This year’s vintage base ball game was remarkable. The weather was so hot I thought that I was going to faint when I slowed into second on a couple of doubles. The team had a few new faces but was as keen as ever and took both games after never winning a single game in the USA in the four previous seasons. Well, there was 2008 when the game was rained out. We declared that we had not lost by default.

Category: History

All That Base Ball Was Really About That Pitcher

I indulged in my other odd hobby yesterday. 1860s – 70s base ball. Two words. No gloves. No sliding. The ball springs off the bat with about as much zip as an Edam cheese would. Underhand pitching and bats that are like swinging a 2 x 4 fresh from the lumber yard. I put the thing together with friends. We took on graduating cadets from our Royal Military College as well as a mixed team of upstate New Yorkers from Canton and Rochester NY. The final was a 3-2 victory for the Americans. The team that became the Atlanta Braves beat Kingston on the same field 138 years ago… by a slightly larger margin.

And after it all, we retired to the brew pub. There is only one in the City so that’s what we call it. Over twenty folk wanting to relax over a few beer and get to know each other. Lively talk about the sad state of regional teams like the Bills and the Leafs, discussions about the different gun law ending with the trump card of a cadet explaining the fire power he’s been trained to use. And the beer. I hadn’t realized that oatmeal stout was not available in pitchers so I had a pint and bought a pitcher to share of the pale ale, both brewed by Montreal’s McAuslan Brewing. I couldn’t remember the last time I had a pitcher. Sounds sad, doesn’t it but life with the many rug rats does have its realities. What did I like about having one? The conviviality. The vessel was meant for sharing. Slopping pours topped up this glass and that. As talk ebbed and flowed from the Bills to bazookas.

Easlakian Vintage Base Ball Madness Strikes!

So, How Was That Beer George Made Anyway?

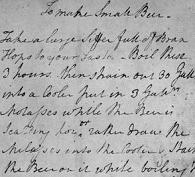

Some buzz around the beer news that the Coney Island / Shmaltz Brewing Company is brewing up a recipe of George Washington’s beer for a charity gig… and a cheater version with roasted malts for those who might want to pretend. Here is the recipe entitled “To Make Small Beer” as set out by the Gothamist:

Some buzz around the beer news that the Coney Island / Shmaltz Brewing Company is brewing up a recipe of George Washington’s beer for a charity gig… and a cheater version with roasted malts for those who might want to pretend. Here is the recipe entitled “To Make Small Beer” as set out by the Gothamist:

Take a large Siffer [Sifter] full of Bran Hops to your Taste. Boil these 3 hours then strain out 30 Gall[ons] into a cooler put in 3 Gall[ons] Molasses while the Beer is Scalding hot or rather draw the Melasses (sic) into the cooler & St[r]ain the Beer on it while boiling Hot. let this stand till it is little more than Blood warm then put in a quart of Yea[s]t if the Weather is very Cold cover it over with a Blank[et] & let it Work in the Cooler 24 hours then put it into the Cask—leave the bung open till it is almost don[e] Working—Bottle it that day Week it was Brewed.

The recipe is in the New York Public Library‘s collection and dates from 1757 – when George was still a Loyalist and a couple of years before Jeffery Amherst’s spruce beer from a couple of colonies to the north. Interestingly, each uses 3 gallons of molasses to thirty gallons of brew. The real difference is that George says hop to taste while Jeff boils seven pounds of spruce until the bark comes off. Neither look all that appealing. And I am not sure what George meant by the “Bran Hops.” Is the sentence supposed to be “Take a large Siffer [Sifter] full of Bran Hops to your Taste” or is there a missing punctuation mark so that it would read “full of Bran – Hops to taste”? Or were “bran hops” something that meant something to someone somewhere?

This report suggested that the Washington beer would work out at 11%… hardly small beer. And Amherst states that his beer can be bottled to keep “a great while.” I dunno. Were these desperate beers for desperate times? In a way, maybe they were the predecessors of commodity beer – a means to an end.

