Thoughts. Hmm. That is code for “Alan has not researched this enough” but let’s see what we can find out on a pleasant Saturday afternoon. This post is a follow up to one I posted on 10 June which asked the question of when the first hops were exported from the United States. In this post, I am looking a bit more at where the hops were coming from, especially before the middle third of the 1800s by which time central New York had become the main source of hops. Up there is a snippet from an 1802 article in The Bee, a newspaper from Hudson New York in 1802 which may indicate why the domestic and international trade were not necessarily without connection. More about that later.

A good first step is at the beginning and that could be the diary of Thomas Minor, a gent living in Stonington at the eastern end of Connecticut who recorded the cycle of his farming life from 1653 to 1684. Stonington actually predates the establishment of Connecticut in 1662 so Minor must have been one of the first European settlers there. He was born in Somerset, England in 1608 and came to the the Massachusetts colony in 1630, moving about before settling in Stonington to farm and also serve as a local government official.

His diary is spare, recording a month in a brief paragraph like this passage from September 1661:

…the 8th we had made an end of hay making monday I gathered hops & the 14 day I Commed flax my sons was all about the Cart & wheels sabath day the 15th good-man Cheesbrough spake to me about moving mr Brigden from fathers deaken parke washeare & sabath day the .22. monday 23. we Caught the wild horse the 20th of this month mr picket & we parted the sheep…

As you would expect, Minor kept a diversified subsistence farm with cattle and horses as well as oats, wheat, turnips, peas, apples, chestnuts and Indian corn all being mentioned. He was not picking wild hops in the woods. He weeded the hops in the third week of June 1663 and again on 22 April 1670. On 17 April 1673, he “diged up the hops” which indicates that he is propagating them in some manner. He also records gathering hops on 8 September 1661, 7 September 1668, 31 August 1669, 15 September 1670, 1 September 1671 and 2 September 1680 when he is 72 years old.

He also makes barrels of cider during many years, pressing from late in the summer and on into autumn. He doesn’t mention barley or beer making. He trades for goods with others. On 19 January 1679 he delivered 30 barrels of oats to be paid in “a barle of good malases and other barbades goods” so it is entirely reasonable that he traded away his hops and traded for ale.¹ Interesting to note that he is trading at that early date for good from the sibling English colony of Barbados. I noticed that the word “bread” is only recorded once so the brewing of ale might have been such a commonplace that it was no worth mentioning.

Inter-colonial trade was an important thing. In a rather condensed paragraph in “A Bitter Past: Hop Farming in Nineteenth-Century Vermont” by Adam Krakowski, the extent of the New England hops trade in the first half of the 1700s is described:

While seventeenth- and early-eighteenth-century accounts of hops in the colonies are rare, a law passed in the English Parliament in 1732 under the reign of King George II, titled “An Act for importing from His Majesty’s Plantations in America, directly into Ireland, Goods not enumerated in any Act of Parliament, so far as the said Act relates to the Importation of Foreign Hops into Ireland,” suggests just how widespread and successful the hops crops were in America at that time. Outlawing the importation of hops from America through Ireland and into England implied that the hops were abundant enough to fulfill domestic demand as well as supplying an export trade. The Massachusetts Bay Colony had already established itself as an important hops supplier, shipping hops to New York and Newfoundland as early as 1718.

If that suggestion, entirely reasonable, about the 1732 British statute is correct, such a date for the first export from the colonies to Ireland would push back the use of American hops in UK brewing about 80 years from the earliest date Martyn has identified. It may actually go further back than that. In an 1847 letter from Earl Fitzwilliam to Rev. Sargeaunt discussing aspects of the Irish Question, the following is stated:

…the hop growers were to have their share in the monopoly, and, by the 9th Anne, c. 12, the import of foreign hops into Ireland was to be adjudged a common nuisance. Early in the reign of George 2nd, some doubts arose, whether, by an act then recently passed, the prohibition upon the import of foreign hops had not been incidentally—unintentionally—repealed. A return of the common nuisance was dreaded, the hop growers were on the alert, and the legislature of the ruling power immediately passed the 5th Geo. 2, c. 9, in which it is declared that the 9th Anne, c. 12, shall remain and continue in full force—consequently, that the import of foreign hops into Ireland was as great a nuisance in 1732 as in 1710.

