I am a huge fan of the not blog Forgotten New York and its regular and comprehensive investigations of some aspect or another of New York’s architectural heritage. This week we have a study on some of the oldest bars in New York City.

Category: 2000-05

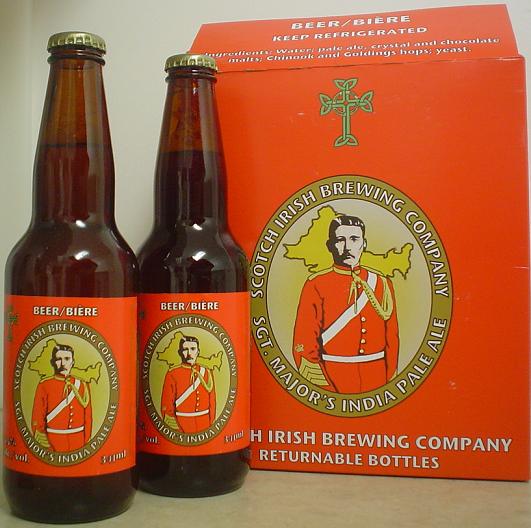

National Six-Pack X: Sgt. Major’s IPA, Scotch Irish, Ontario

Finally the wee truck from Fitzroy Harbour up on the Ottawa River near Arnprior made its way down to Kingston giving us a taste of this excellent local ale. This is a hoppy beer that reminds me a lot of my recollection of the Dragon’s Breath Ale contract brewed and bottled by the old Hart Brewery of Carleton place about (without looking) 35 miles south of Fitzroy Harbour. Candy cane Goldings and grapefruity Chinook hops combine to provide quite a bit of a sour tang to this fairly lightly bodied clean ale. The finish is a nice combination of the slight rough edge of the hops and the light graininess of the pale ale.

The brewery has a pretty good web presence which provides the names of bars where you can buy a pint of tap. It also describes the Sgt. Major IPA as follows:

Our Sgt. Major’s IPA is our most intense ale to date. It’s a massively hoppy and quite bitter beer, yet one with a nice, full-bodied malt background. It weighs in at 5.5 percent Alcohol (balanced by its big body). It is hopped with lots of Chinook hops which impart a tasty white-grapefruit/spice/resin flavour and aroma (and a total of 68 IBU) making the ale wonderfully refreshing. Being at the low end of the alcohol range for the style, it’s as close to a supping pint as tradition allows. While the Sgt. Major’s rather considerable bitterness is nicely balanced by its full-bodied maltiness, this is overall a predominantly hoppy ale. The full body of our India Pale Ale comes from lots of English pale ale malt and crystal malt, with a very small amount of chocolate malt. Our all-natural draught ale uses no artificial additives or preservatives.

I don’t know if that means the bottled version does have artificial additives and preservatives. I would also think that the full-bodied characterization is pushing it a bit in a world where a drive as far south as this is north will get me a Middle Ages Wailing Wench or Druid Fluid. It is, for example, lighter but hopper than Propeller’s ESB from Halifax, one of the nicer bodied ales in Canada, but according to the standard scheme of bitters and pale ales a grade below an IPA. But this all is not to distract from the ale, just the adjectives. Like Mill Street Tankhouse Ale, the lighter mouthfeel I think reflects the apparent or possibly emerging Canadian style of pale ale, as opposed to my suggested putative style sweeter fuller Canadian amber but less hoppy. Both are a degree or two off the standard for an American pale ale or its amber sibling and different again from English ones.

Nevertheless, this is very good beer and a worthy addition to quest for the National Six-Pack. The quality of the craftsmanship makes me think a wee trip to the Manx in Ottawa is in order to try out the brewer’s draught only Session Ale, a rare ordinary bitter which – if true to style – should not hit 3.5% and ought to be as refreshingly quaffable as a good dark mild.

New York: 46’er Pale Ale, Lake Placid Craft Brewing, Plattsburg

I bought at six of this beer in Hannaford’s grocery store in Watertown, New York for $7.99. Customsman let it go. Declared but he no cared. It would be sweeter for that bonus but could it be? I really like this brew. Medium body. Lots of green hops almost to the point there is a green pea, mint and orange peel thing happening.  Under that some crystal malt sweet and nice grainy pale malt. Some pear juice among the grain in the finish. Quality from the north country and just over the border. More as I think about it. Top cap design.

