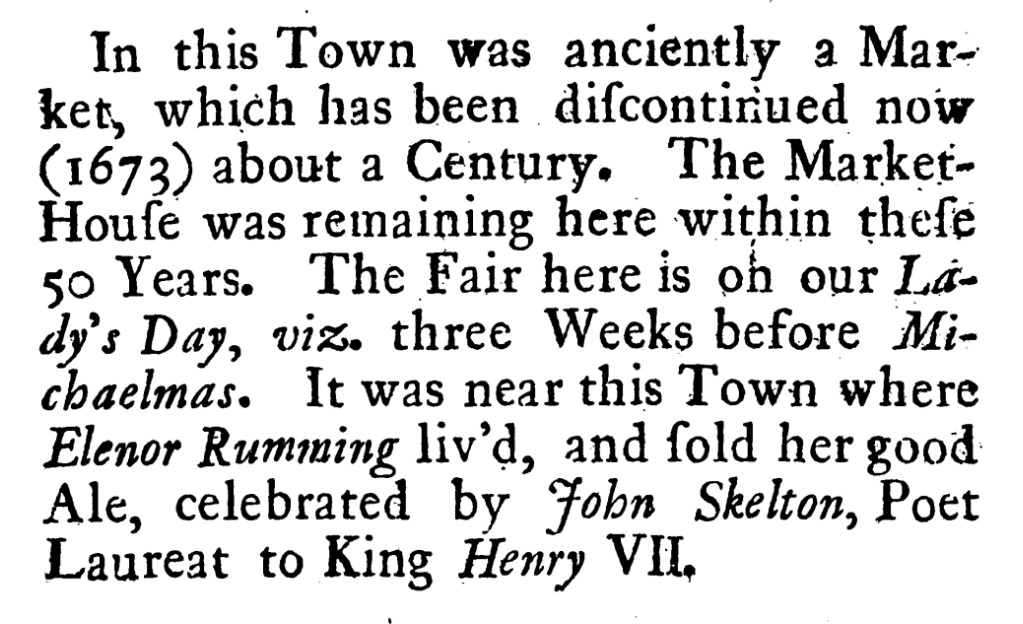

So said John Aubrey in his book Perambulation of Surrey written between 1673 and 1692. When I came across reference to the book I was hoping it was going to be an economic survey similar to The Natural History of Staffordshire from 1686 by Robert Plot. But instead it was more of a gazetteer, a recitation of things which can be found in the churches and hints as to where the bridges used to be. However, as one must, I ran a few beery words through it and the passage above sprang out. The town in question is named Letherhead alias Ledered alias Lederide by Aubrey. It is still there under the spelling Leatherhead.

And near Leatherhead lived Elenor Rumming who sold her good ale. According to Aubrey in the late 1600s. But in John Skelton’s poem, “The Tunnyng of Elynour Rummyng“ which celebrates its 500th anniversary (very probably… well, maybe) this year its really not the goodness of the ale that is celebrated.

And this comely dame,

I vnderstande, her name

Is Elynour Rummynge,

At home in her wonnynge ;

And as men say

She dwelt in Sothray,

In a certayne stede

Bysyde Lederhede.

She is a tonnysh gyb ;

The deuyll and she be syb.

The devil and she be siblings. And fat – a tonnish gyb. Yet also a “comely gyll” or Jill… “this comely dame”… hmm. Armed with only my trusty half-an-honours BA in English Lit from over 30 years ago, I thought about this as many other had before me. The poem is beyond unflattering. It’s libelous. Unless, of course, it is true. But what is the truth five centuries later? How to deal with such a thing. How true is it? In The Pub in Literature: England’s Altered State by Steven Earnshaw published in 2000 he argues:

Whilst John Skelton’s “The Tunnyng of Elynour Rumming” draws on a traditional view of the alehouse as wholly disreputable, its twist on Landland’s* alehouse scene is that Elynour’s establishment is graced only by women. Even though her name has been traved to an actual Alianora Romyng who kept the Running Horse near Leatherhead in Surrey, it is highly unlikely that the all-female drinking den is taken from actuality. According to Peter Clark, women would probably have been customers on special festive occasions, but not at other times. The level of the ballad derives from a genre which present groups of women together as gossips, and the list of names Skelton uses for the drinkers is mostly taken from a fifteen-century carol, “The Gossips Meeting.”

Highly uncomfortable stuff in these times. As Judith M. Bennett discusses in her 1991 work Misogyny, Popular Culture, and Women’s Work:

Literary critics laud the descriptive power, wittiness, and irony of The Tunning of Elynour Rummyng, yet its misogyny is blatant, vicious, and terrifying. Satirically twisting the traditional literary commendation of a woman 170 History Workshop Journal through a detailed catalogue of her appealing features, Skelton describes Elynour Rummyng in careful detail as a grotesquely ugly woman. Beginning by telling us that she is ‘Droopy and drowsy/Scurvy and lousy’, Skelton then details her features: her face bristles with hair; her lips drool ‘like a ropy rain’; her crooked and hooked nose constantly drips; her skin is loose, her back bent, her eyes bleary, her hair grey, her joints swollen, her skin greasy. She is, of course, old and fat. She is also ridiculous, wearing elaborate and bright clothes on holy days and cavorting lasciviously with her husband like – as she proudly tells it in Skelton’s poem – ‘two pigs in a sty’…