America’s Communalist Christian Foundation

I have been reading a lot this winter. Lots and lots of histories – mainly US but plenty about the founding of Upper Canada, too, though those texts are fewer and far between. Right now, I am reading John Winthrop: America’s Forgotten Founding Father by Francis J. Bremer, a book about the first Governor of the Massachusetts Bay colony founded in 1630 a decade after the Pilgrims hit Plymouth Rock. It is a great ride, covering his grandfather’s birth in 1480 to his own death in 1648 and contextualizes his life in the ebb and flow of the state’s regulation of religious practices from pre-Luther to the lead up to the English Civil War, also the name of an excellent song by The Clash. But this is the key bit. The middle bit to his sermon to his fellow passengers on the event of their departure to New England from the Old World:

… for wee must Consider that wee shall be as a Citty upon a Hill, the eies of all people are uppon us; soe that if wee shall deale falsely with our god in this worke wee have undertaken and soe cause him to withdrawe his present help from us, wee shall be made a story and a byword through the world, wee shall open the mouthes of enemies to speake evill of the wayes of god and all professours for Gods sake; wee shall shame the faces of many of gods worthy servants, and cause theire prayers to be turned into Cursses upon us till wee be consumed out of the good land whether wee are going…

See that? The new order of New England shall not only be a candle on a stand rather than under a bushel (basket) – but if they were to screw up “wee shall shame the faces of many of gods worthy servants.” That is a heavy burden but one that acts as a prophesy, reaching to today from 381 years ago. What was the way to avoid having “prayers to be turned into Cursses upon us”? Worship of those other gods, pleasures and profits. And also failing to make “others Condicions our owne rejoyce together, mourne together, labour, and suffer together, allwayes haveing before our eyes our Commission and Community in the worke.” Pinkos! I see Pinkos! Pinkos like me!

Next time you hear about how American was founded on faith, you may want to agree in part and note that what sort of Christian by which it was founded.

Mmm… What I Need Is A Big Bowl Of Thick Beer!

I knew this. I think I knew this anyway:

I knew this. I think I knew this anyway:

“This process is much like how you would do in a fourth-grade germination science project, where the grains would be soaked in water for about 24 hours, drained and then laid between sheets of cloth until they sprouted,” said Amanda Mummert, an anthropology graduate student helping Armelagos with his research. After germination, the grains were dried and then milled into a flour used to make bread. Streptomyces bacteria most likely entered the beer-making process either during the storage or drying of the grain or when the bread dough was left to rise. Nubian brewers would take the dough and bake it until it developed a tough crust, but retained an almost raw center. The bread was broken into a vat containing tea made from the unmilled grains. The mixture was then fermented, turning it into beer. The final product didn’t look much like the pint of amber you sip at your local watering hole. “When we talk about this ancient Egyptian beer, we’re not talking about Pabst Blue Ribbon,” Armelagos said. “What we’re talking about is a kind of cereal gruel.”

I knew that. Not that bacteria stuff. No, not that. Forget all that medical properties stuff. Look at that word “gruel”! I think there was reference to the thickness of 1500s gruel beer back in Martyn’s Beer: The Story of The Pint which I am surprised to now read that I blogged about seven and a half years ago. There is stuff in Hornsey about beer as gruel as well. Boozy porridge. So, how is it when we are presented with these supposedly authentic ancient beers, well, they pours like water or least an IPA?

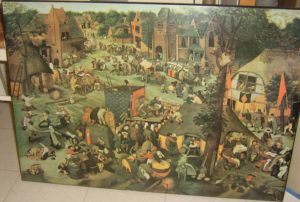

More to the point, don’t you want to try some breakfast gruel beer? Couldn’t we make it like it was enjoyed back then? Not the contemporary southern African version for 12 to 20 but the big vat whole dang community serving sized pot o’ Quaker Oats meets Budweiser. If we look again at “Village Kermis With Theater and Procession” by Pieter Bruegel the Younger (discussed in in 2007 in terms of the pub game in the lower left) we see in the lower center the making of a big mess of something being sucked back by the crowd, right across the street from the joint I’d guess was the tavern. Have a look at the painting Bruegel maybe ripped off and the detail is even better. I am not suggesting we need to get all deep about this stuff but does anyone do a village kermis with gruel booze anymore – other than, say, in rural Romanian where I am pretty sure I will never find myself? Would people folk to such a legitimate recreation as much as for another thinly veiled faux stab at brand buffing? Apparently the children’s games scholars are already at it.

