I have been thinking more about this pre-1850 invention called “Albany ale” and I am a bit surprised to find so many references to it of one sort and so few references of another. The stuff was made in volume, transported and traded over great distances but now seemingly forgotten to memory. As we will see [Ed.: building suspense!] when we discuss the quote above, it was the stuff of memory even at the end of the 1800s.

But what was it? As noted this morning by Robert in the comments, there is a brief description of Albany’s production of ale in the 1854 book The Progress of the United States of America by Richard Swainson Fisher at page 807:

The business of malting and brewing is carried on to a great extent In Albany; more than twenty of such establishments are now in operation, and Albany ale is found in every city of the Union, and not unfrequently in the cities of South America and the West Indies. The annual product is upward of 100,000 barrels of beer and ale.

Similar text was published in the Merchant’s Magazine in 1849 except it was 80,000 barrels. Interesting to see how far it traveled – California, West Indies and South American in addition to references to Newfoundland in yesterday’s post. There is also this passage in 1868’s A history of American manufactures from 1608 to 1860 Volume 1 by John Leander Bishop and a few others:

…Kuliu mentions, in his account of the Province in 1747, that he noticed large fields of barley near New York City, but that in the vicinity of Albany they did not think it a profitable crop, and were accustomed to make malt of wheat. One of the most prosperous brewers of Albany during the last century was Harman Gansevoort, who died in 1801, having acquired a large fortune in the business. His Brewery stood at the corner of Maiden Lane and Dean street, and was demolished in 1807. He found large profits in the manufacture of Beer, and as late as 1833, when the dome of Stanwix Hall was raised, the aged Dutchmen of the city compared it to the capacious brew kettle of old Harme Gansevoort, whose fume was fresh in their memories.’ [Note: Munsell’s Annals of Albany. Pleasentries at the expense of Albany Ale and its Brewers are not a recent thing. It was related by the old people sixty years ago of this wealthy Brewer, that when he wished to give a special flavor to a good brewing he would wash his old leathern breeches in it.]

Was Albany ale originally a wheat ale? It was obviously big stuff in the state’s capital for decades.

Reference to Albany ale also appears in an illustration of a principle in a book of proper English usage. In the 1886 edition of Every-day English: A Sequel to “Words and their Uses” by Richard Grant White where we read the following at page 490:

I cannot but regard a certain use of the plural, as “ales, wines, teas,” “woolens, silks, cottons,” as a sort of traders’ cant, and to many persons it is very offensive. What reason is there for a man who deals in malt liquor announcing that he has a fine stock of ales on hand, when what he has is a stock of ale of various kinds ? What he means is that he has Bass’s ale, and Burton ale, and Albany ale, and others; but these are only different kinds of one thing.

The fifth 1886 edition of Words and their Uses by the same Mr. White contains no reference to Albany ale but does indicate he was a prolific US author who lived from 1821-1885. Does the later use by White imply it was an easily understood example? Probably.

In the New York journal The Medical Record of 1 March 1869, there is an article entitled “Malt Liquors and Their Theraputic Action” by Bradford S. Thompson, MD the table to the right is shown that clearly describes Albany ale as a sort of beer the equal to the readers understanding as London Porter or Lager-Bier. I am not sure what the table means from a medical point of view but it clearly suggest familiarity… at least amongst the medical set.

In the New York journal The Medical Record of 1 March 1869, there is an article entitled “Malt Liquors and Their Theraputic Action” by Bradford S. Thompson, MD the table to the right is shown that clearly describes Albany ale as a sort of beer the equal to the readers understanding as London Porter or Lager-Bier. I am not sure what the table means from a medical point of view but it clearly suggest familiarity… at least amongst the medical set.

In 1875, it is described in a travel book called Our Next-door Neighbor: A Winter in Mexico by Gilbert Haven (who seems to not have been a lover of the drink himself) at page 81:

Here, too, we get not only our last look at Orizaba, but our first at a filthy habit of man. Old folks and children thrust into your noses, and would fain into your mouths, the villainous drink of the country – pulqui. It is the people’s chief beverage. It tastes like sour and bad-smelling buttermilk, is white like that, but thin. They crowd around the cars with it, selling a pint measure for three cents. I tasted it, and was satisfied. It is only not so villainous a drink as lager, and London porter, and Bavarian beer, and French vinegar-wine, and Albany ale. It is hard to tell which of these is “stinkingest of the stinking kind.” How abominable are the tastes which an appetite for strong drink creates! The nastiest things human beings take into their mouths are their favorite intoxicants.

So, along with grammarians and the drinking medical set, Albany ale was also a name known to the non-drinking traveling set in the post-Civil War United States. It was, as a result, something we might consider “popular” in its day.

Oddly, the story of Albany ale does not seem to make it deep into the 1900s. Without making an exhaustive study, I don’t see reference to “Albany ale” in Beer and brewing in America: an economic study” by Warren Milton Persons from 1940. It is not indexed in Beer in America: the early years, 1587-1840 by Gregg Smith. It does not seem to be in Ambitious Brew: The Story of American Beer by Maureen Ogle as it really starts with the the rise of lager is in the second half of the 1800s. Why did it fall so far so fast?

That quote way up there? The one at the top? It’s from an 1899 New York Times article entitled “Kicked 90 Years Ago Just the same as Now” in which a 96 year old New Yorker still employed as a municipal engineer who was interviewed about the City’s old days. Talking about his youth in the 1830s, he said “Albany ale was the beverage then that lager beer is today, and a mighty good drink it was.” So, lager likely killed it off but only after it had its day and was enjoyed widely in the days before rail transportation both within the United States and abroad.

2015 Update: came across book by Mr Haswell, the 96 year old New Yorker mentioned up there.

Where was I? The 1830s and 40s? About there. Local breweries popping up as settlers move west, filling up southern Ontario right up to the Lake Huron coast. Familar names start popping up. In 1835, James Morton is operating out of the old Molson brewery on the Kingston waterfront. John Sleeman starts up in 1836. In 1843, Thomas Carling builds a brewery in London, Ontario. And in 1847 John Labatt enters into a partnership with an existing brewer also in London and Quebec brewers Molson have another go, this time further west along the Lake Ontario shore at Port Hope. It lasts until 1868. Facts stolen from Sneath.

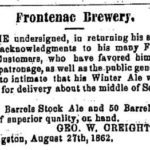

Where was I? The 1830s and 40s? About there. Local breweries popping up as settlers move west, filling up southern Ontario right up to the Lake Huron coast. Familar names start popping up. In 1835, James Morton is operating out of the old Molson brewery on the Kingston waterfront. John Sleeman starts up in 1836. In 1843, Thomas Carling builds a brewery in London, Ontario. And in 1847 John Labatt enters into a partnership with an existing brewer also in London and Quebec brewers Molson have another go, this time further west along the Lake Ontario shore at Port Hope. It lasts until 1868. Facts stolen from Sneath. They had to make products that both reflected and appealed to their clients and the environment. The had to go with a shot of whisky – whether it was made with barley or rye. In 1862 here in Kingston, Mr. Creighton of the Frontenac Brewery was selling stock ale and porter with the promise of a winter beer in the fall. Farther to the west in 1872, Labatt is selling only pale ale and stout in its local paper.

They had to make products that both reflected and appealed to their clients and the environment. The had to go with a shot of whisky – whether it was made with barley or rye. In 1862 here in Kingston, Mr. Creighton of the Frontenac Brewery was selling stock ale and porter with the promise of a winter beer in the fall. Farther to the west in 1872, Labatt is selling only pale ale and stout in its local paper.