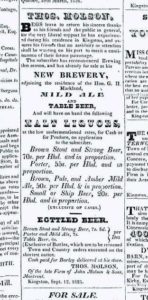

Click on that image to the right to revel in its full glory. That is an ad for the new brewery opened in my town in 1825 by Thomas Molson seeking to break out of the decades old family business down the river in Montreal. A neat if short lived enterprise. But I speak not so much of Tom or his ambitions today as the evidence in that ad of the marketplace of ideas into which he was speaking. It ran in the Kingston Chronically for for many months so it was speaking to somebody.

Click on that image to the right to revel in its full glory. That is an ad for the new brewery opened in my town in 1825 by Thomas Molson seeking to break out of the decades old family business down the river in Montreal. A neat if short lived enterprise. But I speak not so much of Tom or his ambitions today as the evidence in that ad of the marketplace of ideas into which he was speaking. It ran in the Kingston Chronically for for many months so it was speaking to somebody.

Notice all the sorts of beer. As this is 30 years after the earliest reference to porter being downed in Upper Canada, I am not surprised to see it on offer. On my reading of the ad, however, I see the brewery knocking out eight sorts of beer. There are five price ranges. There are wholesale and retail sales. At the bottom you can see they are buying barley which means they are, as would be expected for the times, malting their own malt. So it is likely the amber beer is made of amber malt and the brown stout is a whopping big beer made of brown malt. Now, that’s a beer to recreate.

Notice also that he will take produce or cash. Somewhere I came across an article from a few years earlier about another Kingston brewer agitating for the buying of local beer over the New York stuff. I need to dig that out. Albany made beer showed up not long after the War of 1812 ended. But by 1825, Upper Canada is well into its anti-American most conservative phase under the grip of what was known as the Family Compact. The first wave of leadership from the American Loyalist refugee group that showed up in the 1780’s after the American Revolution was lost is dying off and is passing control to British born Tories who came of age in the glory of the defeat of Napoleon. They are seeking to make Upper Canada a model colonial example to the Georgian Empire under, of course, their guiding hand.

What is really most interesting to me, that all being said, is that there were other brewers in town. With their own brands of beer. Could it be that the beer fan of 188 years ago had his or her choice of over twenty beers? Did they buy based on preferences within a wide selection? That for me would be quite, as they say, a something.

That is Alcohol and its Role in the Evolution of Human Society by Ian S. Hornsey. I had no idea. In a work of beer writing that is still trying to find its way, seeking to evolve from fanboy gushing or trade focused boosterism or underdeveloped efforts at business journalism, Hornsey’s 2004 book

That is Alcohol and its Role in the Evolution of Human Society by Ian S. Hornsey. I had no idea. In a work of beer writing that is still trying to find its way, seeking to evolve from fanboy gushing or trade focused boosterism or underdeveloped efforts at business journalism, Hornsey’s 2004 book