I picked up this beer while on the road and I was immediately in a fix, dealing with cultural confusion. As a son of Scots I know that Belhaven is a fine and reputable brewer of Scots ales bought last year by Greene King… yet I know IPA is not a Scots style. I have discussed this before in relation to Deuchars IPA but this beer – or more particularly the comparison between the two beers makes their labelling as IPAs a wee bit problematic.

I picked up this beer while on the road and I was immediately in a fix, dealing with cultural confusion. As a son of Scots I know that Belhaven is a fine and reputable brewer of Scots ales bought last year by Greene King… yet I know IPA is not a Scots style. I have discussed this before in relation to Deuchars IPA but this beer – or more particularly the comparison between the two beers makes their labelling as IPAs a wee bit problematic.

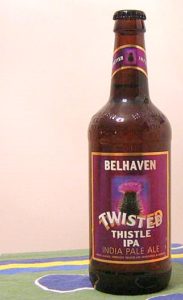

Look – here is what I thought about Twisted Thistle. When I had it the other night I wrote:

Caramel ale under light tan foam and a thick cling and ring. A very fruity ale, berry fruity but mainly crusty sweet country loaf of bread. Rich with some smokiness and creamy yeast. Then it opens into light dry fruit apple and raisin with a note of honey. Grapefruity hops balance but in a recessed position, a subordinate role. Definitely more like a pale ale in the zzap-tastic north-east US scale. But richer.

Then note what I concluded about Deuchars in October 2004, a year and a half ago:

You can see they are really different ales, Deuchars being is light and crisp while the Belhaven IPA was to my mind more like a Bombardier with a lighter touch on the same heavy elements, especially the dry fruit characteristics – dry apples and light raisin rather than, say, figs and dates but still dry fruit.

Don’t get me wrong. Both are good bevvies you should try. My point is IPA is becoming a very broad term, so broad I am finding it a little meaningless as an indicator of what I will find when I pour the bottle. Terms like “stout” and “mild” or “dubbel” do not generally pose this problem for the thoughtful buyer facing a new beer. It reminds me a bit of white wine and the labeling of them according to grape varieties which became popular in the early 1990s. People then came to say they like Chardonnay or Merlot but then were surprised when this Chardonnay or that Merlot was nothing like the wine they could they recognized. Like with IPA, too much is due to the actual wine making techniques for the comfort of those wine drinkers relying on the label for guidance. Key terms then become the opposite of what they were meant to be – they come to deter rather than attract.

So try Twisted Thistle. It is not a Scots style /80 or wee heavy or an IPA or like Deuchars IPA. But it is really really pleasant.

[Original comments…]

Joe – April 26, 2006 9:56 PM

http://unabrewer.com

“…yet I know IPA is not a Scots style.”

These specific beers and the accuracy of the IPA descriptor aside, I don’t see why a Scottish brewery couldn’t make an IPA. Americans make IPA’s, Imperial Stouts, and Doppelbocks. I think aside from protected names (like champagne) and things like lambic that literally rely on local microcosms, you can make anything anywhere.

And even in those specific instances, I don’t have a problem with a brewery labeling a beer “lambic-style” or some such nomenclature as long as the beer is an honest attempt at the style flavor. This, of course, ties in with the end bits of your post.

Alan – April 27, 2006 7:59 AM

I think they could make an IPA but should they make anything and call it an IPA? What is the limit on the usefulness of branding something a most popular style when it starts to move away from the characteristics of that style? This is my question – even when the fluid is question is excellent as in this case.

Knut – April 27, 2006 9:54 AM

http://beerblog.motime.com

To add to the confusion Greene King has a bottled bitter which they call IPA, too. (It is available on draft in Britain and exported bottled.) The same goes for that one – a nice soft ale, but why the label IPA. Was there a more hoppy version which has been softened down?

Alan – April 27, 2006 11:56 AM

What is wrong with “best bitter” and “pale ale”? These are great words for labels.

Ron Pattinson – May 2, 2006 10:44 AM

British definitions of beer styles are generally much looser than in North America. “Bitter” can cover a very wide range of strengths, flavours and even colours. As IPA is usually used as a synonym for Bitter in the UK, I can´t see any problem in using it to describe a beer that falls within the parameters of a Bitter. It might not be very precise, but it fits in with British usage.