Under that some crystal malt sweet and nice grainy pale malt. Some pear juice among the grain in the finish. Quality from the north country and just over the border. More as I think about it. Top cap design.

The next day: Lake Placid Craft Bewing is not in Lake Placid though it used to be. The brewery explains:

Founded in 1996, The Lake Placid Pub & Brewery began as a small brewpub, brewing less than 400 barrels each year for sale on site. Our great-tasting, fresh beer quickly grew in popularity and requests for our products poured in from area restaurant and bar owners. Production increased exponentially to keep up with demand, and we sold every last drop of beer we produced. In November 2001, the LPP&B; expanded to a second brewing facility in Plattsburgh, New York, known as The Lake Placid Craft Brewing Company, quadrupling our brewing capacity and adding bottles to our product lineup.

That is a success of scale and smart growth – and when it is on the Hannaford’s in Watertown shelf 200 miles west as well as on tap at the Blue Tusk (look far right) 350 miles south west, Lake Placid is making a mark for itself. They are smart, too, in keeping it to two bottlings this pale ale and the heavier, maltier Ubu ale which I brought back way back last spring. Just so you know, the pale ale comes in at 6% with the Ubu at 7%. My man Lew Bryson tells me they have a milk stout on tap at the brew pub as well as an even hoppier Frostbite Pale Ale. He also says:

A “46’er” is someone who’s climbed all forty-six “high peaks” of the Adirondacks..

I really do not understand the experience of the lower end of the beer advocate scale. Maybe they all had shelf stung bottles. Mine are definately fresh and displaying nothing other than loveliness. I would like to do a side by side with some Southern Tier IPA, maybe a Ithaca Flower Power and even a Syracuse Pale Ale to get some sense of the Lake Erie, Finger Lakes to Lake Champlain brewing arcing axis and what it all means.

The Blue Tusk, Syracuse, New York

The last of what Lew Bryson has called “the triumvirate” of Syracuse’s temples to ale, the Blue Tusk, was my favorite for the mood of the day. Much Middle Ages on tap as well as Stone and Victory and even Blue Lite for who knows why. Loud and chatty, we walked in and immediately got into a two and a half hour conversation about Canadian and American differences with a couple of chemical engineers who were regulars. SU had just won a basketball game at the Dome and the place and the streets were loaded with fully grown men dressed in orange. The staff were happy to please and, though busy, a pleasure. One thing I liked is that the place smelled like beer. Not fried food and not smoke.

The real surprise of the night was the Syracuse Pale Ale on tap, a revelation of simplicity and quality over complexity and gimmick. If I had one beef it was the understocking of lower alcohol styles. There are some great milds and ordinary bitters out there and, unless you are aiming at getting plastered, a session of 8% to 10% beers is a bit much. Even with that being said, as with Clark’s, the Blue Tusk is all about the quality and handling of real ale but with the hubbub that you sometimes want with your brew.

Awful Al’s, Syracuse, New York

We only stopped in Awful Al’s briefly when walking between Clark’s and the Blue Tusk. Two reasons. I was told to stop taking photos and it is a reminder of how great the anti-smoking laws are for the consumption of fine beers. It is, however, the dimmest lit bar I think I have ever been in and as a result the doctored photos give you the sense of the place as cross between photographer’s dark room, a 1970s era Soviet submarine and a very merry upper level of Hell.

Awful Al’s is the place to go for whiskeys and bottled beers. They have a very good selection and a hip atmosphere and clientele. It’s a bit of a meat market, so be warned – it can be very crowded and is filled with the yuppies that you didn’t find at Clark’s. But if you are looking for a dram of Balvenie PortWood or a Laphroaig, this is your place. It’s also the only place I know of in Syracuse that have a waiver from the smoking ban in bars and restaurants – it’s very smoky as a result.

Very smoky as the streets by dark industrial mills at midnight in 1840 were smoky. The ever excellent Lew Bryson is warmer to this particular flame to the moth in his ever informing book New York Breweries (1st ed, p. 205):

…walk over to Awful Al’s Whiskey and Cigar Bar (321 South Clinton Street, 315-472-4427), across from the Suds Factory and lose yourself in contemplation of hundreds of bottles of spirits. Come back to your senses and realize there are some great taps of beer here as well, a big old humidor, and big couches and armchairs to relax in while you enjoy your smoke whiskey. This is civilization….

