Jeff wrote an article for All About Beer this week called “Why Beer Experts Matter”. I commented by Twitter that it set out a “good argument by @Beervana but expertise is key, not the “experts” – personifying a body of knowledge just limits it.” Discussion ensued. I meant it. Good. It was not snide code. It good – and good can be, you know, good. And it got me thinking about experts, expertise, professionalism, experience and interest… and interests while we are at it. And Lars asked for more detail. So, In this post, I am going to try to explain myself to myself, Jeff, Lars and to you if you care to follow along. It is, however, not mandatory reading, there will not be a test and it is Saturday.

Jeff wrote an article for All About Beer this week called “Why Beer Experts Matter”. I commented by Twitter that it set out a “good argument by @Beervana but expertise is key, not the “experts” – personifying a body of knowledge just limits it.” Discussion ensued. I meant it. Good. It was not snide code. It good – and good can be, you know, good. And it got me thinking about experts, expertise, professionalism, experience and interest… and interests while we are at it. And Lars asked for more detail. So, In this post, I am going to try to explain myself to myself, Jeff, Lars and to you if you care to follow along. It is, however, not mandatory reading, there will not be a test and it is Saturday.

Let’s think about what these words mean: experts, expertise, professionalism, experience, interest and interests. One way or another they are all about being clever. Having amassed a body of information. But then they represent doing different things with that information. It is interesting to separate the threads to discuss each but it is really important to keep in mind how much they overlap. Things like this are not neat and tidy. That being said, let’s have a look:

Professional: A professional is not someone paid to do something. A professional is someone whose opinion you can act upon as presented without interpretation. Lawyers, accountants and doctors are professionals. Engineers, too. They… we… carry errors and omissions insurance in case our opinions are wrong and cause harm to those who relied upon them. It is not to say that that those who are not professionals are highly skilled or deserving of significant pots of money. But every time I hear someone mention professional baseball players, I ask myself where fans can file the claim against the Chicago Cubs for undue emotional reliance. Similarly, I can’t see any brewers getting errors and omissions insurance to protect drinkers against negligent brewing, especially given the amount of that going around. Are there beer professionals? Not that many. Not most of the folk you might hear calling themselves professionals.

Expert: Not all professionals are experts and not all experts are professionals. As a professional lawyer, I hire experts and I challenge experts – both pros and not pros. People don’t like us for that. Lawyers don’t really care. It’s the job. No, it’s the profession. Me, I have done enough work in certain specific areas like history and heritage related matters that I peer review the work of experts myself. I challenge the content of their reports. Even reports by experts who are professionals which I am supposedly not required to go behind. Thankfully, it happens rarely. Mainly because (i) professionals who are not experts in a given field should be aware of their incapacity and do not tread beyond their specialty and (ii) true experts are so focused on the particulars of their particular topic. Because experts are experts in niche topics. Can there be a beer experts? Not in my opinion. Because, for one thing, “beer” is too big a topic and, for another, so much about beer and brewing is so self-evidently shallowly researched. So far. Example. Stan asked where Cicerones fit in. I responded that it was an example of “expert creep – trained as top notch wait staff they take on more status.” I should have written “some” take on more status. The niche training works in the niche. Beyond the niche… well, things get wonky.

