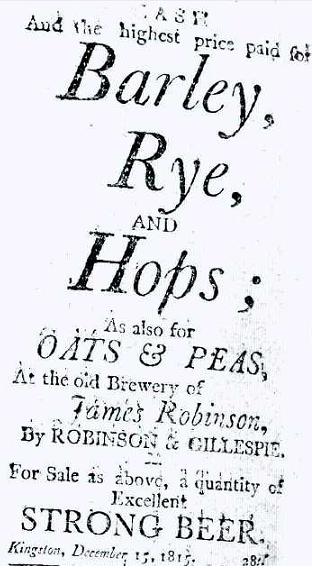

The ad is from page 4 of the Kingston Gazette, 6 January 1816. You can see at the bottom that it was placed on 15 December 1815. So many questions. What were Messrs Robinson and Gillespie up to? Why is rye placed between barley and hops in the large font while oats sit down there with the peas? Also, is “strong beer” something separate, something identifiable to the Kingstonian a year after the war with America? You will recall that a few months later in April, Albany strong beer is for sale. It also comes just a month after Richard Smith’s notice for plain “beer” – so was “strong beer” something they had the taste for still, almost 40 years after having to flee from their central NY homes at the beginning of the American Revolution? And why is it not “ale” when described in the Kingston papers?

The ad is from page 4 of the Kingston Gazette, 6 January 1816. You can see at the bottom that it was placed on 15 December 1815. So many questions. What were Messrs Robinson and Gillespie up to? Why is rye placed between barley and hops in the large font while oats sit down there with the peas? Also, is “strong beer” something separate, something identifiable to the Kingstonian a year after the war with America? You will recall that a few months later in April, Albany strong beer is for sale. It also comes just a month after Richard Smith’s notice for plain “beer” – so was “strong beer” something they had the taste for still, almost 40 years after having to flee from their central NY homes at the beginning of the American Revolution? And why is it not “ale” when described in the Kingston papers?

I just finished The Lion, the Eagle and Upper Canada by Jane Errington, a historian over at Royal Military College – they of the old school base ball. The book is well reviewed here but, short form, it’s an interesting view of early Upper Canada (1790s to 1820s) based in large part by review of early newspapers. In it, Errington suggests something of a window between the end of the War of 1812 in 1815 and, a few years later, a clampdown in trade and other contacts with the US towards the end of the decade. But even with her level of detail about the community, trade and industry, there is not much about beer itself. Meaning I am left unsure if beer was being traded within months of the end of a war, perhaps as a stop gap until local product restarted… if it was interrupted by the war… which is another question.

So, I was very happy to read in the comments that Steve Gates has published his history of brewing in the city and in the region. I couldn’t get out of the door to go get a copy but will tomorrow. Hopefully it will shed some light on what Robinson and Gillespie were up to.

[Original comments…]

Ethan – October 24, 2011 12:52 AM

http://communitybeerworks.com

I know why: because rye is the most awesome adjunct you can supplement barley with, ever. (iomo, that is.)

Craig – October 24, 2011 8:41 AM

http://drinkdrank1.blogspot.com/

Beer may have been used to denote that it was more heavily hopped. Also, and this is pure speculation, Smith may have changed his advertising from “beer” to “strong beer” to differentiate it as full strength beer versus table beer. “Beer” as advertised might not have been selling that well, so the old switch-a-roo may have been needed.

As far as the rye and oats go, Kingstonian brewers would have been subject to the same taxation and excise limitations, as brewers in the UK would have been. Both rye and oats would have been considered adjuncts, in beer at least, and therefore considered a no-no—correct?

Gary Gillman – October 24, 2011 9:39 AM

We would need to know whether the law at the time in Upper Canada prevented use of grain adjuncts in brewing beer. If it did not, this might indicate rye was sometimes used in brewing. So was oats and peas, historically all these received occasional use in the mash tun until English law tightened the definition of what could go in.

Another possibility: this brewer was also distilling and wanted rye and oats for that (not sure about peas but maybe they went in, too). Even if he didn’t distill, he might have had a milling operation and sold raw rye to nearby distillers.

Gary

Gary Gillman – October 24, 2011 4:20 PM

Incidentally Alan, that thesis of Jane Errington is one I find persuasive. The narrative has tended to go the other way in recent decades, but even without reading what sounds like a fine book, I think she is right. English Canada in large part was founded by former Americans, it is as simple as that. They weren’t the only ones but they had a founding and very important role as you know in Ontario and parts of Quebec and The Maritimes. To complement this but at a different stage (later 1800’s), parts of Canada’s West also underwent significant U.S. influence via immigration and for other reasons.

Royalist or not, the UEL had to share broadly the values and general ethos of the people who latterly were their literal neighbors. I think too what drove people to leave was in many cases more practical economics than anything else – those who had property to compensate found one outlet in Canada, i.e., it was easier to come here and start anew with property granted by the Crown rather than make claims in the States. I understand many Americans who stayed in the U.S. after the Revolutionary War did still sue the Crown. Many obtained compensation or a settlement. But clearly, that would have been a harder row to sow than to come to a place, not all that far away, where land was offered for immediate settlement and development.

I’ve always felt this is why Canada and the U.S., despite the 1812 War, fought numerous subsequent wars together or under some conditions of mutual support, any why our economies are so interlinked. It’s a voluntary thing, in other words. I don’t see it the way Pierre Trudeau did with his when-the-elephant-moves-we-feel-it analogy and I think that reflected some particular factors of his Quebec background.