So in the end I did not have a dram or a drop in Awful Al’s, driven by oxygen deficit syndrome as well as my fear of such a complete temple to appetite and someone’s reasonable sensitivity to having your face on the internet. I think that I would have to get to know it better, drop the residual asthma and have a change of clothes so that I could burn the nicotine soaked ones I would be leaving in. And buy those spy camera glasses everyone is talking about. But that is just me. Every heaven is not the same heaven and you might like Lou’s better than mine. I know I found mine at the Blue Tusk which I will report on anon.

It is, in reflection, interesting that Al’s, Clarks, the Blue Tusk and even the hotel bar at the Marx where we stayed each suited a different definition of comfort-and-joy and God-rest-ye-merry-gentlemanliness. All distinct from the Maritime and New England taverns of benches and heavy wood tables like those of Halifax or Portland Maine’s Gritty McDuff’s and Three Dollar Dooies, again, despite the shared goal. Speaks to the differences in local culture as much as anything I suppose.

Clark’s Ale House, Syracuse, New York

I came away from a visit to Clark’s Ale House knowing I should visit it again in a different circumstance. In the middle of a semi-sub-roaring tour of the town with friends, the quiet of Clark’s was a little disconcerting and, given a wrong moment, felt like pretense…but I figure it was me. It has no TV, no music, no bellowing bartendings shouting to be heard. It is also smaller than I had expected with a few tables up on a second level above the bar.

Clark’s famous roast beef sandwich on an onion bun. Dapper gents neatly sliced beef and pulled pints behind the bar. I had an excellent Armory Ale, a Middle Ages brew only available at Clark’s. Every brew I’ve had from Middle Ages is so well done, I should have expected this American pale ale to be as good as it was but well-made and well-handled beers are actually so rare that you have to note when you are in their presence.

The reviewers over at the Beer Advocate are far more certain and with a return visit maybe on a Sunday afternoon as opposed to after the game on Saturday night I would also write as does one from Michigan:

From the outside Clark’s is mighty inviting when your walking about the streets of downtown Syracuse on a biting cold late Autumn evening. You can see the jovial patrons, their heads reared back with laughter, through the large paned glass front. The warmth draws you in. The beer keeps you there. A pint of Middle Ages and a warm roast beef sandwich amid the chatter of beer lovers melts the icicles fixed to your eyebrows. Nifty layout holds pockets of seating, against the bar, under a window, in the back room with your best buddy, even an upper level I didn’t explore. Dark stained woods around and ivyed trellis above. Cozy.

Go to Clark’s and know a quiet night with their beers.

Ontario: Church-Key Brewing, Campbellford, Northumberland Co.

I got off the 401 at the Brighton exit and headed away from that town, going north. I will write more about this brewery tomorrow when I am not so tired but for now here are some pictures and the assurance that some of the best beer in Ontario is being made in a small Victorian church in the rolling hills of Northumberland county. Just one point before tomorrow, however: there were renovations going on and that is why a good swiffering looks due.

The Next Day: You have to spend an hour getting to and from Church-Key Brewing from the 401. Do it. It sits between Campbellford and Springbrook on route #38 on a high point among small century farms. If it is not on the road, you will notice the yellow draft dispensing van out front. The brewery is housed in the former Zion United Church which was likely the former Zion Methodist Church. The main body of the building is from the 1860s or ’70s with an addition from the 1920s that the brewery is expanding into at the moment. Its 3000 litre conical fermenters stand floor to rafters like the dullest organ pipes in the what was the sanctuary.

I got to spend an hour with Church-Key Owner John Graham and Marketing Director Cary Tucker. We got so quickly into talking that I didn’t even sample any samples. They only sell six-packs at the brewery, moving kegs to bars and restaurants from Ottawa to Toronto, Kingston to Peterborough. Cary and I got into beer travelling, the joys of the Galeville Grocery and his website. These guys like to know what is going on in the industry and, after five years or operation, are still self-described beer nerds.

