Home alone on a sick day, what else better to do but catch up with my old pal Pehr Kalm on his travels 264 years ago. Working on the Ontario beer history book in recent days, I am looking for references to brewing in New France to seek if I can established what might have been going on around here before it was even Upper Canada. See, what is now Ontario has been many things in the past, bits and pieces of many empires. Beer and other drinks hitch a ride with most of them. And until 1791, southern Ontario was part of the British colonial Province of Quebec and, before 1758-60, part of New France.

Home alone on a sick day, what else better to do but catch up with my old pal Pehr Kalm on his travels 264 years ago. Working on the Ontario beer history book in recent days, I am looking for references to brewing in New France to seek if I can established what might have been going on around here before it was even Upper Canada. See, what is now Ontario has been many things in the past, bits and pieces of many empires. Beer and other drinks hitch a ride with most of them. And until 1791, southern Ontario was part of the British colonial Province of Quebec and, before 1758-60, part of New France.

And we have some really swell tidbits of information. On 15 August 1749, Swedish botanist and diarist Pehr Kalm was at a reception for the newly arrived Governor General of New France, the Marquis de la Jonquiere, where he reports the “entertainment lasted very long and was as elegant as the occasion required.” All the greatest and the good of the colony were there but you get the sense that it was a wee bit laddish as this is the main topic he records of the conversation:

Many of the gentlemen, present at the entertainment, asserted that the following expedient had been successfully employed to keep wine, beer, and water, cool during the summer. The wine, or other liquor, is bottled; the bottles are well corked, hung up in the air, and wrapped in wet clouts. This cools the wine in the bottles, notwithstanding it was quite warm before. After a little while the clouts are again made wet, with the coldest water that is to be had, and this is always continued. The wine, or other liquor, in the bottles is then always colder than the water with which the clouts are made wet. And though the bottles should be hung up in the sunshine, the above way of proceeding will always have the same effect.

I need to try that one. We have to remember that Kalm was not an idle wanderer. As the Borgstates, he “was commissioned by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to travel to the North American colonies and to bring back seeds and plants that might be useful to agriculture.” So, he is a scientist on the lookout for things… stuff… doings and goings-on.

He describes a pretty rich diet amongst the elite. Brandy, coffee and chocolate for breakfast. Red claret and spruce beer are in much use at the noontime dinner and again at supper at seven in the evening. He notes that people store their beer in their ice cellars beneath their houses to keep it cool in the summer and notes that it is customary to put ice in drinks to keep them cool. It is likely that the beer is spruce beer as “they make a kind of spruce beer of the top of the white fir” which is seldom taken by people of quality. He also notes that it is “not yet customary here to brew beer of malt” and also “nor do they sow much barley, except for the use of cattle.”

This last bit is interesting as one hundred years before the Jesuit records clearly show efforts to create local brewing capacity as part of the earlier economy of the colony. Kalm, however, describes a wealthier and less self-sufficient colony in the late 1740s at least among the elite. There is no longer a press so all books are imported from France. Large sums are spent on boat loads of wine. Cider and beer are so 1630s it would appear.

What does that mean for Ontario? Well, likely the forts by the end of the French empire were supplied with casks of wine rather than malt made beer. Yet, in the last quarter of the 1600s, that was not necessarily the case. When the likes of Lasalle and Frontenac ruled the spot where the Great Lakes meets the St. Lawrence River… who knows?

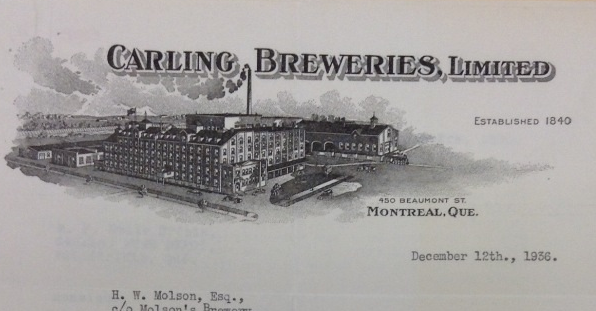

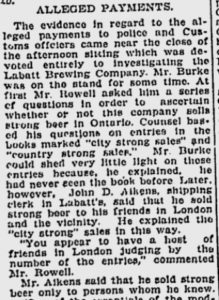

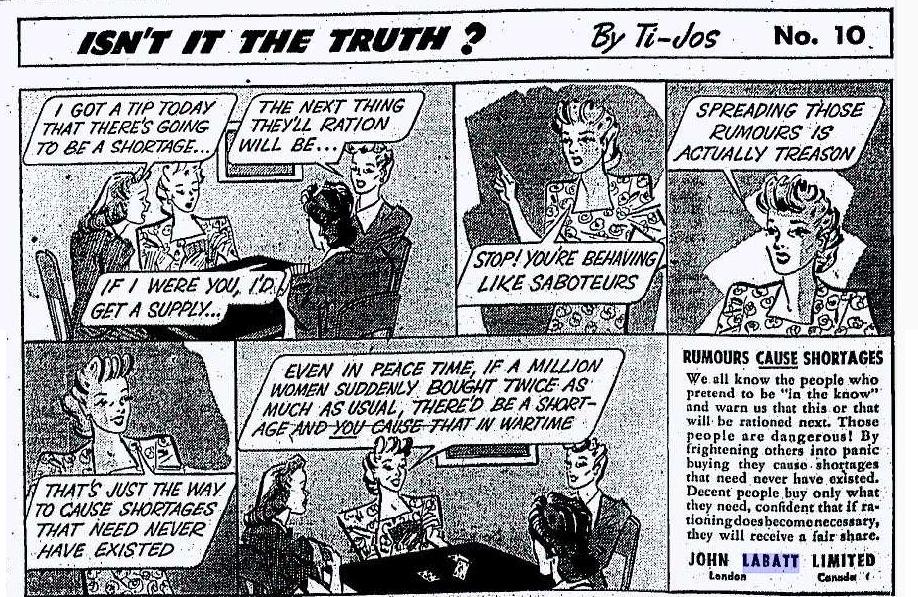

Coming to the end of the first draft of the Ontario beer history Jordan and I are writing, I find myself in the spring of 1927 at the Toronto hearings of the Federal Royal Commission on Customs and Excise. Officials from every major brewery in the province are being grilled under cross examination on their business smuggling beer into the United States. The glimpses of honesty through the lies are just good clean fun. When the manager of Carling was asked if they couldn’t make a profit at $1.75 a case, he replied “well, you can’t make a large profit.”

Coming to the end of the first draft of the Ontario beer history Jordan and I are writing, I find myself in the spring of 1927 at the Toronto hearings of the Federal Royal Commission on Customs and Excise. Officials from every major brewery in the province are being grilled under cross examination on their business smuggling beer into the United States. The glimpses of honesty through the lies are just good clean fun. When the manager of Carling was asked if they couldn’t make a profit at $1.75 a case, he replied “well, you can’t make a large profit.”

This in interesting… well, to me at least. It is from the

This in interesting… well, to me at least. It is from the