though he is no longer on the waterfront. On 16 November 1795, right below the report on the price of pork, the Albany Gazette reported the death of George Appleby, remembering his years with former partner Mr. Matlack. In the 19 October 1797 edition of the New York Gazette Eden is selling off his kettles as well as hair cloth, used to moderate the malting and kilning process. The sale is secondary to his reward for the return of “stolen” slaves. Not runaways. Stolen. Medcef Eden Sr. dies in September 1798 and leaves his estate to three executors: Joseph Eden, Medcef Eden Jr and Martha Eden. The site of the brewery was also done by 1802. A notice in the New York Daily Advertiser from 27 March of that year – as shown under that thumbnail – indicated the site had been formerly occupied as a brewery but would take a some level of conversion to revert back to that use. The kids ain’t interested. And arguments over the will, due to the later huge value of his accumulated Manhattan lands, go on for decades. I suspect you will see this sort of thing when hold out craft like Stone gets into the next generation of ownership.

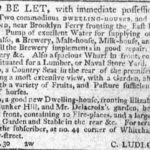

The Brooklyn Ferry Brewery tells a different story. One of grit, determination and successive failure. Almost insistent failure. In January, I wrote about the brewery at Brooklyn Ferry from the mid-1760s to 1795. At that point, the lands and wharf which had been built up by Isaac Horsfield and his sons were being leased out by one Cary Ludlow. The actual brewery was described as Mr. Sing’s. A tenant. Maybe a sub-tenant. In the Christmas Day 1795 edition of the New York Gazette placed R.W Maddock and Co. as brewers on site with cellars for their ale and beer being kept in lower Manhattan. Just fourteen months later in February 1797, the partnership with Mr. William Sing and another behind the “Co.” dissolves and early that summer, Roger Worthington Maddock is selling off the remainder of the term of his lease and all his equipment. The curse of Brooklyn Ferry continues. Ludlow gives notice of the opportunity to buy the brewery and associated lands again in 1801 as well as in 1803, shown above, with a great description of the range of facilities on the site: brewery, malt house, milk house, kiln, wharf as well as a water pump to supply ships at dock. Still, it was cursed. Lesson? The brewery, the brewery owner and the brewers are very different classes of thing. Pay attention today to how many craft “brewers” never did the actual work of brewing.

The Brooklyn Ferry Brewery tells a different story. One of grit, determination and successive failure. Almost insistent failure. In January, I wrote about the brewery at Brooklyn Ferry from the mid-1760s to 1795. At that point, the lands and wharf which had been built up by Isaac Horsfield and his sons were being leased out by one Cary Ludlow. The actual brewery was described as Mr. Sing’s. A tenant. Maybe a sub-tenant. In the Christmas Day 1795 edition of the New York Gazette placed R.W Maddock and Co. as brewers on site with cellars for their ale and beer being kept in lower Manhattan. Just fourteen months later in February 1797, the partnership with Mr. William Sing and another behind the “Co.” dissolves and early that summer, Roger Worthington Maddock is selling off the remainder of the term of his lease and all his equipment. The curse of Brooklyn Ferry continues. Ludlow gives notice of the opportunity to buy the brewery and associated lands again in 1801 as well as in 1803, shown above, with a great description of the range of facilities on the site: brewery, malt house, milk house, kiln, wharf as well as a water pump to supply ships at dock. Still, it was cursed. Lesson? The brewery, the brewery owner and the brewers are very different classes of thing. Pay attention today to how many craft “brewers” never did the actual work of brewing.

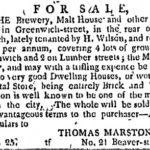

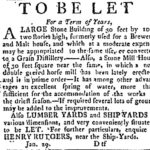

The end of the era of Lispenard’s famous brewery on the Hudson displays how the right combination of Eden’s wealth accumulation and Brooklyn’s parade of brewers can catapult descendants into decades of idle wealth. Last month, I showed how the Rutgers clan through most of the 1700s controlled a four brewery conglomerate stretching across Manhattan from what is now Tribeca south across Maiden Lane and over to Corlear’s Hook served by two farms and water from two drainage systems as well as the natural creek for which Maiden Lane is named. I lost steam at the end. In October, I wrote about the Lispenards and they married into the Rutgers dynasty when Leonard met Elsie. Their son, Anthony Lispenard, takes over the operations of the Greenwich Street brewery on the Hudson River at the foot of what becomes Canal Street. He marries well. Sarah Barclay is related to the brewing Barclays of London, England. I brought the family forward to the fire of 1804 and past it when their fortunes were made on the lands that, as we see so often, the brewing wealth allowed them to obtain but more detail can be added. In 1794, the brewery is described as brewing ale as well as table and spruce beer and Marston has joined Lispenard – Leonard Lispenard, son of Anthony. Three years later, Marston has the place up for sale even though it is occupied by a Mr. Wilson. Another two later in 1799, the brewery is up for sale again and again it is being sold by Thomas Marston. It is described as being in the rear of Trinity Church*** and “lately tenanted by H. Wilson.” It covers two lots on Greenwich and two on Lumber Streets. In March 1803, it is up for sale and described as being the brewery of Anthony, the father, despite the son Leonard being brought into the firm in 1794. John S. Moore occupies the brewery at the time of the December 1804 fire. As I showed last fall, the tide of wealth catapulted those that followed into high society throughout the 1800s.

