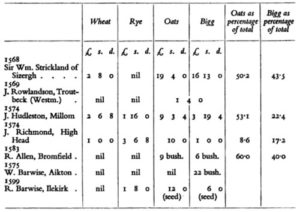

That image up there has little to do directly with this post. It’s from a book entitled A Short Economic and Social History of the Lake Counties, 1500-1830 by C.Murray, L.Bouch and G.Peredur. It popped into my Google search results as an answer to the query “William Strickland barley.” I was looking for William Strickland, 6th Baron Boynton, esq. (February 18, 1753 – January 8, 1834), the 18th-century gentleman farmer and writer from Yorkshire, England who was the eldest son of Sir George Strickland of York, England, from the ancient English Strickland family of Sizergh and who wrote A Journal of a Tour of the United States of America, 1794–95. You will note, however, that both are Stricklands of Sizergh. According to Burke’s the William of 1568 was an MP and may have even sailed with Cabot to the New World. The William I am looking for was the son of George, son of William, son of William, son of Thomas, son of the 1st Baron William, son of Walter, son of the William who may have sailed with Cabot. My William is the great great great great great grandson of the one who in 1568 grew a crop which included 43.5% bigg.

That image up there has little to do directly with this post. It’s from a book entitled A Short Economic and Social History of the Lake Counties, 1500-1830 by C.Murray, L.Bouch and G.Peredur. It popped into my Google search results as an answer to the query “William Strickland barley.” I was looking for William Strickland, 6th Baron Boynton, esq. (February 18, 1753 – January 8, 1834), the 18th-century gentleman farmer and writer from Yorkshire, England who was the eldest son of Sir George Strickland of York, England, from the ancient English Strickland family of Sizergh and who wrote A Journal of a Tour of the United States of America, 1794–95. You will note, however, that both are Stricklands of Sizergh. According to Burke’s the William of 1568 was an MP and may have even sailed with Cabot to the New World. The William I am looking for was the son of George, son of William, son of William, son of Thomas, son of the 1st Baron William, son of Walter, son of the William who may have sailed with Cabot. My William is the great great great great great grandson of the one who in 1568 grew a crop which included 43.5% bigg.

I find this interesting because on 15 July 1797 George Washington wrote a letter to William Strickland which opens with “Sir, I have been honored with Yours of the 30th of May and 5th of Septr of last Year” and containing the following:

Spring Barley (such as we grow in this Country) has thriven no better with me than Vetches. The result of an Experiment made with a little of the True sort might be interesting… You make a distinction and no doubt a just one between what in England is call’d Barley, and Big or Beer, if there be none of the true Barley in this Country—it is not for us without Experience to pronounce upon the Growth of it; and therefore, as noticed in a former part of this letter it might be interesting to ascertain whether our climate and soil would produce it to advantage. No doubt as your observations while you were in the United States appear to have been extensive and accurate it did not escape You, that both Winter and Spring Barley are cultivated among us; the latter is considered as an uncertain Crop—So. of New York and I have found it so on my farms—of the latter I have not made sufficient Trial to hazard an opinion of Success. About Philadelphia it succeeds well.

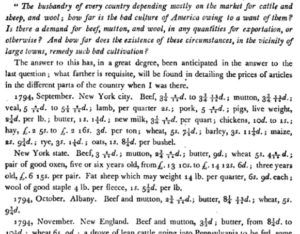

I haven’t yet laid a hand on a copy of his journal but in the 1800 publication from the British Board of Agriculture Communications to the Board of Agriculture, on subjects relative to the Husbandry, and Internal Improvement of the Country, there is an article starting at page 128 by Strickland “Observations on the State of America by William Strickland, Esq. of Yorkshire. Received 8th March, 1796.” In it you will see that it is actually a set of questions and answers. The questions were posed by the Board of Agriculture and were part of the purpose of his trip to the United States. Britain’s Board of Agriculture was set up in 1793, a private association which received a government grant to undertake research. The Board’s questions for Strickland were basic. What was the price of land in the young USA? What was the price of labour? Might not Great Britain be supplied with hemp from America? In response to the short questions, Strickland wrote pages. Not to ruin a good story with spoilers but his final paragraph on page 167 goes some way to remind us of the geographical limitations not only of his trip but of the young nation:

None emigrate to the frontiers beyond the mountains, except culprits, or savage back-wood’s men, chiefly of Irish descent. This line of frontier-men, a race possessing all the vices of civilized and savage life, without the virtues of either; affording the singular spectacle of a race, seeking, and voluntarily sinking into barbarism, out of a state of civilized life; the outcasts of the world, and the disgrace of it; are to be met with, on the western frontiers from Pennsylvania, inclusive to the farthest south.