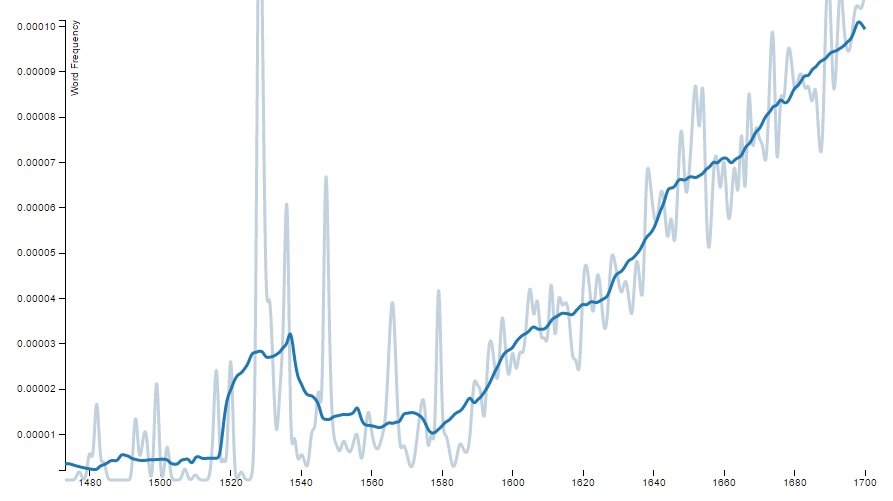

Expertise: This I think is the most important point. The body of knowledge is collectively the “expertise” in that topic. It also means the skill of an expert. I am interested in the first meaning. “Canada’s expertise in coconut production is lacking” is something that can be said. Similarly, we can correctly say that the western worlds collective expertise in all aspects of beer and brewing is not as sophisticated as its collective expertise in public health or the economics of international trade. Beer and brewing is (i) not as complex topic to attract a body of expertise and (ii) where it is complex it is not well researched… yet. There are reasons for this lack of complexity that are obvious. It is only beer. But there are also reasons for the lack of detailed study that are not as obvious. I call these factors “interests” and they are not all alike.

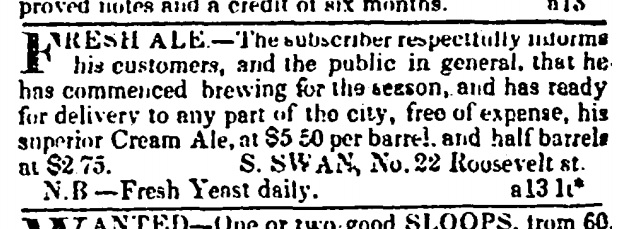

Interests #1: This is where things get truly odd with beer. Dr. Johnson in the 1700s once stated, “We are not here to sell a parcel of boilers and vats, but the potentiality of growing rich beyond the dreams of avarice.” He was an executor of the brewer Henry Thrale and spoke the truth. There is a lot of money in beer. Micro and craft brewers work incredibly hard to avoid discussing that. In 2007, it was so shocking to point this out that one risked a playground pile on and perhaps a cherry belly, too. Many excellent points were made. Tomme Arthur and other brewers chimed in mainly defending price inflation. I think that time has passed. We are more realistic about brewers as Andy’s recent article about Jim Koch and the reaction showed. We are no longer “all in it together.” Financial interests are exposed and being discussed. Which is good. Many beer fans won’t be taken as suckers any more. AND brewers will be able to describe the well deserved rewards for their efforts… even if a well informed consumer base means the less than realistic brewers out there may end up paying for their own experiments and self-assigned artistic status from their own pocket, not mine. Money is good but we all benefit from real information as much as we want honest beer at an honest price.

Interests #2: There are other sorts of interests at play which put pressure on access to real information about the beer we like. In my 12 years of writing about beer nothing as stupid has ever been written as the article from 2009 “Sober Thoughts On Writing About Beer” in which it was suggested that fewer people ought to be writing about beer. I reacted strongly. I won’t repeat the discussion but point out that while Jeff did not say the same think, he could be taken for being in the same neighbourhood when he argued “[w]hy should you bother seeking out an expert? Because beer experts do some things even 900 laymen together can’t.” What he was not saying, however, is that the 900 lay folk should shut up. He made a different argument. But I still think it was flawed for the reasons about seeing as he based much of the argument on this idea he wrote “[a] good expert opinion will draw on several threads of information—science, process, history and culture—and bring all of that knowledge to the discussion of a beer.” The trouble is not the validity of the idea itself but its applicability. For two reasons: (i) the science, process, history and culture of beer is not yet well studied and (ii) those holding themselves out as experts in beer generally have self-evident disinterest and even disdain for knowledge about “science, process, history and culture of beer” not to mention the economics of it, the health implications of it, public policy related to it etc. These are the people who might tell you all English beer was smoky before the use of coke in beer. They say so because they have not bothered to do two hours of studying. We need to be honest. There is much greater interest in protecting the status of expert in many of those who suggest they or others are experts than there is an interest in gathering and building the collective expertise. Beer is money. And the shallow PR wading pond needs to be fed. But note I said “many”. To be abundantly clear, if I am looking for information about current trends in the global beer retail market, I seek out Mr. Beaumont‘s opinion. If I want to know as much as I can know about hops, I ask Stan. There are others with that sort of focused understanding who have not only earned but absolutely resonate with the necessarily broad, deep and detailed awareness to be respected as experts in their field. And each of these guys would also guide me and you to others of whom they might say are the expert’s experts. I would estimate them to total about 10% of those who have an interest in you thinking they are beer experts. Sorry to break the news.