The end of the era of Lispenard’s famous brewery on the Hudson displays how the right combination of Eden’s wealth accumulation and Brooklyn’s parade of brewers can catapult descendants into decades of idle wealth. Last month, I showed how the Rutgers clan through most of the 1700s controlled a four brewery conglomerate stretching across Manhattan from what is now Tribeca south across Maiden Lane and over to Corlear’s Hook served by two farms and water from two drainage systems as well as the natural creek for which Maiden Lane is named. I lost steam at the end. In October, I wrote about the Lispenards and they married into the Rutgers dynasty when Leonard met Elsie. Their son, Anthony Lispenard, takes over the operations of the Greenwich Street brewery on the Hudson River at the foot of what becomes Canal Street. He marries well. Sarah Barclay is related to the brewing Barclays of London, England. I brought the family forward to the fire of 1804 and past it when their fortunes were made on the lands that, as we see so often, the brewing wealth allowed them to obtain but more detail can be added. In 1794, the brewery is described as brewing ale as well as table and spruce beer and Marston has joined Lispenard – Leonard Lispenard, son of Anthony. Three years later, Marston has the place up for sale even though it is occupied by a Mr. Wilson. Another two later in 1799, the brewery is up for sale again and again it is being sold by Thomas Marston. It is described as being in the rear of Trinity Church*** and “lately tenanted by H. Wilson.” It covers two lots on Greenwich and two on Lumber Streets. In March 1803, it is up for sale and described as being the brewery of Anthony, the father, despite the son Leonard being brought into the firm in 1794. John S. Moore occupies the brewery at the time of the December 1804 fire. As I showed last fall, the tide of wealth catapulted those that followed into high society throughout the 1800s.

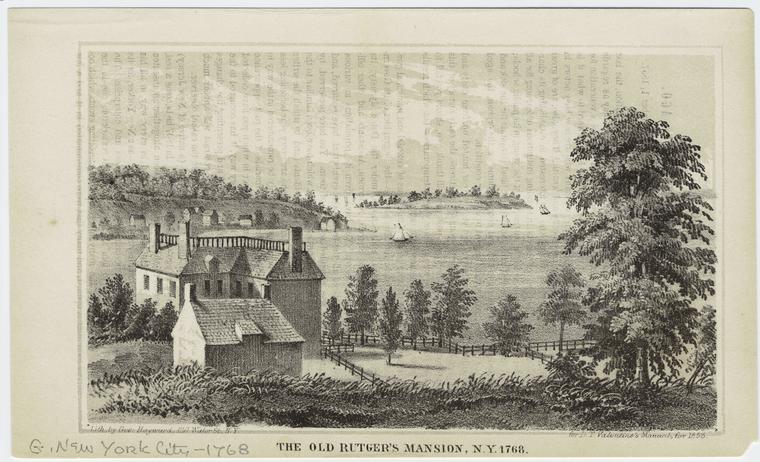

And then there was Henry Rutgers. Rutgers, you will recall, is the second or third cousin of the Lispenard controlling the Hudson River brewery as the 1800s dawn, depending on whether it is father Anthony or son Leonard we are talking about Lispenard-wise. He is a classic great American who leaves the fortune which founds Rutgers University in New Jersey. I sketched the story in February but let’s fill in a bit more. As you can see from the thumbnail, Henry was moving on from running the brewery as early as January 1793. In 1795, he is elected to the hospital board, sits on a committee considering an international treaty and has diversified commercial interests. In late 1796, he chairs a Congressional nomination meeting. By 1799, he is a leading partner in the purchase and sale of the Watkins and Flint tract. The wealth generated over generations of brewing has made him one of the richest men in the young United States. That’s his family’s house up there well before this point. It was where he lived until 1830. Likely no one has ever moved from brewing to billions and power quite like this one man. I’d be interested in thoughts of anyone comparable.

And then there was Henry Rutgers. Rutgers, you will recall, is the second or third cousin of the Lispenard controlling the Hudson River brewery as the 1800s dawn, depending on whether it is father Anthony or son Leonard we are talking about Lispenard-wise. He is a classic great American who leaves the fortune which founds Rutgers University in New Jersey. I sketched the story in February but let’s fill in a bit more. As you can see from the thumbnail, Henry was moving on from running the brewery as early as January 1793. In 1795, he is elected to the hospital board, sits on a committee considering an international treaty and has diversified commercial interests. In late 1796, he chairs a Congressional nomination meeting. By 1799, he is a leading partner in the purchase and sale of the Watkins and Flint tract. The wealth generated over generations of brewing has made him one of the richest men in the young United States. That’s his family’s house up there well before this point. It was where he lived until 1830. Likely no one has ever moved from brewing to billions and power quite like this one man. I’d be interested in thoughts of anyone comparable.