Breaking News: Their First Beer Festival In 400 Years

Big news out of Lyme Regis in Dorset, England as they are reviving or at least reinterpreting a festival that ended back in 1610.

The ale will be in full flow at Lyme Regis when the town hosts its first beer festival in 400 years. A festival called The Cobb Ale started in Lyme in the 14th century and lasted for around 250 years. The annual knees-up was held to raise money for the maintenance of the Cobb but it was stopped around 1610 by the Puritans. Now three local brewers, the Mighty Hop Brewery and Town Mill Brewery, both in Lyme Regis, and North Chideock’s Art Brew, will revive the tradition for a one-day festival in March.

Friggin’ Puritans. They ruin all the fun. But there is fun – real fun – to be had and it is not some phony baloney made up thing. You know that’s true because the Victorians wrote about it. That clip way up above is from the 1856 books called The Social History of The People of the Southern Counties by George Roberts who spends twenty pages or so – from 327 to 346 or so – on the history of the Cobb Ale festival. It is great stuff.

OK, it may be an utter lie as might be the renewal but it is very entertaining. Martyn and other cleverer folk than me know more about this stuff but the very idea that something celebrating 1376 could be celebrated still is very appealing to me. I might take it so far that, for me, the distinction between “ale” as festival and “ale” as the juice that makes the community festive described by both Martyn and George above escapes me a bit in the light of the knowledge that they who celebrated knew the resonance of one meaning to the other. It’s a bit like “party” as both noun and verb in the sense that one parties at the party. Having an ale at an ale must have been all quite affirming.

Ontario: Fryfogel’s Tavern, Near New Hamburg, Perth Co.

Ever since I opened my copy of Julia Robert’s In Mixed Company, a history of the taverns of Upper Canada from the 1780s to the 1850s, I have wondered how many of our Upper Canadian pioneer taverns there might be left out there. Well, I passed one today – the Fryfogel Tavern – and thought I would get out of the car and have a look around.

Fryfogel’s Tavern, more graciously called an inn on the official road side sign, has sat by the road between Kitchener and Goderich for 166 years, though it has not apparently acted as a tavern for most of that time. You will recall from last summer’s posts on Ontario’s history that the land to the west of Lake Ontario starts opening up and breweries start opening up in the 1820s and 30s. The Canada Company’s plan of settlement of the area is discussed here and the way of life at the time of 1830s settlement of the district can be found in this letter from an original settler, John Stewart. Each source mentions Mr Fryfogle or Fryfogel when his tavern was a log cabin. Roberts indicates that the later 1840s form of the tavern is in the Georgian style and that this was the template for taverns for much of the pre-Confederation period:

The Georgian style worked well to project an image of prosperity and comfort, particularly in the practical sense that it enabled different activities to go on in the house at the same time.

Owned by the county’s historical foundation, it well kept but something of a shame that it is not in use though that seems to be in the plans. Next to it to the west sits the site of the 1828 cabin that preceded it as the home of the family. To the east runs Tavern Brook. The original owners are buried across the road.

Delaware: Theobroma, Dogfish Head, Milton

Mark Dredge has a piece in this morning’s Guardian out of the UK entitled “The Beer of Yesteryear” which scans the range of recent brewing efforts to recreate beers older than, say, 500 years ago. These are beers which use ingredients available to former culture including Theorbrama by Dogfish Head. I had one on hand and thought I would see if it has any appeal. Mark tells me:

Mark Dredge has a piece in this morning’s Guardian out of the UK entitled “The Beer of Yesteryear” which scans the range of recent brewing efforts to recreate beers older than, say, 500 years ago. These are beers which use ingredients available to former culture including Theorbrama by Dogfish Head. I had one on hand and thought I would see if it has any appeal. Mark tells me:

Theobroma, part of Dogfish’s Ancient Ale series, is based on “chemical analysis of pottery fragments found in Honduras which revealed the earliest known alcoholic chocolate drink used by early civilizations to toast special occasions.” It contains Aztec cocoa powder and cocoa nibs, honey, chillies and annatto.