Had we wished, we could have found a way to remain more independent of America, but we chose not to because we see so many things in common with Americans. We are both North Americans, in a word. This is not to suggest Canada’s identity is not distinct, of course it is, but as a regional North American characteristic, just as the U.S.’s identity and that of its sub-regions are regional examples of a North American identity. The countries will always in my view and should remain politically separate, but the many close economic and cultural ties testify in large part I think to the fact that the UEL were and therefore remained American in outlook and (non-political) identity.

And so coming back to beer and drink, we drink basically similar kinds, despite some differences before the craft era (largely effaced in the last 30 years). Our whiskies are less different than they may seem at first blush: both are made from varying mixtures of barley, corn and wheat. We are both big burger fans, football fans, baseball fans, and hockey fans – in the latter the influence has gone more the other way as it sometimes does. And as for basketball, a Canadian invented it – at a U.S. university, right? Sure there are some differences but those reflect more regional (to North America) characteristics than anything else, I’d argue. Thanks for the chance to enter these parenthetical points but I followed the link you gave to the review of her book and couldn’t forbear.

Gary

Gary Gillman – October 24, 2011 4:24 PM

For whiskey, I meant both countries distill their national spirit from mixtures of barley, corn and rye – wheat too in some cases.

Gray

Alan – October 24, 2011 4:47 PM

Not parenthetical at all as I think it goes to the heart of my idea that CNY beer moved here with the people just as much as the British carried their tastes here, too. Errington goes into a bit of the tensions between Kingston and York pre-1812 that were based on the cultural distinctions. I just bought a copy of “The Breweries of Kingston and St. Lawrence Valley” which I am hoping will have more tidbits on these things.

Gary Gillman – October 24, 2011 10:59 PM

Alan, thanks. Just a further point, since I like to be as accurate as I can. In reading up on Loylaist compensation after the Revolutionary War, it appears that the Commission set up to hear claims heard them from Loyalists who fled: I can’t substantiate that it heard them from Loyalists who remained in America and became U.S. citizens. Still, compensation was ultimately paid by the U.K. Parliament to many who submitted claims to the Loyalist Claims Commission. My point is, Loyalists who had been dispossessed of their property by the States (to finance the war) did sometimes obtain recompense, either by way of land in Canada or other compensation, and in some cases they got their lands back in the U.S., which assisted some to return. Not to minimize certainly the great travail many went through, especially those who migrated to Nova Scotia, but still I feel that their American character was not so easily shed, nor (in consequence) has Canada been able to do so.

Gary

Alan – October 24, 2011 11:07 PM

Oh, I agree. And the US compensated their own as well. A while ago, I found out that a bit of Ohio was first settled by revolutionary Nova Scotians.

Craig – October 25, 2011 11:16 AM

http://drinkdrank1.blogspot.com/

I was going back through the brewer’s testimony from the 1835 NYS Senate hearing. A NYC brewer, “of strong beer” by the name of Thomas Kelly is noted by the Comissioner of Deeds for the County of New York as not being a brewer of ale or porter—but of beer.

So, in 1835 New York City at least, ale and beer are considered separate things. His testimony is here

Gary Gillman – October 25, 2011 11:51 AM

It’s also the time of year of the advertisement, December-January. This suggests to me that the brewings, whether local or somewhere in NY, were seasonal brewing (October/November) and thus made to last a year at least, i.e., strong October beer. Beer brewed earlier in the fall advertised as beer “tout court” may have been designed for current consumption. I think in general, what this shows is the survival in Canada of products from the English tradition that had transplanted from the U.S. The local garrison’s didn’t need that as an excuse for English beer tastes, they got that direct from England and Scotland, but the one reinforced the other. All this is before the wave of lager-brewing of course in both countries.

The whiskey history is quite similar: Canadian rye whisky appears to be a version of U.S. straight rye, adapted by Loyalists who knew the drink in the old country in other words. Here the U.S. links seem quite evident since whisky in Scotland and Ireland (and England where there was distilling of whisky at the time) barley was the base of thr drink. Rye and corn are U.S. hallmarks of whisky and they became Canadian ones, too.

Gary

Alan – October 25, 2011 12:10 PM

But what are those two things? That is what I don’t get in the 1780 to 1840 (and lager) context.

Gary: 1815 to 1820 was a time of lesser British presence in Kingston and there were still a majority of American Loyalist in the community. There are a number of “old countries” at play.

Gary Gillman – October 25, 2011 12:58 PM

That’s what I’m saying, Alan. In the case of whiskey, the American mash bill, and taste to a degree, dominated and became permanent in Canada. Barley-based whiskey just didn’t happen in Canada even though dominant in the U.K. and Ireland.

In beer, there was less of a problem since the ultimate traditions were the same: the English soldiers and merchants liked beer, ale and porter; the American incomers liked the same, since this had transplanted to America from England earlier.

The real split came with lager, which Canada did take to ultimately, but more slowly than in America. But this is ahead of the period we are discussing.

Gary

N.B. Beer was probably more hopped than ale even by this time, but terminology was surely becoming indistinct as in England.

Steve Gates – October 28, 2011 12:50 AM

The reason why Robinson and Gillespie solicited rye was because of its prevalence in the Kingston area. Distilling was always king, there were a least a half dozen distillers for every brewer and the farmers cultivated what they knew they could sell. It was not until local brewers such as Morton who held sway with the farmer and persuaded them to switch crops to that of barley. Rye was being solicited because there was a plentitude of it locally and it would be suitable for brewing as well in a minimized introduction to the process. Oats and peas were being solicited simply because it too was bountiful locally and it would be purchased wholesale and sold retail. Gillespie in a former life was a general retailer specializing in locally grown vegetables, fruits amd dairy products such as cheese and butter. Oats would also be useful when feeding their horses used on the brewery premises. The solicitation for these items are unique in the Kingston area, I have not found anything like it in other examples of the early local brewery adverts.