Modern Bitter probably developed from at least two different older styles:

– IPA/Pale Ale

– AK/Dinner Ale

Originally there was a large difference in strength between the two: IPA at around 1065 and AK at 1045. As taxation drove down beer strengths in the early 20th century both ended up at around 1040. (If you want my opinion, modern Bitter is much closer in character to AK than IPA.)

Other British styles are equally vague. Mild can be anything from pale amber to black in colour, between 2.8% and 6% ABV, sweet or dry, even roasty or hoppy. Old Ale, Barley Wine and Stout all have a wide range of variation.

In North America beers are divided into much narrower more tightly defined categories. Which is why there are so many more classes in the GABF competition than the GABF. A different philosophy most likely dictated by very different histories of the two brewing cultures.

Alan – May 2, 2006 11:12 AM

If you look at Terry Foster’s book Pale Ale he says bitter and pale are the corresponding English terms, not bitter and IPA. Terry is an Englishman in the USA to compound the problem. I think it is fair to say that traditionally in England there were gradations of pales and stouts with an understanding that so many X’s or “extra” on the label meant a specific thing to the consuming public and the brewer’s competition.

Maybe what has happened is that UK useage of these terms has actually slipped more than the US one has due to the US really being new to them. I was also thinking of another comparison – Belgian beers. I would have a hard time confusing a dubble for a dark strong as there is a rigourous attention to the one or two key ingredients that make the difference between the two styles. I am not a style fan for style in itself but I think they should have some meaning and that the traditional meaning (if one is available) is likely the best.

Ron Pattinson – May 2, 2006 11:49 AM

X´s were used for Mild and Stout, not usually for Bitter Beers. These were identified by a variety of names, though the stronger ones sometimes used a number of K´s.

This is the family of 19th century British Bitter Beers:

Table Beer 1040

Dinner Ale or Luncheon Ale (or later Light Ale) 1045

AK or BB (Bitter Beer) 1050

Pale Ale 1055

IPA 1065

KKK Keeping Beer 1080

KKKK Keeping Beer 1090

Barley Wine 1100

Gravities are for the period 1880-1900.

Ron Pattinson – May 2, 2006 11:51 AM

Almost forgot. Pale Ale was the term used by breweries, Bitter by drinkers. Many older breweries still officially call their Bitter PA. This dichotomy goes back to at least the 1880´s.

Alan – May 2, 2006 12:00 PM

Foster cites a draught (bitter) and bottle (bottle) distinction. There are lots of examples of bitter being used on the label but I think you are right that “bitter” likely arose from the experience of the beer as it is descriptive in the way that “mild” is. “Pale ale” would be a brewers branding concept to distinguish it during its early days from the brown-ness of the browns.

Ron Pattinson – May 2, 2006 6:12 PM

Sometime in the 19th century – I’m not sure when – drinkers started ordering “bitter” in pubs. The beer they usually meant was some sort of Pale Ale. The brewery probably called it either Pale Ale or India Pale Ale. Looking at the Good Beer Guide (these are taken from the 1983 edition), you’ll notice how some of the teminology has, at least within breweries, survived WW II.

King and Barnes: XX (mild), PA (bitter), XXXX (old ale)

Harveys XX (mild) PA (bitter), BB (best bitter), XXXX (old ale)

Greene King XX (mild), KK (light mild), IPA (best bitter)

Ridleys XXX (mild), PA (bitter)

Traditionally, Bitter rarely appeared on beer labels, where the names Pale Ale or Light Ale were preferred. It was much the same with Mild, which usually got called Brown Ale in bottles, or even things like Family Ale.

But back to 19th boozer. Why did drinkers use the word “bitter”? It could have been descriptive. “Bitter Beer” is also the generic name for a whole range of styles, that encompasses both Pale Ale, Strong Keeping Beers and low-gravity beers such as AK. 19th century brewery price lists are often divided into 3 sections:

– Porter

– (Mild) Ales

– Bitter Beers

It’s easy to imagine customers ordering “porter”, “mild” or “bitter” as simple shorthand for the cheapest version of that generic type. In a time before pumpclips and when there were loads of breweries, usually with large product lines (4 porters, 4 milds, an Old Ale, an IPA, a Table Beer is about the minimum), it’s easier than trying to guess whether a pub sells IPA, KK or KKK. Or whether they have the XX or XXX Mild on. Porter and Mild have certainly both been used this way.

