I need a new project. The writing and working and new kitten stuff is simply not enough. So when I was reading Ron Pattinson‘s new book The Home Brewers Guide To Vintage Beer yesterday as the six year old did not do much during a kids’ basketball practice at the Y, I was struck by this passage on page 11:

I need a new project. The writing and working and new kitten stuff is simply not enough. So when I was reading Ron Pattinson‘s new book The Home Brewers Guide To Vintage Beer yesterday as the six year old did not do much during a kids’ basketball practice at the Y, I was struck by this passage on page 11:

The earliest porters and stouts were brewed from 100 percent brown malt… It was custom to use straw as a fuel in the final stage of the kilning, where the temperature was increased dramatically.

See, in these hop-crazed times we worship a false idol, a flavouring agent. That error has spawned a thousand flavoured beers posing as craft. But we know that adding watermelon or lye or New Zealand hops to a beer only succeeds in making the beer taste of the adulteration. It is time that the focus of brewing returned to the making of better beer. And that means paying attention to the malt.

Which is the point of the LDBK. See, when I was a bad home brewer I liked to manipulate the malt, I would toast it immediately before mashing to make the oils more volatile and available. I used to let some malts soak for days in cold water in the fridge and pour the resulting tea into the boil right at the end. It worked. It was easy. But ever since I tried the 1855 collaboration porter brewed by Pretty Things and Ron, I have wanted to taste what should be considered the holy grail of brewing: pre-1800s beer made with proper diastatic brown malts.

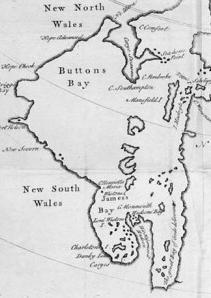

That is where the LDBK comes in. See, what needs to be determined is how diastatic brown malt is made. What we know is that it was made of malt and that it was made by kilning. What has been forgotten is how the malt got darkened without destroying the enzymic properties of pale malt that allows the grains’ natural starches to convert to fermentable sugars. This conversion is something that can and should happen in every home every second week. Through collective experimentation and statistical analysis of results, it may be possible to establish the practical point at which pale malt may be toasted and darkened to create brown malt as well as the manner in which it might be done to protect the enzymic action. That in fact is the motto of the LDBK. Protect the Enzymic Action. What is the Latin for that?

So, start kilning and mashing. It takes a kilo of pale malt, pots and pans, graph paper and curiosity. While it may be that the critical feature is pre-kiln, that mention of the use of straw and flash heating may be key. The trick might be to darken the outside so fast that the inside is not fully heated. Then mash it in small batches to see if the resulting 66C porridge goes sweet. Like a rare steak on the grill, the point might be to preserve both characteristics through the process. Just a theory. But that’s where all great advances in human understanding begin. With a theory. And some graph paper. You in?

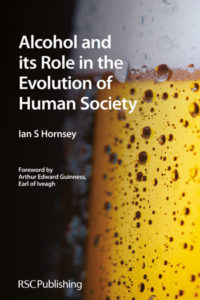

That is Alcohol and its Role in the Evolution of Human Society by Ian S. Hornsey. I had no idea. In a work of beer writing that is still trying to find its way, seeking to evolve from fanboy gushing or trade focused boosterism or underdeveloped efforts at business journalism, Hornsey’s 2004 book

That is Alcohol and its Role in the Evolution of Human Society by Ian S. Hornsey. I had no idea. In a work of beer writing that is still trying to find its way, seeking to evolve from fanboy gushing or trade focused boosterism or underdeveloped efforts at business journalism, Hornsey’s 2004 book  This is another book from Brewers Publications that bridges the worlds of brewers and drinkers. As with Stan’s excellent

This is another book from Brewers Publications that bridges the worlds of brewers and drinkers. As with Stan’s excellent