Anyone interested in beer in Canada – or even colonial North America – really ought to have this book on the shelf. 2009’s In Mixed Company: Taverns and Public Life in Upper Canada is a series of essays on topics related to the structure, regulation and use of taverns in what later became Ontario but what was called Upper Canada during the era in question. Covering roughly 1790 to 1860, Roberts describes a certain sort of drinking and socializing experience, showing where the lines of class, race and gender existed and also showing how some of those lines were far fuzzier than we might presume.

Anyone interested in beer in Canada – or even colonial North America – really ought to have this book on the shelf. 2009’s In Mixed Company: Taverns and Public Life in Upper Canada is a series of essays on topics related to the structure, regulation and use of taverns in what later became Ontario but what was called Upper Canada during the era in question. Covering roughly 1790 to 1860, Roberts describes a certain sort of drinking and socializing experience, showing where the lines of class, race and gender existed and also showing how some of those lines were far fuzzier than we might presume.

Be warned: this is an academic text. There are 169 pages of essay and 48 pages of endnotes and bibliography. But like Hornsey or, say, Xhosa Beer Drinking Rituals, it would really do you all a bit of good to get some proper reading in. You’d learn things like the first wave of taverns built after the creation of the colony in 1791 were owned by the government, run by tenants as part of the necessary roads and communications infrastructure. Until the development of more exclusive principle taverns and then hotels in the larger centres, taverns provided space where different backgrounds met and interacted, where people in transit or transistion lived, where business and political debate was conducted. You’ll see how Upper Canadians saw themselves as different from what they called Yankees and, as the late Georgian became the early Victorian, how they developed internal divisions to distinguish themselves one from another

I have been fumbling around unsuccessfully for a reference from Nova Scotia confirming the meaning of “tavern” as a late 18th century offering wine, tea and other proper fare – a great change from my late 1900s use as a beer hall. As the author points out, during this era and in this place, the tavern was a licensed facility, regulated by law, providing civic purpose. It was subject to social and legal rules but offered a location for every thing from the holding of court to the holding of cockfighting. And, while there is no real focus on the drinks consumed, there is interesting information including how hard spirits appear to be quite popular including punches and what we would now see as simple cocktails, including gin slings.

Robert’s style is precise and dense but quite enjoyable – especially given the fairly brief length of the interrelated essays forming the seven chapters of the book. Her observations and conclusions are interesting and well supported both in terms of argument and endnote. The most interesting portions for me were the chapters focusing on diaries, one kept by a tavern keeper in what was then York around 1801 and another on excerpts from one kept a regular tavern goer in my city of Kingston in the early 1840s. The comparison of the earlier period when the colony had a population of 34,600 and 108 licensed taverns to the 1840s when there were over 400,000 more Upper Canadians and 1,446 taverns provides illustration of the growing complexity as well as development of peace in a colony that was born of and suffered threat of war from the south regularly until the mid-century.

This era covered in this book is largely just after the era I wrote about in my Ontario Craft week posts on Kingston and its roots in New York state. It is an important era given that it is when this newly formed part of than British North America distinguishes itself in its controlled settlement patterns from the rougher experience in the United States. By placing us in that era, illustrating its social and civic centres, Roberts provides us with a useful context for understanding even at this distance of years.

Anyone interested in beer in Canada – or even colonial North America – really ought to have this book on the shelf. 2009’s

Anyone interested in beer in Canada – or even colonial North America – really ought to have this book on the shelf. 2009’s

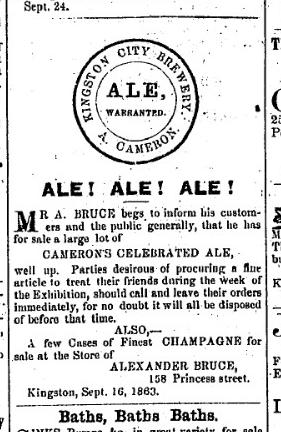

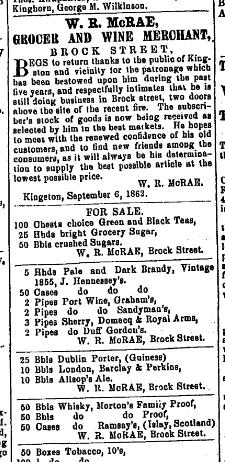

Kingstonians were not only enjoying local brewed beers, however celebrated, in the early 1860s as the ad to the left from the same paper’s

Kingstonians were not only enjoying local brewed beers, however celebrated, in the early 1860s as the ad to the left from the same paper’s