Interest: we all have an interest in beer. I would not be writing on this keyboard if I did not. I would not be sketching out a number of alternative choices fourth book on beer if I did not. Everyone who wants to experience a greater variety of the deliciousness of beer, the exquisite comfort of pubs or the vast and particular history of brewing through time has an interest. It is lovely. It is worth doing. It’s participating in part of a bigger thing across culture and centuries. But the beer itself is experienced one person and one beer at a time. Beer is experienced only in the theatre of the mouth. With time and practice, anyone can hone their skills and create a deep body of experience which gives them greater and greater pleasure. Along with this they can write reviews of the beers they taste, write blog posts about the themes they see developing and a few can be lucky enough to be asked to write articles and books. Which leads to requests to be quoted. And called an expert. Hmm. It also leads to cherry syrup laced, bourbon barrel aged, sea salt infused gose. Which sucks. But the “expert” told you you should like it… except you just don’t understand. Sadly, you buy it and drink it and feel bad about yourself for (i) being not smart enough and (ii) having that crap in your mouth and (iii) having just dropped ten bucks to affirm you are not smart and to place crap in your mouth. This is a terrible thing for one simple reason. Beer should make you happy.

So you see how this works? It all relates the thoughts of Ivan Illich in fact. And do you see what I just did? I made you feel odd about the whole Ivan Illich thing. I just experted on you. I didn’t mean to. Sorry. This essay is in no way intended to be a sword of Zorro moment, a triumphal flourish in which the topic is summed up so completely you need not think further. That is not my point. I only propose the above. It is just something I have been thinking about. If I took more time, I would weave in more links with illustrations of the points I may be making. I’d add in Andy’s discussion here. But I didn’t. This is not a professional opinion. It’s not the statement of an expert. It’s just something I have an interest in triggered by the excellent thoughts of Jeff and Lars related to one corner of the whole body of knowledge related to beer and brewing.

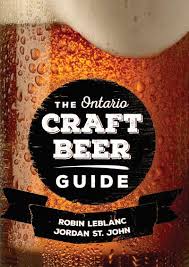

I have been remiss. Well, late. Not lazy. Late. Distracted? Distracted. Jordan and Robin sent me a digital copy of this book weeks ago and I have only gotten to writing my review now. There’s been taxes to do at the last minute. Children to take to sports or hover over as math gets the best effort we can expect. Evenings like tonight at City Hall giving my best advice to council. I got a hair cut Sunday. At 11 am if you are wondering. But all the while I have kept dipping into this book. I like this book. I like this book for a few reasons. Let’s be honest. I have secondary skin in the game. I co-wrote the history of Ontario beer with Jordan. It’d be nice to think that everyone who buys this book might buy our book, too. But that’s not why I like this book. I like this book because this is the book that got me interested in the beer over the next horizon over a decade ago.

I have been remiss. Well, late. Not lazy. Late. Distracted? Distracted. Jordan and Robin sent me a digital copy of this book weeks ago and I have only gotten to writing my review now. There’s been taxes to do at the last minute. Children to take to sports or hover over as math gets the best effort we can expect. Evenings like tonight at City Hall giving my best advice to council. I got a hair cut Sunday. At 11 am if you are wondering. But all the while I have kept dipping into this book. I like this book. I like this book for a few reasons. Let’s be honest. I have secondary skin in the game. I co-wrote the history of Ontario beer with Jordan. It’d be nice to think that everyone who buys this book might buy our book, too. But that’s not why I like this book. I like this book because this is the book that got me interested in the beer over the next horizon over a decade ago.

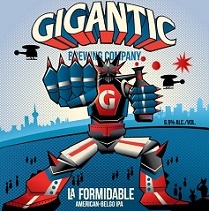

This is the point where I claim purity. Fully. Fundamentally. Every good beer blogger knows the line. I may have received these gifts by FedEx but, as with Christ’s beneficence offered through the holy sacrament of communion, I approach each chalice with pure intent and leave fully pardoned. To celebrate this, I am sipping a glass of La Formidable, a juicy 6.9% beer recently couriered to my house by

This is the point where I claim purity. Fully. Fundamentally. Every good beer blogger knows the line. I may have received these gifts by FedEx but, as with Christ’s beneficence offered through the holy sacrament of communion, I approach each chalice with pure intent and leave fully pardoned. To celebrate this, I am sipping a glass of La Formidable, a juicy 6.9% beer recently couriered to my house by