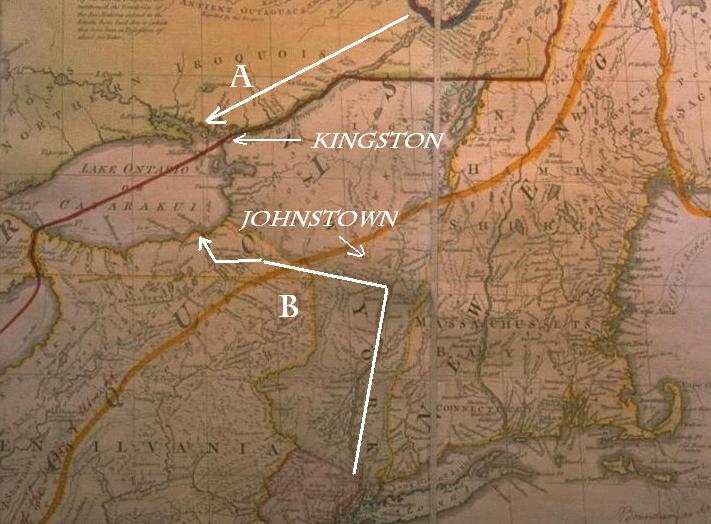

I have found myself wondering what the heck I am doing with all this Albany Ale stuff but I’m not too concerned. It is interesting in itself and I think it is informing me on a pretty interesting big picture question – what makes the Albany and the Hudson River so different from the St. Lawrence Valley, my river. You will recall that during Ontario Craft Beer week this past June, I wrote a number of posts on the development of Ontario after the American Revolution but it is important to remember that, like the Dutch in the Hudson, the upper St. Lawrence also had a 1600s existence when it was all New France.

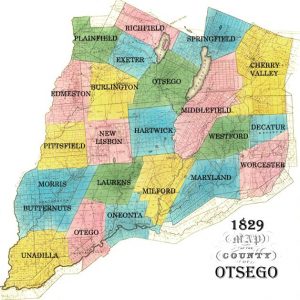

The big question I have is why did Albany create this export trade while my city did not? There are some basic answers around the odd semi-autonomous existence of early Albany while Kingston has been firmly tied to its Empires. Also, there is simple geography with Albany being a deep water seaport while Kingston has always sat behind rapids and locks. Difference makes sense. But is that it? Looking more closely, there are the details. And details can get obsessive with a range of ways to get at them:

- Who is doing what? You can find this information in newspaper ads, business directories and gazetteers. People have always been obsessed with what others are doing and putting it in a central place so thoers can see it. Google is making this information available to all for free without travel.

- How is it being taxed? Beer has attracted excise and sales taxes for centuries. This is Professor Unger’s approach. I have not really gotten into this level – yet.

- What is being brewed? Ron Pattinson’s obsession with day to day brewing logs is a less to us all in detail. And he is getting some of the brewing replicated as his trip to Boston this weekend shows.

- Who is allowed to deal with beer? Beer is also regulated along with all booze. Tavern and brewery license records exist as do the court records of applications and charges for violations. Taverns and Drinking in Early America by Salinger is largely built on this sort of analysis.

- Where does the beer go? Pete Brown has taught us a lot about that. Mapping trade routes is another avenue to this stuff. I have asked about Dutch East India ale as well as Bristol’s Taunton ale. What made for the demand for these beers and what made them eoungh good value to the other end of the world to buy them?

- Beyond all this, there is Martyn. The funny thing about Martyn’s work for me is that I can’t understand where he gets his data – his focus on words amazes me. I don’t know if I could be so elemental and authoritative. But West Country White Ale inspires.

So, there is a lot there – a lot for anyone in any town to use to figure out the path of their local brewing trade. And there are a lot of other people hunting as well. Me, I have no idea what I will learn about Albany or Kingston or beer or anything else. But it is worth the hunt. And why not? Weren’t we all supposed to be citizen journalists, historians and novelists? Isn’t that the promise of the internet or is it really more like that personal jet pack we were all supposed to have by now? I think you might all want to get all be scratching around a bit – even if not as obsessively as others.

Anyone interested in beer in Canada – or even colonial North America – really ought to have this book on the shelf. 2009’s

Anyone interested in beer in Canada – or even colonial North America – really ought to have this book on the shelf. 2009’s  Remember

Remember

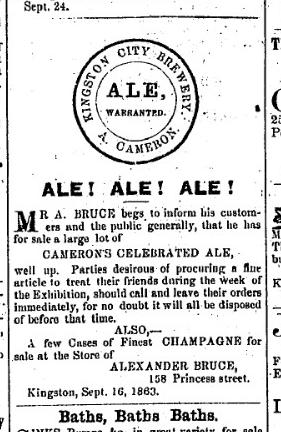

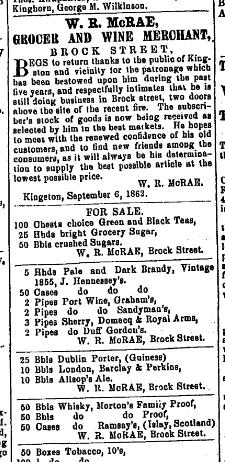

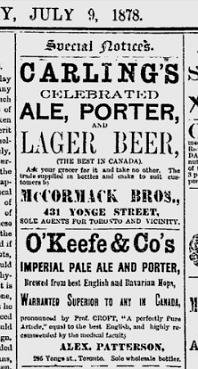

Kingstonians were not only enjoying local brewed beers, however celebrated, in the early 1860s as the ad to the left from the same paper’s

Kingstonians were not only enjoying local brewed beers, however celebrated, in the early 1860s as the ad to the left from the same paper’s

They had to make products that both reflected and appealed to their clients and the environment. The had to go with a shot of whisky – whether it was made with barley or rye.

They had to make products that both reflected and appealed to their clients and the environment. The had to go with a shot of whisky – whether it was made with barley or rye.

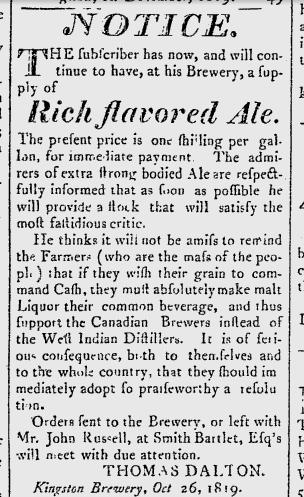

So, how to get beer to Kingston when one route is under constant risk of attack and the other is in enemy hands? Well, you don’t. You have to wait to grow crops and then you have to feed yourself, sell some off for cash and then sooner or later you get to the point that there is enough extra to make beer. Have a look at that ad we looked at

So, how to get beer to Kingston when one route is under constant risk of attack and the other is in enemy hands? Well, you don’t. You have to wait to grow crops and then you have to feed yourself, sell some off for cash and then sooner or later you get to the point that there is enough extra to make beer. Have a look at that ad we looked at