Attentive readers will recall that I have a slow side project in figuring out what I can about Taunton ale. It was a bit of a by-catch to the whole Albany ale thing with references to it showing up in central New York around the time of the American Revolution. When I got to the New York State Library in Albany in 2012, I found a mass of references to it being sold in New York in the 1750s and 1760s. And then it pretty much fell off the table. I couldn’t find anything more online. But three more years means three more years of people throwing everything they can find onto the Information Super Highway. So what is there to add to the story now?

Attentive readers will recall that I have a slow side project in figuring out what I can about Taunton ale. It was a bit of a by-catch to the whole Albany ale thing with references to it showing up in central New York around the time of the American Revolution. When I got to the New York State Library in Albany in 2012, I found a mass of references to it being sold in New York in the 1750s and 1760s. And then it pretty much fell off the table. I couldn’t find anything more online. But three more years means three more years of people throwing everything they can find onto the Information Super Highway. So what is there to add to the story now?

First, it was being exported to other parts of the British empire than just pre-Revolutionary New York. In 1774, Taunton ale is described as being one of Bristol’s exports to Jamaica along with products like West country cyder, cheese, leather, slate, grindstones, lead, lime for temper and Bristol water. Another record shows a ship for Jamaica in 1776 being loaded with Taunton ale, household goods as well as “volumes of entertaining history.” Taunton also is mentioned a number of time in The Bright-Meyler Papers: A Bristol-West India Connection, 1732-1837. In the entirely uncomfortably titled “Letters on the Cultivation of the Otaheite Cane: The Manufacture of Sugar and Rum; the Saving of Molasses; the Care and Preservation of Stock; with the Attention and Anxiety which is Due to Negroes and a Speech on the Slave Trade …”, what appears to be an 1801 guide to running a slave sugar plantation again in Jamaica, a warning is given on being too generous with one’s manager:

A very injudicious mode of remuneration, established by folly, and imitated by thoughtlessness, is that of fixed and stated presents. Such are, on many West Indian estates, invariably ordered for a manager, whether he is deserving of them or not; whether he makes fifty hogsheads, or five hundred; whether his Negroes increase or diminish; without regard to the situation of the stock, or to the improvement or neglect of any article entrusted to his care. These annual compliments consist sometimes of provision; as beef, butter, hams, and other articles of domestic consumption. But they are not judicious, even if they are merited. For their cost would invariably be turned to greater advantage, by an industrious economical manager, than the presents which are bestowed on him. Some of these acknowledgments, too, are pernicious in their nature: operate, though not intended, as an incentive to vice, and a seduction of the manager from his business. Such is the cask of Madeira before alluded to; and such are casks of porter and Taunton ale, with cases of claret. All these idle substitutes for judicious remuneration should be abolished, and proprietors should constantly reward their managers, in proportion to the services which they render, and the prosperity which they bestow, on whatever is entrusted to their care.

In 1808, a gazetteer states that large quantities of malt liquor called Taunton ale was also being sent to Bristol for exportation. Around the early 1820s, Taunton ale was selling in Bristol for 9s 6d a dozen quarts compared to 10s for Burton and 7s for porter.

Next, there is clearly a lifestyle aspect to Taunton ale in the beginning of the 1800s. It’s a beer for the destination traveling poet. Volume 30 of The Scots Magazine from 1777 included The Poem “In Praise of Tobacco” which included the lines “Say, Muse, how I regale, / How chearfully the minutes pass, / When with my bottle, friend, and glass, / Clean pipes and Taunton ale.” Yikes. In a 1797 letter, the clearly better poets Coleridge, Lamb and Southey are described as drinking Taunton along with a meal of bread and cheese. In the 1804 annual of Sporting Magazine, Taunton is described as most famous for that best of human beverage, good ale; though the author have I have before quoted thus mentions the attachment of the natives to it with some regret: “Hail Taunton! thou with cheerful plenty bless’d, / Of numerous lands and thriving trade possess’d, / Whose poor might live from biting want secure, / Did not their resistless ALE their hearts allure.” More bad poetry. Not sure how that reflects on the quality of Taunton ale.