There was a strong distinction in England between Beer and Ale for centuries after the introduction of hops. Even for centuries after Ale had started using hops, the difference in the amount used was still enough for there to be a clear differentiation between the two. 18th century brewing manuals use the terms “Beer”, “Ale” and “Malt Liquor” (the generic term for both Ale and Beer) in a very specific sense. In general, beers were hopped at about 4 times the rate of the corresponding strength ale (“London & Country Brewer”, 1736 p.73). In London, the official barrel sizes were even different – 32 for Ale, 36 for beer – until 1819.

The division of beer styles into 3 generic groups dates from the introduction of Porter in the 18th century. Though originally it was classed as a “Brown Beer”. It’s specific qualities (and, no doubt, the large number of varieties produced) eventually saw it considered a third generic style. Porter was used to mean both the weakest beer of the type and the type as a whole, i.e. all Porters and Stouts. Much later, when Porter was in terminal decline (I think some time around 1900), the term “Black Beer” was coined.

Of course Pale Ale, in 18th century terms, is a Pale Beer. I guess as the distinction between Beer and Ale faded, they just went with the one that sounded better.

Mild didn’t refer to the taste, either. It meant unaged, until at least the 1860’s. It’s the “Ale” in Mild Ale that tells you it’s not bitter. You also had Mild Porter, hopped at 2-3 pounds per (36 gallon) barrel, so quite bitter (“The Brewer” William Loftus, London, 1863 p.47). IPA was hopped at 6 pounds per (36 gallon) barrel in the copper, with another 2 pounds per barrel as dry hops after racking (“The Brewer” William Loftus, London, 1863 p.45).

Alan – May 2, 2006 7:44 PM

I think I disagree with a few of your facts but in a recreational way – so here is my understanding based on my contrasting sources:

Until the 1870s at least porter and lild battled for supremacy in the London area. A visitor to Cobb’s Margate Brewery in 1875 remarked, “It is strange how the taste…for old stale beer has turned to the opposite extreme in the liking for mild and sweet by the present generation.” But by 1890, the trend turned away from vatted porter which itself was becoming more and more “mild,” in that it was vatted for a much shorter time – time – sometimes as little as two months! towards the sweeter and less tart mild ale. One chronicler of the brewing industry noted that “the fickle public has got tired of the vinous flavoured vatted porter and transferred its affections to the new and lucious mild ale.”

I am not so certain that mild is a continuation of ale given the gap in centuries between mild’s mid-1800s popularity (after the porter boom) and beer’s triumph over beer in the Renaissance. In England, the barrel sizes were for tax purposes, trade protection and consumer identification to distinguish between fast deteriorating ale from longer storing hopped as of the late 1400s according to Unger at pages 97 to 103. As to the end of ale as an unhopped brew he states at 103:

An English writer on hops in 1574 simply said that his countrymen had given up ale for beer, so a victory had been one, but the war was not over. Packets of ale making held out in England as it did in northern Europe for some time.

But your fact that the 32 and 46 gallon division existed to 1819 is interesting. Where is that source? Is it an old rule on a book not applied or was it transferred from ale brewing to one sort of beer as opposed to other beers.

Foster shows a label in Pale Ale for a bottle of Burton Bitter Beer and also quotes, at page 17, Michael Jackson as stating of “bitter”:

its acceptance as a formal stale is relatively recent, and the name “bitter” may not have been fully established as late as the 1940s. Foster also suggests the possibility that the same beer from Burton was a bitter and elsewhere was pale ale.

India Pale Ale is a sub-set of pale, a specific condensed form for the military trade India (and other export desitinations) where (I believe but not yet certain that) it may have been intended to be watered down only later to be drunk in its full concentrated form in England, legend has it, after a ship wreck when some village got a taste for it. But a Mr. Hodgson pretty initiated the style based on his monopoly of supplying the British military ending in the 1820s. Here is wikipedia’s take on IPA…for what it is worth!