Strickland’s America stretches form the Atlantic to the Appalachians. The other limitation we have to keep in mind is how little barley is mentioned in Strickland’s observations. As far as my search engine can tell, there is only the one reference in his observations to barley being sold in New York City in 1794 which sold at about 60% the price of wheat. Barley was not noted in the Albany market.

Look up there. We are well aware of the preference for wheat in the fields of New York. Wheat was worth far more and grew like a grain on steroids. Wheat was the basis of good beer in Albany of the 1670s and, under a decade after Strickland’s trip, the frontier brewery at Geneva, NY in 1803 was still cutting straw into the mash to cope with the high percentage of wheat malt being used. But Strickland was observing a new nation still coping with economic crisis. That Geneva brewery seems to have been established in 1797 in response to the crisis – with the promise of destroying “in the neighbourhood, the baneful use of spirituous liquors.” In New York the post-war economic collapse included depopulation of frontier* for much of the west of Albany as well as the blight of the Hessian fly. Upon seeing this, Strickland appears to be as happy to assist in the agricultural future of the new American republic as he was in reporting to the British Board of Agriculture. In his letter to Thomas Jefferson dated 20 May 1796 Strickland wrote a long passage about barley:

Where the improvement of the agriculture of a country can go hand in hand, with the improvement of the morals of a people, and the increase of their happiness, there it must stand in its most exalted state, there it ought to be seen in the most favourable light by the Politician there it must meet with the countenance and support of every good man and every friend to his country; so is it at present circumstanced in your country: by the cultivation of Barley your lands would be greatly improved; and the morals and health of the people benefited by the beverage it produces exchanged for the noxious spirits to which they have at present unfortunately recourse; besides the labour of the year would be more equally and advantageously divided, the grain being sown in the spring; but it was a striking circumstance that while the government was wisely encouraging the Breweries, in opposition to the distilleries the country should be entirely ignorant of the grain by which alone they could prosper; I have reason to believe that a grain of Barley has never yet been sown on the Continent; the grain which is there sown, under that name, is not that from which our malt-liquors are made; it is here known under the name of Bigg, or Bigg-barley, is cultivated only on the Northern Mountains of this Island, and used only for the inferior purposes of feeding pigs or poultry, and is held to be of much too inferior a quality to Make into Malt, and of the five different grains of the species of Barley known to us, it is held to be by far the worst; I have therefore taken the liberty of sending a small quantity of the best species of Barley, (the Flat or Battledore Barley) and the one most likely to succeed with you; this grain is sown in the spring, on any rich cultivated soil; I recommend it strongly to your attention; and shall rejoice if I prove the means of introducing into your country an wholesome and invigorating liquor.

Fabulous. Brewing was needed to civilize the community, to beat back the effect of rot gut whisky and Strickland saw that a key to this was the introduction of better classes of barley. Last year, Craig wrote about the difference between winter and spring barley in the second half of the 1700s and the transition away from a wheaty monoculture. He noted that “winter barley was euphemism for 6-row barley, and it was 6-row barley that would grow in tremendous amounts across western New York during the 19th and early 20th-centuries.” This week, Jordan colaborated on a brew with six-row barley, a recreation of an 1897 bock by Toronto brewer Lothar Reinhardt. But this is not the barley that Strickland was recommending. Notice he is recommending spring planted barley that is of far higher quality than six-row or what he calls bigg, the same coarser old form of barley his forefather was planting in 1568. In the generous and detailed corrections to the Oxford Companion to Beer – the wiki which was lost then found – a swath of beer writers prepared the following is stated at the letter “B” in response to the entry for “Bere (barley)” at page 123 of the famously troubled text:

“Bere (barley)” at page 123 states that “‘Bere’ has its origins in the Old English word for barley, ‘Bœr’.” The Old English word for “barley” was béow. (See Oxford English Dictionary at “bigg”). It further states that “It is synonymous with ‘Bygg’ or ‘Bigg’ barley, terms likely derived from the Norse word for barley, ‘Bygg’, which itself originates in the Arabic for barley.” The Norse word “bygg” does not originate in the Arabic word for barley. It has been suggested by some philologists (eg Bomhard and Kerns, The Nostratic Macrofamily, p. 219) that a word in the ancestor language of Arabic (and other languages, including Hebrew), Proto-Semitic *barr-/*burr, meaning “grain, cereal”, was borrowed by Proto-Indo-European as *b[h]ars-. Most philologists, however, derive bygg and bere (and barley, which, it should be noted, means “bere-like” – see OED at “barley”) from an Indo-European root *bheu to grow, to be (from which also comes the English word “be”), which gave a suggested proto-Germanic word for barley, *beww-, which became *beggw- in Old Norse, béow in Old English, bygg in Old Icelandic, and big in Norn (the language spoken on Shetland). It further states that “All of the Scandinavian languages used bygg for barley.” This is true only in the sense that the words in all modern North Germanic languages for “barley” are derived from “bygg” in their ancestor language, Old Norse, which was breaking up into its modern descendants around 1400. The modern Norwegian word for barley is still bygg, but the modern Danish is byg, the Swedish word is bjugg, the modern Icelandic byggi.

So, bigg as bygg goes a long way back. Excellent stuff. My only shame is that I forgot to transcribe over who in particular wrote that bit of correction. Sorry. In my grief over such a goof, I also sought some more detail in the section on barley in my copy of Ian Hornsey‘s 2012 book published by the Royal Society of Chemists Alcohol and its Role in the Evolution of Human Society but it turned out to be all about science and stuff. The sort of thing that did no good for my high school grade point average and which I appear to have passed on both genetically and behaviourally to the next generation of arts grads.

One bit of a conclusion, then, for now. We may be able to confidently state that when the new brewery in Cooperstown is looking for barley in 1795 and Gansevoort is looking for barley in 1798 they are very likely expecting to receive six-row, winter or bigg barley. Which makes some sense as it is likely a Dutch strain of barley, not English. Heck, look at the ad from John Mead in 1790 – he’s looking for rye, barley or wheat to brew with – anything he can get his hands on. That being the case, as Jordan has put into practice, recreations of historic northeastern North American barley beer from the period and perhaps for quite some time after need to be based on winter six-row barley and not the two-row spring barley William Strickland advocated for in the 1790s even though it was a far superior product. It was not, however, American – except around Philadelphia as George tantalizingly notes. More on that later.

*…aka the initial Anglo-American populating of Ontario.

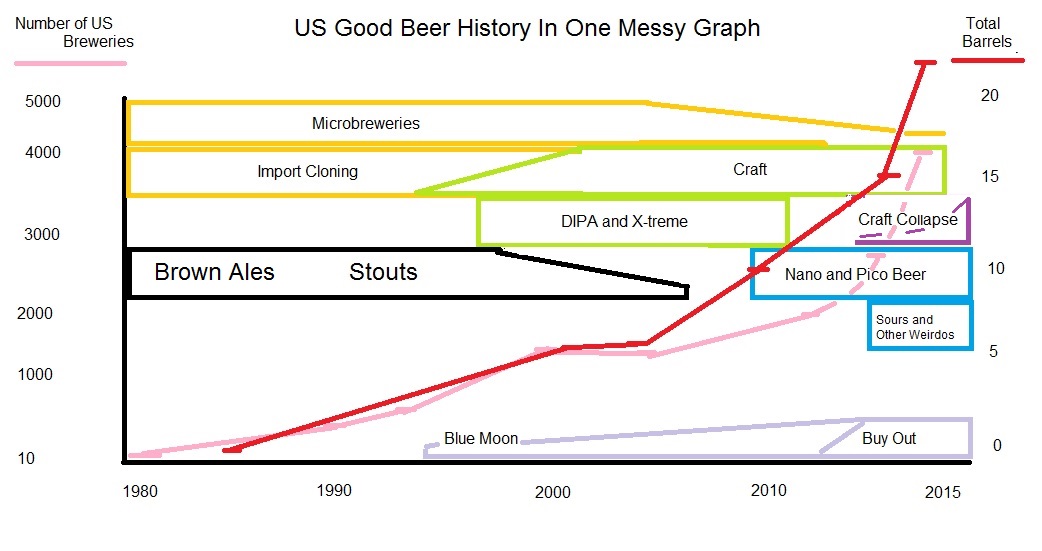

This post is just an excuse to post this picture from

This post is just an excuse to post this picture from