One New York brewery seems to try to buck the trend in the period 1795 to 1803. Unlike the various forms of end-of-brewing we see with Rutgers, Eden, Lispenard and even the brewery that couldn’t die in Brooklyn Ferry, the brewery that started as an 1760s plaything for George Har(r)ison, spoiled son of Francis the high placed colonial lackey of the Crown. After George dies in 1773 and the Revolution comes and goes, the brewery is in the hands of grandson, Richard. Richard reinvents himself as an ardent Republican and, like the others, leases out his brewery in the 1784 to Samuel Atlee who does not last even into 1788. The brewery itself, however, has at least one more life to live. In 1790, it is in the hands of a new partnership – Robertson, Barren and Co. It doesn’t last. Click that thumbnail. By 1792, the brewery is in the hands of Fred and Phil Rhinelander who, by 1795, who are (delightfully) selling gin alongside ale and porter. Six and a half years later, operations at the brewery change hands again as John Noble and Co. announced in the 10 December 1801 edition of the Mercantile Advertiser that they have taken the extensive brewery lately occupied by Messers Rhinelanders in Greenwich Street.” It is one of the more exciting beer notices from the era as it claims they “have been long accustomed to prepare” porter for the East and West Indies. Porter produced for export. The notice is titled “Porter Brewery.” It lasts, again, just a few years. Noble’s entire stock is sold off at an auction by his creditors in April 1805. Interestingly, the Rhinelanders’ other business kept going – including the importation of spices – until Frederick passed away. After that the lands start to be sold off at the same time city government decides to clean up this part of the Hudson shoreline. Their sugar house, however, lasts until 1968.

One New York brewery seems to try to buck the trend in the period 1795 to 1803. Unlike the various forms of end-of-brewing we see with Rutgers, Eden, Lispenard and even the brewery that couldn’t die in Brooklyn Ferry, the brewery that started as an 1760s plaything for George Har(r)ison, spoiled son of Francis the high placed colonial lackey of the Crown. After George dies in 1773 and the Revolution comes and goes, the brewery is in the hands of grandson, Richard. Richard reinvents himself as an ardent Republican and, like the others, leases out his brewery in the 1784 to Samuel Atlee who does not last even into 1788. The brewery itself, however, has at least one more life to live. In 1790, it is in the hands of a new partnership – Robertson, Barren and Co. It doesn’t last. Click that thumbnail. By 1792, the brewery is in the hands of Fred and Phil Rhinelander who, by 1795, who are (delightfully) selling gin alongside ale and porter. Six and a half years later, operations at the brewery change hands again as John Noble and Co. announced in the 10 December 1801 edition of the Mercantile Advertiser that they have taken the extensive brewery lately occupied by Messers Rhinelanders in Greenwich Street.” It is one of the more exciting beer notices from the era as it claims they “have been long accustomed to prepare” porter for the East and West Indies. Porter produced for export. The notice is titled “Porter Brewery.” It lasts, again, just a few years. Noble’s entire stock is sold off at an auction by his creditors in April 1805. Interestingly, the Rhinelanders’ other business kept going – including the importation of spices – until Frederick passed away. After that the lands start to be sold off at the same time city government decides to clean up this part of the Hudson shoreline. Their sugar house, however, lasts until 1968.

Things pass. The landmark that was Widow Rutgers’ burnt brewery of Maiden Lane is not the only end of these things. Eden, the Brooklyn Ferry brewery, cousins Rutgers and Lispenard as well as Harrison’s plaything are all gone. The backbone of the entire City’s brewing for at least the last half century pack it in by the middle of the first decade of the 1800s. It is not just that the good water is disappearing. The scions of the generation are as well. Plus, they have made their millions and the community needs their lands anyway to house the flood of new immigrants coming to make this the greatest city on the earth in the history of humankind. Arguably. In 1790, there are 33,000 people in New York City. In 1810, there are almost three times that. There is simply no place – no space – for the big dynastic brewers who dominated the southern tip of Manhattan, including some whose families had been there for most of the previous two centuries.

*Soon, the small brewers of 1795 to 1805.

**Last Saturday, fellow traveler beer historian Gerry Lorenz at the Shmaltz taproom in Clinton Park, NY made a good point after we realized we were pronouncing many of these brewers names differently. He is of the opinion that what I was pronouncing as “Med-seff” was actually “Met-calf” as in Metcalf, Ontario. Could be but I now need to explore the name as a Yorkshire artifact of the 1700s to make sure.

***That’s the first Trinity Church.

Hi Mr. McLeod. I found this post (and your blog) while researching an ancestor. According to several Longworth’s New York directories, this ancestor was a “brewer” on Broome Street in New York City for three years between 1844 and 1847. You wrote in your post: “Beer is an easy entry trade that, when done well, eventually offers wealth and perhaps even political power … brewing is a great way to shift one’s economic class upwards. A business for the ambitious to enter then later leave. ” While you were writing in present terms, would the same have been true back in the 1840s? If so, that likely would have been the reason this ancestor temporarily moved on from his trade as a ship’s carpenter (ship joiner) and then went back to it in 1847. He subsequently became very successful back in his original trade, held political office and was involved in other civic ventures. Suffice to say it appears he was ambitious. Thanks. This is a great blog!