The statute known as 9 Anne, c.12 from 1710 appears to have been a fairly comprehensive statute related to the imperial brewing industry. Section 24 prohibited the use of hop alternatives like broom and wormwood and also was the first imposition of a duty on hops. All of which makes sense as the primary subject of 9 Anne, c. 12 was taxation. If you are going to tax something you need to exclude similar things not being taxed. So no importation of hops and no use of hop replacements.*

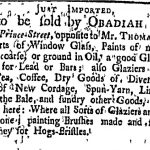

Back to the newspapers. In the decades immediately before, and even during the Revolution, hops were coming into from siblings amongst the soon to be united colonies. To the right is an excellent notice which Craig has discussed from New York’s Morning Post of 6 March 1749 in which Obadiah Wells offered a wide range of good, most “too tedious to mention,” including bales of “Boston Hops.” in 1766, according to the 19 May edition of the New York Mercury, a ship on the Boston-NY route gave notice that it was sailing in ten days but that it still had hops for anyone who came down to the wharf.**

Back to the newspapers. In the decades immediately before, and even during the Revolution, hops were coming into from siblings amongst the soon to be united colonies. To the right is an excellent notice which Craig has discussed from New York’s Morning Post of 6 March 1749 in which Obadiah Wells offered a wide range of good, most “too tedious to mention,” including bales of “Boston Hops.” in 1766, according to the 19 May edition of the New York Mercury, a ship on the Boston-NY route gave notice that it was sailing in ten days but that it still had hops for anyone who came down to the wharf.**

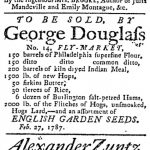

Perhaps counter-intuitively, hops from across the ocean were also traded in New York City not long after the end of the war. To the right is an notice from the New York Morning Post of 17 March 1787, less than four years after Evacuation Day when the city which had remained loyal was turned over to the new United States. Notice how the garden seeds being English are highlighted. Notice also the 1500 lbs of “new hops” for sale. Are they also English? It is not claimed. Compare the volume as well as description to this notice from New York’s Independent Journal on 10 March 1784 in which a few bales of best English hops are on offer. The old country still has some draw.

Perhaps counter-intuitively, hops from across the ocean were also traded in New York City not long after the end of the war. To the right is an notice from the New York Morning Post of 17 March 1787, less than four years after Evacuation Day when the city which had remained loyal was turned over to the new United States. Notice how the garden seeds being English are highlighted. Notice also the 1500 lbs of “new hops” for sale. Are they also English? It is not claimed. Compare the volume as well as description to this notice from New York’s Independent Journal on 10 March 1784 in which a few bales of best English hops are on offer. The old country still has some draw.

Soon, however, things shift. On 22 March 1790, the Albany Gazette advocated for the production of beer, cider and hops as there were no duties to be paid upon them compared to the trade in spirits, rum and wines. Decisions related to the development of agriculture were being framed by geopolitical tensions and resulting tariffs.

Soon, however, things shift. On 22 March 1790, the Albany Gazette advocated for the production of beer, cider and hops as there were no duties to be paid upon them compared to the trade in spirits, rum and wines. Decisions related to the development of agriculture were being framed by geopolitical tensions and resulting tariffs.

In 1802, as noted above and seen to the right, The Bee from Hudson, New York published an article on increasing American domestic manufacturing as opposed to relying on foreign trade for necessities. It seems to echo British concerns from one hundred years before. This essay is attributed to Ben Franklin – even though he had been dead for about twelve years. Whoever wrote it, the essayist reflected the new Jeffersonian era in the new century which took American self-sufficiency and exceptionalism to a new level. And hops were part of that, highlighted as a key commodity well suited to increased production for domestic consumption. Makes sense. European tariffs impeded the hops trade otherwise.

In 1802, as noted above and seen to the right, The Bee from Hudson, New York published an article on increasing American domestic manufacturing as opposed to relying on foreign trade for necessities. It seems to echo British concerns from one hundred years before. This essay is attributed to Ben Franklin – even though he had been dead for about twelve years. Whoever wrote it, the essayist reflected the new Jeffersonian era in the new century which took American self-sufficiency and exceptionalism to a new level. And hops were part of that, highlighted as a key commodity well suited to increased production for domestic consumption. Makes sense. European tariffs impeded the hops trade otherwise.