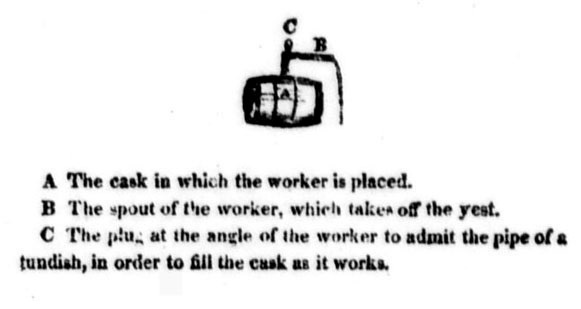

What was it? The 1824 booklet “The Spirit, Wine Dealer’s and Publican’s Directory” gives some sense of the beer in its treatise on “the art of making vinegar, cider, perry and brewing malt liquors – and particularly Taunton strong beer and ale.” We are told the strong ale takes eight or nine bushels of the best pale malt to the hogshead as well as six pounds of Farnham hops – but use east Kent hops if the beer is meant to be kept for two or more years. Strike at 160F, cover the lot with dry malt or sweet bran and let it sit for three and a half hours. Strain off and boil the wort with the hops of an hour. A half hogshead of strong ale results from the first running with ale and table ale the second and third. Its an odd sort of set of instructions for something written 191 years ago. It all reads a lot like a 1960s Amateur Winemaker home brewing article. The short guide recommends spirit dealers lower the proof of their rum by adding a mix of two-thirds water and one third Taunton strong for softness. It is a soft water zone so they may have had a point.

Also, Taunton seems to become the drink of a certain sort of well placed gent, especially when from one particular brewer. In Benjamin Disraeli’s letters from the mid-1830s, he tells a correspondent that Eales White would send a barrel of Taunton ale which he describes as “something marvelous.” The 1851 annual of Sporting Review describes the morning of a hunt and the reception in one great house:

The merry young sportsmen returned to the house, not however till they had been gratified by the safe arrival of the jumper, who, led by Thomas, was placed in a stall perfectly fresh and fit to go; by which time things were looking more cheerful. A bright fire blazed on the dining-room hearth; breakfast was prepared, the sideboard groaning with good substantial cheer; and even the somewhat flamingo-faced butler had contrived—knowing the squire’s peculiarity, or, I should rather say, punctuality on hunting mornings—to rouse himself from a most agreeable nap, and honour the lower dominions with his portly presence. In fact, as far as I can recollect, he was decidedly the most substantial, if not the most important, person of the Hall or neighbourhood – et pourquoi non? Excuse a French term, for he was certainly most useful in his special department; added to which, he brewed without exception the best ale I ever tasted: and if-so-be it precisely suited his own palate—what then? all the country round pronounced it undeniable. Stogumber beer was, or rather is, mere wish-wash in comparison, though vastly agreeable; and White’s Taunton ale alone could bear it any comparison.

Martyn cleared up the Stogumber question in 2011, but it is White which is clearly the name which appears associated with the best Taunton ale in mid-1800s English society. The report of Crimean Army Fund Committee of 1855 also mentions Eales White, Esq. of the Taunton Ale Brewery as a contributor to the cause among those who gave presents of wine, spirits or beer. Probate of the will of Eales White, Brewer of Taunton, Somerset was before the court in 1855. He has a rather splendid headstone.

And that is it. A beer for the bastardly late 1700s Jamaica slave plantation manager, for the great and crap poets of the turn of the century as well as for the gentry of the mid-1800s. Three dislocated bits of society, no? Well, they do sorta all have the well placed slacker theme going for them. Is that what the beer represented? The lazy entitled bastards’ reward?

Fabulous. I think my new best friend is Joseph Coppinger. Sure he published his book The American Practical Brewer and Tanner 200 years ago… but so few people come by these days I don’t care to notice such things. Like Velky Al did a couple of years ago, I came across an online copy of the book as I was looking for something entirely different. [No. No, not that.] And when I did I immediately – well, right after checking out the tanning section – noticed there were a number of recipes for beers. Styles of beers even. A listing of styles. In a two hundred year old book about beer. Odd. I thought that was invented in the 1970s by that Jack Michaelson chap. But, more importantly, he included this:

Fabulous. I think my new best friend is Joseph Coppinger. Sure he published his book The American Practical Brewer and Tanner 200 years ago… but so few people come by these days I don’t care to notice such things. Like Velky Al did a couple of years ago, I came across an online copy of the book as I was looking for something entirely different. [No. No, not that.] And when I did I immediately – well, right after checking out the tanning section – noticed there were a number of recipes for beers. Styles of beers even. A listing of styles. In a two hundred year old book about beer. Odd. I thought that was invented in the 1970s by that Jack Michaelson chap. But, more importantly, he included this:

Attentive readers will recall that I have a slow side project in figuring out what I can about Taunton ale. It was a bit of a by-catch to the whole Albany ale thing with references to it showing up in central New York around the time of

Attentive readers will recall that I have a slow side project in figuring out what I can about Taunton ale. It was a bit of a by-catch to the whole Albany ale thing with references to it showing up in central New York around the time of