The bottle adds that it is based on chemical residual evidence from before 1100 BC with additives from later Mayan and Aztec drinks. So, seeing as the Aztecs come from about 1300 to 1600 AD, it is sort of a made up mish mash. Its as much a traditional drink as one from, say, that one Eurotrash era that stretched from the Dark Ages of around 800 AD to the world of George Jetson in the year 2537 AD. That would be an excellent era… right?

Well, as a beer it is a bit of a disappointment as well. Booze overwhelms pale malt which is undercut by the exotic herbs all of which has an oddly “beechwood aged” tone to it. I get the cocoa. I get the honey. But I don’t care all that much. It leaves me disappointed like that imperial pilsner experiment of Dogfish Head’s in 2006. Only moderate respect from the BAers. A bit of a boring beer that may be the result of a fantastically interesting bit of archeological work. Who knows? Maybe the sense of taste of those Central American practitioners of human sacrifice wasn’t as haute as one might have expected. Or maybe it paired well.

What Is My Methodology? Perchance Schmethodology?

I have found myself wondering what the heck I am doing with all this Albany Ale stuff but I’m not too concerned. It is interesting in itself and I think it is informing me on a pretty interesting big picture question – what makes the Albany and the Hudson River so different from the St. Lawrence Valley, my river. You will recall that during Ontario Craft Beer week this past June, I wrote a number of posts on the development of Ontario after the American Revolution but it is important to remember that, like the Dutch in the Hudson, the upper St. Lawrence also had a 1600s existence when it was all New France.

The big question I have is why did Albany create this export trade while my city did not? There are some basic answers around the odd semi-autonomous existence of early Albany while Kingston has been firmly tied to its Empires. Also, there is simple geography with Albany being a deep water seaport while Kingston has always sat behind rapids and locks. Difference makes sense. But is that it? Looking more closely, there are the details. And details can get obsessive with a range of ways to get at them:

- Who is doing what? You can find this information in newspaper ads, business directories and gazetteers. People have always been obsessed with what others are doing and putting it in a central place so thoers can see it. Google is making this information available to all for free without travel.

- How is it being taxed? Beer has attracted excise and sales taxes for centuries. This is Professor Unger’s approach. I have not really gotten into this level – yet.

- What is being brewed? Ron Pattinson’s obsession with day to day brewing logs is a less to us all in detail. And he is getting some of the brewing replicated as his trip to Boston this weekend shows.

- Who is allowed to deal with beer? Beer is also regulated along with all booze. Tavern and brewery license records exist as do the court records of applications and charges for violations. Taverns and Drinking in Early America by Salinger is largely built on this sort of analysis.

- Where does the beer go? Pete Brown has taught us a lot about that. Mapping trade routes is another avenue to this stuff. I have asked about Dutch East India ale as well as Bristol’s Taunton ale. What made for the demand for these beers and what made them eoungh good value to the other end of the world to buy them?

- Beyond all this, there is Martyn. The funny thing about Martyn’s work for me is that I can’t understand where he gets his data – his focus on words amazes me. I don’t know if I could be so elemental and authoritative. But West Country White Ale inspires.

So, there is a lot there – a lot for anyone in any town to use to figure out the path of their local brewing trade. And there are a lot of other people hunting as well. Me, I have no idea what I will learn about Albany or Kingston or beer or anything else. But it is worth the hunt. And why not? Weren’t we all supposed to be citizen journalists, historians and novelists? Isn’t that the promise of the internet or is it really more like that personal jet pack we were all supposed to have by now? I think you might all want to get all be scratching around a bit – even if not as obsessively as others.