Tariffs were imposed on imports in to the United States in return and for reasons which were argued positive political policy. On 26 January 1810, an article in the Albany Register, right, argued for raising the duty on foreign distilled spirits beyond 50% “…to encourage our own breweries, distilleries, molasses importers and growers of hops, grain, fruit and sugar cane…” In the context of an expanding national economy as well as jingoism, the domestic hop industry was worth protecting and expanding. So slap on a tariff.

Tariffs were imposed on imports in to the United States in return and for reasons which were argued positive political policy. On 26 January 1810, an article in the Albany Register, right, argued for raising the duty on foreign distilled spirits beyond 50% “…to encourage our own breweries, distilleries, molasses importers and growers of hops, grain, fruit and sugar cane…” In the context of an expanding national economy as well as jingoism, the domestic hop industry was worth protecting and expanding. So slap on a tariff.

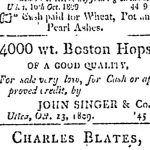

This home grown hop strategy might well have been key to the development of the market. The Republican Watch Tower, also of New York, ran an ad on 9 December 1801 offering 35 sacks of “fresh hops” for sale. Hard to be fresh by that date if shipped across the ocean – but not impossible. To the right is an ad from Utica NY’s Columbian Gazette from 18 November 1809 showing 4,000 lbs of domestic “Boston hops” for sale. In Horatio Spafford’s Gazetteer of 1813, it states that Utica had a population of 1700 and Oneida County as a whole had four breweries. According to the hopping rates in the NY State Senate report of 1835, that one supply of hops is enough for well over 1,000 barrels of ale. “Boston hops” were on still offer in the New York City market in 1818 according to this ad in the Gazette from 9 November and this one from the Evening Post from 20 November. The Commercial Advertiser of New York praised the 1823 Massachusetts hop crop in an October 6th article. The same newspaper on 30 December 1826 carried a notice for the sale of Vermont hops which had been brought down into the city, twelve hundred pounds worth.

This home grown hop strategy might well have been key to the development of the market. The Republican Watch Tower, also of New York, ran an ad on 9 December 1801 offering 35 sacks of “fresh hops” for sale. Hard to be fresh by that date if shipped across the ocean – but not impossible. To the right is an ad from Utica NY’s Columbian Gazette from 18 November 1809 showing 4,000 lbs of domestic “Boston hops” for sale. In Horatio Spafford’s Gazetteer of 1813, it states that Utica had a population of 1700 and Oneida County as a whole had four breweries. According to the hopping rates in the NY State Senate report of 1835, that one supply of hops is enough for well over 1,000 barrels of ale. “Boston hops” were on still offer in the New York City market in 1818 according to this ad in the Gazette from 9 November and this one from the Evening Post from 20 November. The Commercial Advertiser of New York praised the 1823 Massachusetts hop crop in an October 6th article. The same newspaper on 30 December 1826 carried a notice for the sale of Vermont hops which had been brought down into the city, twelve hundred pounds worth.

What have we learned? American farmers have produced hops from the earliest days of settlement. As we saw with early Quebec, this aspect of self-sufficiency is as one might expect from the colonial expansion of a beer drinking culture. The trade in those hops as been subject to tariffs and other forms of regulation where local markets perceive that they are in need of protection from the trade in foreign goods competing with local products.*** But in a rapidly expanding marketplace such tariffs may serve to foster a stable complete internal economy. As a result, as Americans turned away from dependency on its eastern coast during the first decades of the 1800s to the opportunities inland, hops would go with them.

* I have not laid my hand on a full copy of the original statute, just this later version 9 Anne c.12 with revoked sections. This summary from 1804 indicates to me that it was a comprehensive regulation of the hops market.

** The Krakowski article notes another similar “Shipping records for the schooner Bernard out of Boston destined for New York include 3,000 pounds of hops in February 1763.”

*** Sound familiar?

¹ Update: the buying and selling of ale and brewing ingredients in a small 1808 New York community is recorded in this 2014 post on the first Vassar book.