They brew a lager, a pale ale, a smoked ale and a chocolate porter and, going by the two sixes I picked up, the beer is some of the best made in the province. I’ll review the smoked ale and chocolate porter later but suffice it to say that I can easily see making the two and half hour round trip some Saturday just to get another fix. Recently, they have won some important awards:

Church-Key Brewing picked up three Gold Medals at the second annual Canadian Brewing Awards held at the Duke of Westminster Pub in Toronto. Church-Key’s first gold medal came in the Scotch Ale competition as Holy Smoke was chosen Best of Category. In the Cream Ale Category, Church-Key’s Northumberland Ale tied for the Gold Medal with Gulf Islands Salt Spring Golden Ale from British Columbia and Quebec’s Microbrasserie du Lievre La Montoise. Church-Key’s Decadent Chocolate Porter, flavored with cocoa from World’s Finest Chocolate in Campbellford, tied for Gold in the Stout or Porter category with Black Oak Nutcracker from Oakville, Ontario and Boreale Noire from Quebec.

Impressive competition which makes me think we have a couple of candidates for the National Six-Pack.

Vermont: Ravell Porter, Magic Hat, South Burlington

I had such high hopes for this post, comparing four of the brews in the South Burlington Vermont’s Magic Hat Winter mixed 12 pack. Then the holidays hit, then the guests arrived, then the defence of the bottles began. Right now I have maybe 30 singles of beer stuck away for later comment at a measured pace. Enough to get me into February easy – as long as I can keep the hands of others off of them. Eleven of the Magic Hats were sacrificed to that cause. All except one of their porters named Ravell.

I had such high hopes for this post, comparing four of the brews in the South Burlington Vermont’s Magic Hat Winter mixed 12 pack. Then the holidays hit, then the guests arrived, then the defence of the bottles began. Right now I have maybe 30 singles of beer stuck away for later comment at a measured pace. Enough to get me into February easy – as long as I can keep the hands of others off of them. Eleven of the Magic Hats were sacrificed to that cause. All except one of their porters named Ravell.

Porter has become one of my favorite styles, if only due to the uncertainly brewers have facing the problem of what it is supposed to taste like. Porter was one of the earliest industrial products and led to a capacity war from say 1790s to 1820s London which had a great effect on mass production of other goods as well as the local production of beer. By the mid-1800s, it had been replaced by other beers due to two discoveries – lagering and true pale malting. As always, when technologies change, tastes shift and the demand for this dark and sharp style faded to be replaced for a while by mild in England, followed by pale ales and then by the ubiquitous industrial lager-pop most drink today.

From my recollection of the others in the 12 pack, Magic Hat is a largely soft brewing firm. [Sleeman, by comparison, is a fairly hard brewing firm.] The yeast of the Ravell, sour and fruity, is in the front of the palate, framed by chocolate malt and then some hop bitterness. I would not call this a balanced or rich example of a porter but originally porters from what we know were not round and balanced. They should not be confused with nut brown ales anymore than with oatmeal stouts. They were from an era that saw brewing and storage occur in wood and that would impart sourness like we see today in many Belgian brews. Here are the stats on the brew from Magic Hat:

Our Odd Porter. A porter brewed with whole vanilla beans. Available whenever young William and father John deem it so.

Yeast: English Ale.

Malts: Pale, Crystal & Chocolate.

Hops: Warrior & Fuggles

Alcohol by Volume: 5.60%

Original Gravity: 1.056

Bitterness Units: 22

SRM: 63.6

The vanilla bean note is evident once noted but really creates as many issues as it resolves. It lies under the chocolate and hops bitterness and may feed the impression that the yeast is fruity. It is not, however, an overwhelmingly vanilla-esque ale. The effect is somewhat like the use of licorice in other dark ales, as in the Sinebrychoff Porter from Finland reviewed a few weeks ago. One beer advocatonian says it is too thin, which is fair comment.

Not the first porter I would grab but certainly worth discussing.

Irene’s, Bank St., Ottawa, Canada

Last night before going to see the Pixies, the siblings and I took advantage of the moment to visit an old friend, Irene’s pub in Ottawa’s Glebe district. Irene’s is a neighbourhood bar which means it is not necessarily the place to take someone on a first date unless you are on a serious testing night-out. If she agrees to go to Irene’s again, she wins. If she suggests going to Irene’s again, you win.

Last night before going to see the Pixies, the siblings and I took advantage of the moment to visit an old friend, Irene’s pub in Ottawa’s Glebe district. Irene’s is a neighbourhood bar which means it is not necessarily the place to take someone on a first date unless you are on a serious testing night-out. If she agrees to go to Irene’s again, she wins. If she suggests going to Irene’s again, you win.

