A rather swell personal essay about one man’s love of a beer in today’s Globe and Mail:

Then one weekend last spring I was told they were out of Export in six-packs. I tried again the next week. Same story. The third time, the guy they call Red shook his head and said, “Sorry, they are not making it in six-packs anymore. I guess the six-packs aren’t selling very well.” I ordered two six-packs of something else and made my way home. I think I left the store paraphrasing T.S. Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock in my mind, “I grow old, I grow old, I still like my beer cold.” I was brooding over whether to switch brands or throw away my aversion to drinks packaged in aluminum. Neither option appealed to a man set in his ways.

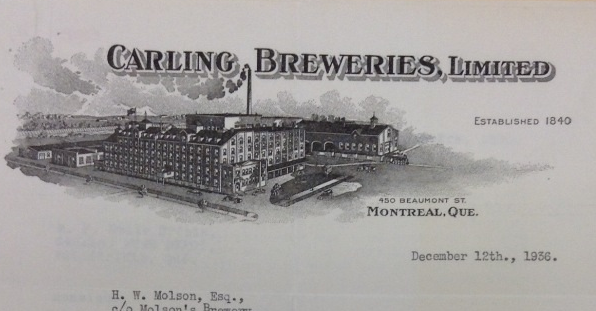

I think I am developing a soft spot for big industrial brewing. Maybe not like the guy in the essay but not so far off. See, I am hitting the mid-1900s in the Ontario brewing history that I am writing with Jordan. And I am writing today about how, as might be expected, EP Taylor looked out into the world at the outset of the 1950s and saw nothing but markets and opportunities. In 1952, he buys Quebec’s National Breweries, the company born of consolidations which had first inspired Taylor’s initial plans in 1928. In the same year, Carling Black Label was first brewed under contract in the United Kingdom. In the years that followed he expands operations in the US and buys breweries in Canada’s western provinces. Taking on the challenge, competitor Labatt bought breweries in Manitoba and British Columbia while building a new brewery in Montreal. Their original location in London Ontario also underwent large scale expansion. With the move by Molson into the Ontario market in 1955 with the building of new 300,000 barrel a year brewery on Totonto’s waterfront, the province’s big three brewers which would dominate the next thirty years were established. Whammo.

It’s all so positive and happy. Ontario’s population expands by 20% over the 1940s and the 1950s are pure economic boom. I may not want to drink the stuff that they are brewing but it’s all quite the rush.

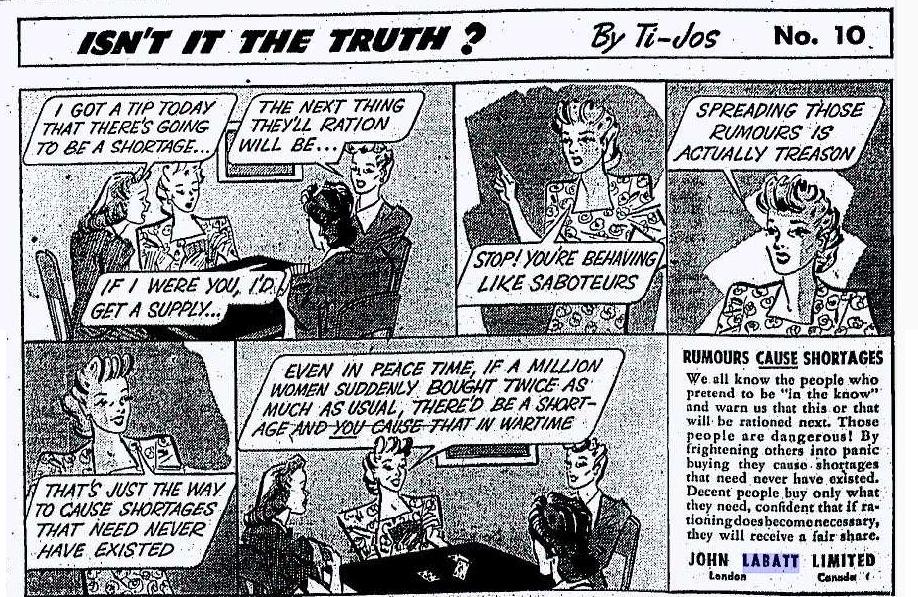

This in interesting… well, to me at least. It is from the

This in interesting… well, to me at least. It is from the