In the 2008 text The Culture of Obesity in Early and Late Modernity: Body Image in Shakespeare, Jonson, Middleton, and Skelton by E. Levy-Navarro there is another somewhat related view in the chapter “Emergence of Fatness Defiant: Skelton at Court.” See, Skelton wasn’t just anyone. In the late 1400s, he was he was appointed tutor to Prince Henry, later King Henry VIII of England. Bennett states “Skelton’s social world was broad, running from the royal court and various noble households, through the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge, to the lanes and fields of his parish at Diss, in Norfolk.” Levy-Navarro builds on the idea to take another view – that in the last decade or so of his life, Skelton was on the outs with court and in fact may have had a strong distaste for court:

Much scholarship has assumed that Skelton aligns himself with men in power. A long line of modern scholars makes this point when they assume that Skelton is a modern “man”… who aligns himself with the men of Henry’s court against the lowly women of the tavern world.

Levy-Navarro states that such readings ignore the discontent and defiance in Skelton’s work and, further, that “The Tunnyng of Elynour Rummyng” is a defiant statement against the courtly styles and superficiality:

Skelton offers outrageous, bulging and revolting bodies of the tavern women. These bodies may not yet be “fat” per se, but they are protofat to the extent to which they are seen as revolting against a civilized ethic.

As such, Skelton is observing a the point of the English Renaissance at which manners come into being in a sense that we can recognize as early modern, materialistic self-made people showing wealth and power through a display of expensive and even architectural clothing as well as through the dismissal of intellectual and priestly men like Skelton. In this way of reading the poem, Skelton may not admire or completely side with Elynour Rummyng but he expresses something admirable about her liberty and perhaps is noting the impending passing of that sort – as well as his own sort – of life.

Taking all that in hand, the poem is no longer just a now grotesque, obviously misogynistic romp through the low life of those found in her tavern but also a larger social commentary. It might well be, yes, making fun of the horrors found there but also lamenting a day when such a free and lewd life could no longer possible given the plans for society being made by the newly formed betters to be found in court.

If that is the case, as with science-fiction today, the structure of the alternate reality needs firm grounding in truth as it was understood by the audience. Farce and fantasy do not mix well. There needs to be substance that is credible for the commentary to be acceptable to its contemporary audience. Let’s have a look from, for ease, a modern reading of part of the text which can be found here. Notice first that the tavern sits on a hill, near a road and is readily accessible:

Now in cometh another rabble:

And there began a fabble,

A clattering and babble

They hold the highway,

They care not what men say,

Some, loth to be espied,

Start in at the back-side

Over the hedge and pale,

And all for the good ale.

(With Hey! and with Ho!

Sit we down a-row,

And drink till we blow.)

Sounds like good fun for these ale-slugging women patrons. Note also that the ale is made in the tavern.. the ale house – with a bit of a special twist as this section in the original indicates:

But let vs turne playne,

There we lefte agayne.

For, as yll a patch as that,

The hennes ron in the mashfat ;

For they go to roust

Streyght ouer the ale ioust,

And donge, whan it commes,

In the ale tunnes.

Than Elynour taketh

The mashe bolle, and shaketh

The hennes donge away,

And skommeth it into a tray

Whereas the yeest is,

With her maungy fystis :

And somtyme she blennes

The donge of her hennes

And the ale together ;

And sayeth, Gossyp, come hyther,

This ale shal be thycker,

And flowre the more quicker ;

For I may tell you,

I lerned it of a Jewe,

Whan I began to brewe,

And I haue founde it trew ;

Drinke now whyle it is new ;

So chickens run around the tavern and even into the mash vat, leaving their droppings of dung on the fermenting ale. As learned from a Jewish brewer when she was young, the hen-dung is skimmed but sometimes some is left in the yeast tray so that the ale might be thicker and the yeast “flower” quicker. And it is not just chickens. She has to “stryke the hogges with a clubbe” because they have drunk up her “swyllynge tubbe”! Note how many of the elements of her brewery operations are described.

Look a bit more at more of the language about the ale. It is offered both new and stale. It is nappy and noppy. It is stated to be “good” twice. It is also worthy of a lot in payment or barter so some pledge their hatchet and their wedge, some their “rybskyn and spyndell”, even their “nedell and thymbell” because it is that good:

Some haue no mony

That thyder commy,

For theyr ale to pay,

That is a shreud aray ;

Elynour swered, Nay,

Ye shall not beare away

My ale for nought,

By hym that me bought…

By him that me bought. Christ. It is all so excellent even if, effectively, otherworldly. You may read it many ways but what you are reading is a window not only to a now uncomfortable commentary on early modern life but life within a tavern. Even if a ribald farce, it’s still a tavern as they would have known it. Lovely.

Blimey, I used to work near Leatherhead. And the pub’s still there too: http://www.running-horse.co.uk/

Not sure when I’ll next be down that way though.

Interesting. It is clear in the poem that the ale house is on a hill but in reality it is by the river. Maybe that is a big red flag that it is an inversion joke. My little thought that it might be a parody of court by making everything high lowly, everything male female. Like how Shakespeare later talked about Elizabethan politics by setting stories in Rome.

The pub is at the bottom of Bridge Street, Leatherhard, beside the river Mole. Bridge street is a moderately steep hill, rising probably 150ft or so up to the High Street. So – Yes it is on a hill, and it is beside the river.