So interesting facts but hard to get a handle on them. Martyn Cornell in Beer: the Story of the Pint states at page 145:

Certainly IPA’s spread in Britain coincides with the growth in what was called variously in the 1840s and 1850s “bitter ale”, “pale ale” and “bitter beer”. Pale ale and bitter are effectively the same drink, pale ale being the brewer’s designation, bitter being what the customer called it in the pub.…[gotta run…edit later…]

Ron Pattinson – May 2, 2006 10:49 PM

I base everything that I say on primary sources. All written before 1918. You have to be very careful about relying on other people’s interpretations of old texts. The terminology can be difficult to understand and I disagree with many interpretations I have read.

I interpret this quote:

>Until the 1870s at least porter and lild battled for supremacy in the London area. A visitor to Cobb’s Margate Brewery in 1875 remarked, “It is strange how the taste…for old stale beer has turned to the opposite extreme in the liking for mild and sweet by the present gneration.” But by 1890, the trend turned away from vatted porter which itself was becoming more and more “mild,” in that it was vatted for a much shorter time – time – sometimes as little as two months! towards the sweeter and less tart mild ale. One chronicaler of the brewing idustry noted that “the fickle public has got tired of the vinous flavoured vatted porter and transferred its affections to the new and lucious mild ale.” agrees with what I said. Note the phrase “mild and sweet” – mild = not matured for long, sweet = not bitter. It even says “mild” porter wasn’t matured as long. OK, mild implied not sour, but it didn’t mean not bitter. “London & Country Brewer” was published 1736. It talks about Beer and Ale and defines exactly the difference between the two. It uses the words very precisely. It says:

“Ale, which to preserve in its mild Aley Taste, will not admit of any Great Quantity of Hops.” (p.37) “All good Ale is now made with some small mixture of Hops, tho’ not in so great Quantity as Strong Beer” (Directions for Brewing Malt Liquors” London , 1700)

Ale never disappeared, it just adapted (using some hops) to changed conditions.

Hopping rates from “London & Country Brewer” p.73:

– Strong Brown Ale one pound per hogshead (48 gallons)

– Pale Ale 1.25 pounds per hogshead (48 gallons)

– October or March Brown Beer 3 pounds per hogshead (54 gallons)

– October or March Pale Beer 6 pounds per hogshead (54 gallons)

It’s clear that the Pale Ale described here has little in Common with that of the 19th century. The description of brewing “Stock Beer” in The Brewer (p.37) is very similar to that of October or March Pale Beer in “London & Country Brewer”.

“Beer, brewed and vatted entire, in the months of March or April, will probably be fit for consumption in the following Spring; but that brewed in October may need two seasons to bring it into condition” (The Brewer p.37)

On the British Library newspaper archive site there’s an article from the Weekly Dispatch from April 1917. It’s an article (amazing so far into the war) about horrific increases in the price of beer. It lists various beer types (it’s referring specifically to London) and the retail price per barrel:

Porter 100 shillings

(X Ale) Mild 100 shillings

Stout 140 shillings

Bitter 120 shillings

Burton 150 shillings

Another Weekly Dispatch article, from September 1917 quotes beer prices in Woolwich:

Glass of beer 5d

half pint of bitter 6d

bottle of Bass 8d

bottle of stout 9d

drop of whisky 5d

It also talks about “a mixture known as mild and bitter”

The Daily News of February 1st 1856 has an Allsopp’s advert. It gives prices for Allsopp’s Pale Ale, Allsopp’s Mild Ale and Allsopp’s Burton Strong Ale. There are then a series of testimonials from doctors for Allsopp’s Pale Ale:

“Order my patients Allsopp’s bitter beer with marked advantage” – Dr. Richard Formby.

“I recommend bitter ale medicinally” – Sir Charles Clarke, M.D.

“Of a nutritive and stomachic character; can safely depend upon Allsopps’s bitter beer.” – Dr. James Petrie.

“A mild, bitter, and pleasant beverage, for giving increased impetus and vigour to a weak and low stomach.” Dr. William Guy.

It strikes me that “Pale Ale”, “Bitter Beer” and “Bitter Ale” are being used interchangeably here.

“The Brewer” by William Loftus has a chapter entitled “India Pale Bitter Ale” (p.43-45).

