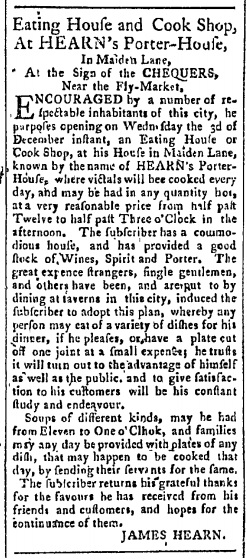

On 2 December 1783, James Hearn had a noticed placed in the New York Morning Post for his new business, opening the next day in Maiden Lane. Hearn’s Porter-House would offer wines, spirits and porter as well as a variety of dishes hot and in any quantity the single gentleman might desire. He even offered take away meals to anyone “sending their servants for the same.” A particular point is made about his soup. And then you notice the hours of operation. The soup is available from 11 am to 1 pm. The meals will be served from 12:30 noon to 3:30 pm. There’s a certain level of constraint at play.

On 2 December 1783, James Hearn had a noticed placed in the New York Morning Post for his new business, opening the next day in Maiden Lane. Hearn’s Porter-House would offer wines, spirits and porter as well as a variety of dishes hot and in any quantity the single gentleman might desire. He even offered take away meals to anyone “sending their servants for the same.” A particular point is made about his soup. And then you notice the hours of operation. The soup is available from 11 am to 1 pm. The meals will be served from 12:30 noon to 3:30 pm. There’s a certain level of constraint at play.

One of the great things about researching through newspaper archives is how everything is contextualized for you. It is easy to think, read and write about beer in a bubble if all you look at is information about beer. The notice for Mr. Hearn’s new business is placed in the newspaper one week after New York’s Evacuation Day, the day when the last of the British troops left the City after months of evacuations of the Loyalists who became one of the foundations of the nation to the north, Canada. Just two weeks before the proposed opening of the Porter-House, the Governor of New York placed a Proclamation in the Royal Gazette on 19 November 1783, the last edition, confirming how the withdrawal of British troops would occur. Notice that the Governor placing the ad was George Clinton and not Royal commander Sir Guy Carleton. The notice was published on page three.

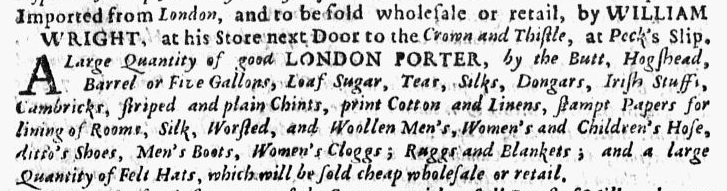

So, why was it a porter-house? Porter was certainly prized in the years after the end of the American Revolution. As we saw a few weeks ago, in 1798 Caleb Haviland’s porter vault in what is now Lower Manhattan stocked both London porter and American porter. It was “in the best possible order” – ripe and brisk. But the relationship with the drink started at least half a century before that. In the New York Gazette of 5 February 1750, an extract of a letter was published from a new colony at Nova Scotia, written the previous August, praising the provisions… except the lack of “a Pot of good London Porter and Purl.” The earliest advertisement that I have seen for porter in New York City was published in the same paper on 23 December 1751 in a mixed cargo from Scotland* containing cloths and linens, steel and writing paper… plus usquabaug – aka whisky. It appears late in quite a long list of goods. One year later on 18 December 1752, an ad is placed again in the Gazette which places the porter right to the forefront in a range of sizes from butts to five gallon barrels:

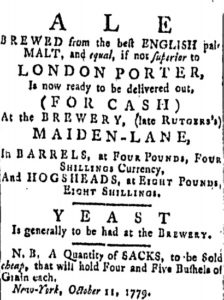

Jumping ahead, we find this ad from 1779 – the middle part of the war – which sets out some very interesting things. If you read it carefully, you will see it is not an ad for porter but an ad for a beer that is claimed to be as good as London’s porter. Imported porter is the standard to be met in the marketplace. The brewery is the one in Maiden Lane which has been taken over from the Revolutionary Rutgers clan of brewers. It’s brewed with English grain, which would be reasonable given how the city was surrounded by fields better known as “no man’s land.” War is bad for beer. But maybe not so bad for beer importation. Even in the middle of 1781, porter was being imported and made available along with other pleasures such as double spruce ale and coffee. By the summer of 1783, well after the impending surrender is inevitable, things are not as pretty. The Royal American Gazette of 7 August 1783 shows that everything is for sale: the billiards table in a house being advertised for leave, plenty of mess beef and pork in barrels, passage for your family to Canada and – yes – still those bottles of porter. All offered in return for cash or, as one notice states, “light and foreign gold taken in payment.” A few weeks later, the British are gone and Mr. Hearn has opened his Porter-House.

Jumping ahead, we find this ad from 1779 – the middle part of the war – which sets out some very interesting things. If you read it carefully, you will see it is not an ad for porter but an ad for a beer that is claimed to be as good as London’s porter. Imported porter is the standard to be met in the marketplace. The brewery is the one in Maiden Lane which has been taken over from the Revolutionary Rutgers clan of brewers. It’s brewed with English grain, which would be reasonable given how the city was surrounded by fields better known as “no man’s land.” War is bad for beer. But maybe not so bad for beer importation. Even in the middle of 1781, porter was being imported and made available along with other pleasures such as double spruce ale and coffee. By the summer of 1783, well after the impending surrender is inevitable, things are not as pretty. The Royal American Gazette of 7 August 1783 shows that everything is for sale: the billiards table in a house being advertised for leave, plenty of mess beef and pork in barrels, passage for your family to Canada and – yes – still those bottles of porter. All offered in return for cash or, as one notice states, “light and foreign gold taken in payment.” A few weeks later, the British are gone and Mr. Hearn has opened his Porter-House.

Why a porter-house? It was a last luxury of the previous regime. It is stored in cellars and is best when left to age down there. It needs to ripen if it’s going to be brisk. So, in the weeks and months after the peace breaks out and folk like the hatters Bickers* and Son are returning from the war triumphant, the goods in storage needed to be put to use. The porter still needed to be drunk. Mr. MacPherson had the same idea and opened his porter house a few weeks before the British left. Folk were making do as the new nation had just begun to make its way.

*I did not know until today that a “snow” was a sailing ship somewhat similar but distinct from a “brig.”

** presumably.

*** a rather capable man for a hatter, Colonel Bickers.