Book Review: Terry Foster, Beer Writer

Terry Foster is one of my favorite beer writers and the most interesting thing about him as a beer writer these days is he does not have a website. I don’t know how you can exist without a website these days. How else will all the Google bots be able to share your daily musings. Google bots…bots…Google…[Ed.: Giving author a good shake] Oh, right…there is no money and no audience in a website and others are doing it already so why bother. Good point.

Terry Foster is one of my favorite beer writers and the most interesting thing about him as a beer writer these days is he does not have a website. I don’t know how you can exist without a website these days. How else will all the Google bots be able to share your daily musings. Google bots…bots…Google…[Ed.: Giving author a good shake] Oh, right…there is no money and no audience in a website and others are doing it already so why bother. Good point.

I encountered Terry Foster as a home brewer. He is the author titles #1 and #5 in the Classic Beer Style Series published by the Association of Brewers, a US company promoting the homebrew industry. Pale Ale is the first in the series and Poer the fifth. These books are now over a decade old but recently I noticed that Foster has been writing articles for Brew Your Own magazine regularly as well. These sorts of writings as well as my years of one hundred gallons of output have convinced me that the appreaciation of beer is uniquely advanced by learning about and undertaking its production.

A number of the early homebrewing authors started me on that path and it would be my suggestion that Terry Foster is a continuation of that line of thinkers and writers about beer. In April 1963, month of my birth, the British Government ended the taxation of homebrewing under the Inland Revenue Act of 1880 which required records to be kept and a one ound license to be paid. As W.H.T. Tayleur states in his text Home Brewing & Wine-Making (Penguin, 1973) at page 15:

This legislation reminaed in force for eighty-three years, but although at first many thousands of private brewing licences were taken out the number of home brewers steadily declined over the years until by the middle of this century, and after shortages of the necessary ingredients caused by two world wars, hardly any of the few that were left bothered to take out licences.

By removing the need to license, the government created an industry and changed brewing, to my mind, for two reasons. First, self-trained home brewers became self-trained micro-brewers as the opportunities to make money with the skill became apparent. Second, consumers gained access to well-made home brews which were much cheaper and much tastier than the standardized industrial kegged beer the 1960s were foisting upon people. Without men like the 1960s authors C.J.J. Berry and Ken Shales as well as David Line in the 1970s, all writing primarily through Amateur Winemaker Publications, many a brew-pub or craft brewery on both sides of the atlantic would simply not exist.

C.J.J. Berry, Ken Shales and David Line

Foster is perhaps the last of this tradition of British home brewing writers – and not just because his slicked back hair, styled in common cause with them. His two books, Pale Ale and Porter each provide a history of the style, a description of the elements, a guide to making them and a discussion of the commercial examples. Like those earlier authors he provides the context of the style and also deconstructs the mystery of how the brews can be made. Context and technique are two things modern industrial commercial brewers would like to shield from their customers – they more they were to know about what is out there and what it costs, the less likely the concept of brand loyalty might hold the customer.

Foster’s recent articles in Brew Your Own magazine continue this tradition. I have copies of the following articles:

“Pale Ale”, BYO September 2003, page 30.

“Old Ales”, BYO, September 2004, page 27.

“Anchors Away – A History of Malt Extract: Part 1”, BYO October 2004, page 30.

“Let’s Get Rid of the Water – A History of Malt Extract: Part 2”, BYO, November 2004, page 34.

As is the mandate of the magazine, Foster provides context and technique, showing how historical styles can be recreated with confidence. For example, in the third article he discusses how the British Navy invented malt extract in an effort to provide beer to sailors as a necessary food while in the fourth he describes how later extracts were used to avoid the stupidities of prohibition.

Foster’s style is attractive in that he is a plain speaker. In a world of where reputation and brand is all important, he can write of Yuengling’s Pottsville Porter:

…this is in some sense a classic porter, although it is bottom-fermented. Unfortunately, although it has many adherents, I am not one of them as I find it a little disappointing.

Not only is he not looking for the next PR opportunity when he writes, he is a bit folksy while also well researched. He is a trained chemist and has been a professional brewer for over 40 years, according to his BYO bio. He is interested and as a result interesting.