Michael Jackson is wrong, the term bitter is much older the the 1940’s.

If you want to see some old texts, this has a few transcripts:

http://www.jbsumner.com/pages/brewinghistory/transcripts/

in Accum (written in 1820) there is a section explaining the difference between “Old, or entire; and mild, or new beer”. I have seen no instance before 1870 where “mild” was used to mean anything other than young.

My source for barrel sizes is:

1819 Weights & Measures Act:

A barrel of beer, in London, contains, by a Statute of Charles 2, 36 a barrel of ale 32; but out of London, a barrel both of ale and beer was directed to contain 34 gallons, by a Statute of William and Mary. The distinction has been abolished by a late Act, which directs that all barrels, both of ale and beer, in town and in the country, shall contain 36 ale gallons.

This is a web source:

http://www.sizes.com/units/barrel_alebeer.htm

Ron Pattinson – May 2, 2006 11:31 PM

http://www.xs4all.nl/~patto1ro

Just found another one:

“Superior Porter, 12d; Imperial Stout, 18d; India Bitter Ale, 10d per gallon” News of The World, Jan 12th 1851.

This is another beer from an 1870 advert:

“Bedford Brewery AK – a mild bitter ale”

I just love the combination of mild and bitter in one beer description.

Alan – May 3, 2006 9:05 AM

I am quite content not to deal with primary sources especially in the beer industry as most of the good stuff in the period we are talking about sits in private brewery libraries. And I, like you, am also not a historian – unless you inform otherwise.

You need to fix your claims to terminology within trends in language as well – what did “mild” mean in general usage in 1780 or 1840. That is the benefit of the quotation from Sutula. It contextualizes. Plus you are saying that ale as a fluid continued in a form which is interesting but the only interpretation of that kind I have seen. What really appears to have occurred is the continuation of the name “ale” with something that was not “ale” – hopped beer. With respect, it is not clear and others are not wrong, though it is very interesting and adds to the discussion. All sources tend to agree there is much uncertainty.

Alan – May 3, 2006 9:08 AM

I would be interested to know more about the 1819 regulation on barrels as that period had much reform in all English law. As I studied in law school, many medieval and Renaissance regulations were abolished in that period. That the rule still existed about ale barrels does not mean ale was being put in barrels anymore than Gypsies could only be met in the street when one was in the presence of a priest – as was the law from the 1500s existed in most of the British Empire until around 1840.

Ron Pattinson – May 3, 2006 10:33 AM

The sources I quote are not that difficult to obtain. “London & Country Brewer”, “The Brewer” and “Directions for Brewing Malt Liquors” are all on the web. As are the newspaper quotes and the Accum transcript. They are all infinitely more valuable than information filtered through other writers.

If you are going to trust anyone, I would stick with Martyn Cornell. He does base his writing on primary sources and knows what he´s talking about. I like this quote from him “Second, I set out deliberately to ensure an accurate account, to destroy the dozens of myths that have encrusted the history of beer, with one chapter devoted to some of the worst errors.”

Another good place for info on 18th and 19th century beers is “Old British Beers and how to make them” a book which is still in print.

>You need to fix your claims to terminology within trends in language as well – what did “mild” mean in general usage in 1780 or 1840.>

It´s irrelevant. Mild had a very specific meaning in realtion to brewing. Try reading the Accum transcript. If “mild” means “not bitter” how do you explain phrases such as “mild bitter ale” or “A mild, bitter, and pleasant beverage”?

If you want I can send you the text of “London & Country Brewer”. Read and then tell me that Ale didn´t exist in the 1700´s. In the recipes the Ale volumes are gibven in barrels of 32 gallons. Yes, they really were filling it into Ale into Ale barrels. The law on barrel sizes was changed in 1688:

“In 1688 (1 William and Mary chap. 24, s 4)1, the barrel of both beer and ale was set at 34 ale gallons. (London, however, persisted in using a 36-gallon beer barrel and a 32-gallon ale barrel.) The barrel of vinegar was also made 32 gallons.”

http://www.sizes.com/units/barrel_alebeer.htm

I understand old laws lie around on the statute books, but why formulate a new one that refers to something that no longer exists?

