This is maybe my hobby interest in this hobby of mine – brewers growing their own barley. This time its in Saskatchewan:

They wanted to go back to farming, too, and were able to buy back the original farm. Lawrence and his family live there today. Most farmers sell their grain wholesale, but the Warwaruks have figured out a smart, sustainable way to add value to the barley they grow. They do this on a much smaller acreage than the typical large-scale farming operation, where 3,000 acres is usually the minimum to make a profit on the wholesale grain market. The Warwaruks’ farm is just over 160 acres. All the barley grown on the farm is used for Farmery products. “If I was to take that barley to an elevator, I’m getting less than $3 a bushel, which is crazy,” says Lawrence.

What is the big deal? New York has farmhouse breweries all over the place. And I suppose that is right. And Lars is studying the farmhouse brewing traditions of Europe and particularly Scandinavia. It’s everywhere already, right? But in New York, a percentage of the hops and other ingredients must be grown or produced in New York State. Not all. And not all on that given farm. It’s a great program but it’s not all from one farm. And what Lars is exploring are really town and country brewing traditions – which is great. But it’s not what I am thinking about.

What I think the Warwaruks and my nearby neighbours the MacKinnons may have in common is that they are involved with (i) family grain operations, (ii) the are using brewing to create a premium value revenue stream to secure the farm from risk and (iii) they are not making overly wrought beers. This model may not scale. It may not ever extend beyond the local market. But it is intensely local. It is malt barley focused. It is also not the result of a funding or a research program. It’s utterly normal.

Any other examples out there? Girardin I suppose.

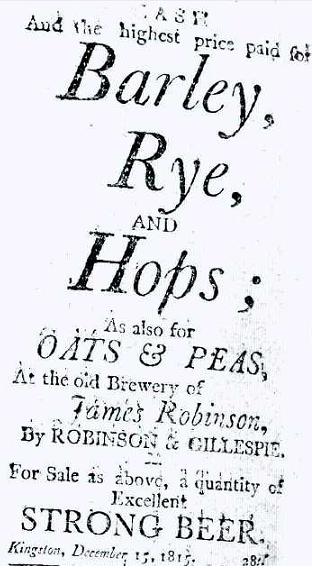

The ad is from

The ad is from