Big news out of Lyme Regis in Dorset, England as they are reviving or at least reinterpreting a festival that ended back in 1610.

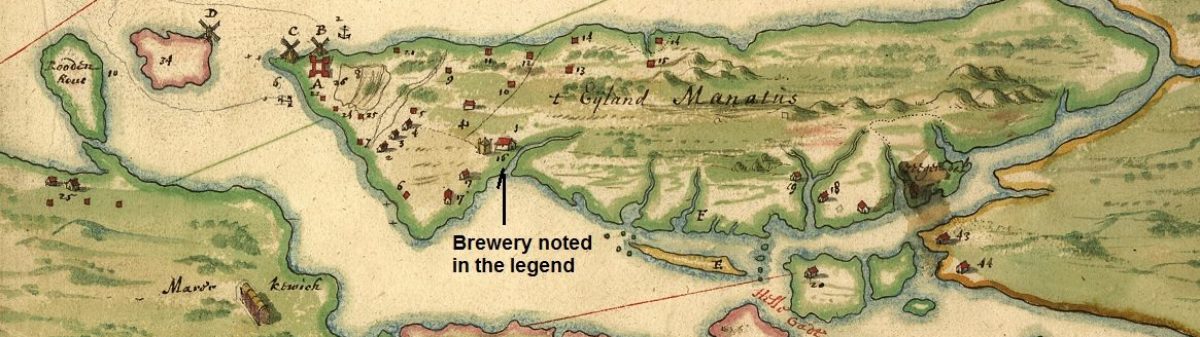

The ale will be in full flow at Lyme Regis when the town hosts its first beer festival in 400 years. A festival called The Cobb Ale started in Lyme in the 14th century and lasted for around 250 years. The annual knees-up was held to raise money for the maintenance of the Cobb but it was stopped around 1610 by the Puritans. Now three local brewers, the Mighty Hop Brewery and Town Mill Brewery, both in Lyme Regis, and North Chideock’s Art Brew, will revive the tradition for a one-day festival in March.

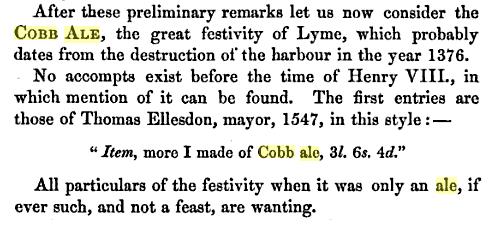

Friggin’ Puritans. They ruin all the fun. But there is fun – real fun – to be had and it is not some phony baloney made up thing. You know that’s true because the Victorians wrote about it. That clip way up above is from the 1856 books called The Social History of The People of the Southern Counties by George Roberts who spends twenty pages or so – from 327 to 346 or so – on the history of the Cobb Ale festival. It is great stuff.

OK, it may be an utter lie as might be the renewal but it is very entertaining. Martyn and other cleverer folk than me know more about this stuff but the very idea that something celebrating 1376 could be celebrated still is very appealing to me. I might take it so far that, for me, the distinction between “ale” as festival and “ale” as the juice that makes the community festive described by both Martyn and George above escapes me a bit in the light of the knowledge that they who celebrated knew the resonance of one meaning to the other. It’s a bit like “party” as both noun and verb in the sense that one parties at the party. Having an ale at an ale must have been all quite affirming.

I get cranky. Especially when I have had a cold since Thursday and couldn’t get out on the snowshoes this weekend as planned. Heck, I really could not maintain much of a level of consciousness given the fever here, the aches there and the surreal effect of cold medication. Not prime time for the beer fan. So, it’s a good thing we have books for these drier stretches. I got this one in the mail a few months ago. Been wondering when I would post about it. I really should post more reviews of CAMRA’s excellent books but when this rare review copy came, I noticed my street address was off by about 127 front doors. Some guy two tenths of a mile away must have a great collection.

I get cranky. Especially when I have had a cold since Thursday and couldn’t get out on the snowshoes this weekend as planned. Heck, I really could not maintain much of a level of consciousness given the fever here, the aches there and the surreal effect of cold medication. Not prime time for the beer fan. So, it’s a good thing we have books for these drier stretches. I got this one in the mail a few months ago. Been wondering when I would post about it. I really should post more reviews of CAMRA’s excellent books but when this rare review copy came, I noticed my street address was off by about 127 front doors. Some guy two tenths of a mile away must have a great collection. Does that make sense? My co-workers have family in Wisconsin which means I get a share in

Does that make sense? My co-workers have family in Wisconsin which means I get a share in

My math is pretty bad but not as bad as the news out of Liverpool in central New York near Syracuse that the Galeville Grocery has shut after being a grocery store since 1926 and a building since 1854. Reader Jack forwarded me

My math is pretty bad but not as bad as the news out of Liverpool in central New York near Syracuse that the Galeville Grocery has shut after being a grocery store since 1926 and a building since 1854. Reader Jack forwarded me