Ah, the 1500s. Remember them? They were great. Jeff’s comments yesterday got me thinking about causes for changes like the introduction of coke in the early 1600s and its application in malting at mid-century. See, there is this idea that goes well beyond brewing history that somehow folk in the past were dim and ate poorly that casts a shadow on the idea that coke was introduced to make pale malt and while Jeff didn’t speak to that, the temptation to reverse the clock and make chronology run backwards can be seen at play. I don’t believe any of it. For the most part, folk didn’t sit around glum at the state of their technology wishing for a better tomorrow. They were pretty much as clever as we are just that they operated within a construct of technology and knowledge that differed from us. No? Well, just don’t be thinking what the future will make of us, then.

Ah, the 1500s. Remember them? They were great. Jeff’s comments yesterday got me thinking about causes for changes like the introduction of coke in the early 1600s and its application in malting at mid-century. See, there is this idea that goes well beyond brewing history that somehow folk in the past were dim and ate poorly that casts a shadow on the idea that coke was introduced to make pale malt and while Jeff didn’t speak to that, the temptation to reverse the clock and make chronology run backwards can be seen at play. I don’t believe any of it. For the most part, folk didn’t sit around glum at the state of their technology wishing for a better tomorrow. They were pretty much as clever as we are just that they operated within a construct of technology and knowledge that differed from us. No? Well, just don’t be thinking what the future will make of us, then.

What was the English speaking beery world like over four centuries ago? In his “Dietary” of 1542, Andrew Boorde made himself clear about what he considered was the best ale:

“Ale is made of malte and water; and they the which do put any other thynge to ale than is rehersed, except yest, barm, or goddesgood doth sophysicat there ale. Ale for an Englysshe man is a naturall drinke. Ale muste have these properties, it muste be fresshe and cleare, it must not be ropy, nor smoky, nor it must have no wefte nor tayle. Ale shulde not be dronke under .V. dayes olde. Barly malte maketh better ale than Oten malte or any other corne doth…

Not smoky. Interesting. In the latter 1500s we are still in the world of beer and ale with beer being very much the newcomer on the block. In the 1550s, beer is a manly burly drink while ale is for the ladies and young. By 1577, it is described as being for the old and ill.¹ Malt markets were part of the weekly cycle of life. In York:

…the 16th century the malt market was held on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, near St. Martin’s Church in Coney Street; the hours of sale to citizens and foreigners were regulated and a bell rung to announce its opening. It was permissible for malt to be brought into the city on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays if it had already been sold.

Note that it is a market for sales to citizens by maltsters coming into that city. In Elizabethan England was less than five million and Stratford upon Avon had just about about 1,500 inhabitants. A report in the town’s records by Shakespeare’s local pal still living there, Richard Quyney, gives a contemporary picture of the important role of malt: “Auncient in thys trade of malteinge & have [sic] ever served to Burmingham from whence, Walles, Sallopp, Stafforde, Chess. & Lanke allso are served.” Stratford is a regional malt hub with an extended reach. Quyney also noted a downside of this community asset:

….houses made to noe other use then maltinge’ and complains that the town is “deceived by reson of contreye malte kylnes wch make ther owne Benifytt in malting ther Barley att home, wch usuallie was Brought to be solde att or m’kett & ther made & converted to malte.” A survey taken in 1598, a year of high prices and great distress, shows that 75 persons, probably a third of the more substantial householders in the borough, had stores of malt on their premises, amounting in all to 696 quarters, while 30 of them had also 65 quarters of grain of various kinds…. Of the malt returned in the survey of 1598 rather less than two-thirds is classed as townsmen’s malt; the remainder, 250 quarters, is strangers’ malt.

The “strangers” storing their malt included many leading citizens from the neighbouring region. In a time of famine, this stockpiling in Stratford was not welcome and a resident of Stratford invited the Earl of Essex, a favorite of the Queen, to come to the town and restore commercial order by having the maltsters hanged “on gibbetts att their owne dores.”² Sounds like speculation going on. Why? In that same decade, use of malt for home use is being restricted due to a lucrative market export market for English beer having been established.³ There is now a developing opportunity for making money in brewing and malting at a scale.

