One of the odder things about the history of American brewing is the failure to get a handle on the extent to which pre-lager brewing existed before roughly 1840. Earlier this fourth of July, Jeff, who is pretty good with this stuff, described it in negative terms this way:

For centuries, it was an immigrant’s drink… Locals pretty much didn’t touch the stuff. In 1763, New England alone had 159 commercial distilleries, yet were only 132 breweries in the entire country in 1810. By 1830, the US had 14,000 distilleries, towns tolled a bell at 11 am and 4 pm marking “grog time,” and the per capita rate of consumption was nearly two bottles of liquor a week for every drinking-age adult. We only started drinking beer when another wave of immigrants, the Germans, brought it in the 1840s. Their lagered beer, in a time when no one understood the mechanism of yeast, was clean, tasty, and popular. We enjoyed a flowering of brewing in the following decades–German beer, brewed by immigrants. It was stubbed out by the great puritan experiment of Prohibition, which also says a lot about America.

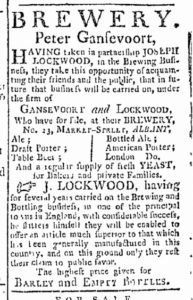

Setting aside the question of who was a “local” in the pre-Revolutionary context – are we talking about Mohawks? – by any account, it is pretty clear that there was plenty of ales, beers and porters going around the US before the Revolution and even before that later lager revolution. Craig has mapped at least 18 identifiable pre-lager breweries in Albany, NY – one of the larger national brewing centres with a history there of beer that predates 1776 by about 150 years. Gregg Smith wrote an entire book entitled Beer in America: the Early Years – 1587-1840 which does not seem to get the attention it deserves. Heck, Ben Franklin himself welcomed Washington himself to Philadelphia in 1787 with a cask of dark beer.

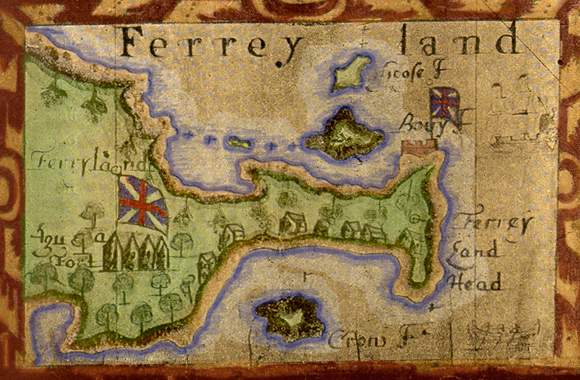

As a Canadian, I am not sure why there is this national amnesia with our cousins to the south. Yes, there were certainly other drinks. I recommend highly the chapter on apples in Michael Pollen’s book The Botany of Desire which explains how apples were an important pioneer resource for milder cider, hard applejack as well as the sterilizing properties of alcohol. There was also a strong tradition especially at the frontier wherever it was found for home made fermentables and distilled booze. The Whiskey Rebellion of the 1790s in western Pennsylvania is called that for a good reason. But there also seems, despite the available record of ale production, a need to link light lager introduced to America in the 1830s and ’40s as being somehow something of a more American brewing genesis – even though pale light lager was at the time an unwelcome immigrants’ beverage that led to its own share of troubles. We also forget how few Americans there were in the colonial and Revolutionary times and how little of the present US they had actually settled. Beer is always part and product of a larger and a peaceful sort of economy.

American beer history is 200 years older that some would say – and far more complexly interesting, too. Last night I got to annotate a brewer’s log for an 1833 pale ale that, with a little more research, could likely be drilled down to where the field where the malt was grown. With any luck, it will be made for sampling this fall. By a Canadian brewer with pre-Revolutionary connections I won’t get into now. With a bit more luck, more of these brewing account books and day logs will be found and the actual pre-lager history of the US can be described.