In addition to pressure from investors and speculators, there was something of a crisis in malt and fuel supplies as far back as the mid-1500s:

…the forests around York had greatly diminished and receded. Chiefly for this reason the malt kilns were in 1549 closed for two years and a survey of disforestation for eight miles around was instituted. At this time, too, the commons included the dearness of fuel in their bill of grievances and the M.P.s were asked to seek a commission from the king to check disforestation.

The crisis of English deforestation led to a search for fuel alternatives and the main alternative was coal. The timber crisis was most acute in England from about 1570 to 1630 during which making coke from coal was invented. The vast majority¹¹ of coal, however, was not appropriate for malting. Unlike the best malt from wood kilns, coal would be worse than smoky, it would be fouled. Which, when you have a population needing beer as well as new speculating investors wanting beer to export is not good.

So where does that get us? To a world around 1600 where traditional pale malt making continues using diminishing resources including wood but also wheat-straw, rye-straw, barley-straw or oaten-straw… and, if it is all you have, dried ferns. In 1642, an entire contemporarylifetime later, coke – only conceived of as a product derived from coal in 1603 – is first used to make pale malt without the traditional bio-mass. Was it actually due to the need to “invent” smoke-free pale ale? Not really. But greater volumes of pale ale would have become available. Was it due to the opportunity to invest in brewing to maximize the export opportunity as part of a larger reordering of society and resources? Probably. Tensions from the middling gentry, the rise of non-conformity, English colonization of America and trade with other parts of the world took all off at this same time, creating the world we live in today. But, really, the shift to malting with coke occurred because there was no choice. The forests and other sources of bio-mass were disappearing fast.

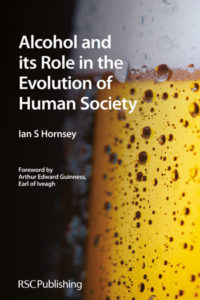

¹See A History of Beer and Brewing by Ian S. Hornsy, (RSC, 2003) at page 353.

² See Shakespeare’s Professional Career by Peter Thomson, page 10.

³ See Honsey at page 351. Also there were objections to the number of malt-kilns in York according to “The Tudor economy and pauperism“, footnote 31 at British History Online: “Richard Layton told Cromwell in 1540 that the demand for malt played into the hands of corn regraters and also caused every idle knave in York to get an alehouse, so impairing honest trade.” A regrater was a middleman, a retailer, a taker of a slice.

¹¹In the late 1880s, a grade of Welsh coal was called “best malting coal” due to it having less than 1% sulphur, 0% arsenic and very low ash. One business listing from 1881 from a Swansea merchant claims: Carvill Bros. (& importers), 34 Merchants quay, Drysdale G.A. (best malting coal as supplied to many of the largest maltsters, brewers and distillers in the kingdom. Prices quoted delivered in truck loads to any railway station in England, also f. o. b. at Swansea, or delivered to any port, including cost, freight, and insurance ; exporter of best lime burning & hop drying anthracite coal) Address, Mailing Coal Offices, Swansea.

That is Alcohol and its Role in the Evolution of Human Society by Ian S. Hornsey. I had no idea. In a work of beer writing that is still trying to find its way, seeking to evolve from fanboy gushing or trade focused boosterism or underdeveloped efforts at business journalism, Hornsey’s 2004 book

That is Alcohol and its Role in the Evolution of Human Society by Ian S. Hornsey. I had no idea. In a work of beer writing that is still trying to find its way, seeking to evolve from fanboy gushing or trade focused boosterism or underdeveloped efforts at business journalism, Hornsey’s 2004 book

This is another book from Brewers Publications that bridges the worlds of brewers and drinkers. As with Stan’s excellent

This is another book from Brewers Publications that bridges the worlds of brewers and drinkers. As with Stan’s excellent