What about this quote:

“All good Ale is now made with some small mixture of Hops, tho’ not in so great Quantity as Strong Beer” (“Directions for Brewing Malt Liquors” London , 1700)

If Ale didn´t exist, what the hell does this statement mean?

There are other examples of pre-hop styles continuing after the introduction of hops and using a small amount themselves. Keut and Grussink from Munster are good examples. Keut (a late medieval gruit beer also brewed in Holland where it was called Koyt) continued to be brewed in Munster right up until the end of the 1800´s. In such beers hops were primarily used for their preservative properties rather than as a flavouring.

Do you agree that the term “bitter” was probably in common use well before 1940?

Ron Pattinson – May 3, 2006 10:55 AM

http://www.xs4all.nl/~patto1ro/

You can find the text of “London & Country Brewer” here:

http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/gutbook/lookup?num=8900

Alan – May 3, 2006 2:25 PM

As with much of the above, Ron – and please don’t take it to be rude – but I know all that. But I am goint to take Unger’s word on ale over yours. I take professional beer writers research over yours. I take all the other writers on the gap between ale and mild over your understanding of use of the word “ale” to mean the same substance. I know where to find “London & Country Brewer” but do not know that the substance it might refer to as “ale” is the same in both 1550 and 1850 and suspect the private libraries have much better information.

Your discussion is only based on your amateur take on advertising and a few texts as far as you have explained it. There may be more but I am not yet convinced. With respect, I can’t take that as worth anything more than your hobby interest and opinion. Those are good things but not compelling in light of other information. They are, however, interesting.

Ron Pattinson – May 3, 2006 2:54 PM

Fair enough.

Don’t take this as bein rude, but if you can’t be bothered to check the texts I’ve suggested, I can’t see much point in having a discussion.

I have no monopoly on the truth. I’m sure plenty of what I say isn’t quite right, or just plain wrong. But my views are based on probably more research than you realise.

Sherlock Holmes was an amateur.

Alan – May 3, 2006 3:02 PM

I did check the texts. You have not made a compelling argument, that’s all. It is interesting and there are interesting bits but you have to present your information in a way that is more pursuasive if you are to draw me away from all that I have read and towards your position. I have nothing against the amatuer as I am one, too. But I know that I spend 0.01% of the time devoted to the topic compared to those I rely upon for their best guess.

Ron Pattinson – May 17, 2006 5:17 PM

Interesting page on the CAMRA website about Bitter:

”

Bitter

Bitters developed towards the end of the 19th century as brewers began to produce beers that could be served in pubs after only a few days storage in cellars. Bitters grew out of pale ale but were usually deep bronze to copper in colour due to the use of slightly darker crystal malts.

Towards the end of the 19th century, brewers built large estates of tied pubs. They moved away from vatted beers stored for many months and developed ‘running beers’ that could be served after a few days’ storage in pub cellars. Draught Mild was a ‘running beer’ along with a new type that was dubbed Bitter by drinkers. Bitter grew out of Pale Ale but was generally deep bronze to copper in colour due to the use of slightly darker malts such as crystal that give the beer fullness of palate. Best is a stronger version of Bitter but there is considerable crossover. Bitter falls into the 3.4% to 3.9% band, with Best Bitter 4% upwards but a number of brewers label their ordinary Bitters ‘Best’. A further development of Bitter comes in the shape of Extra or Special Strong Bitters of 5% or more: familiar examples of this style include Fuller’s ESB and Greene King Abbot. With ordinary Bitter, look for a spicy, peppery and grassy hop character, a powerful bitterness, tangy fruit and juicy and nutty malt. With Best and Strong Bitters, malt and fruit character will tend to dominate but hop aroma and bitterness are still crucial to the style, often achieved by ‘late hopping’ in the brewery or adding hops to casks as they leave for pubs.”

http://www.camra.org.uk/page.aspx?o=180668

Ron Pattinson – May 17, 2006 6:56 PM

This is from the Coors (former Bass) Museum website:

http://www.bass-museum.com/hr_data_content.asp?section_id=25&item_id=23

“The origins of Draught Bass date back to the early 1820s. Before that time Bass, like the other Burton brewers would have been brewing a dark, heavy, high gravity porter for export to the Baltic markets, as well as for local consumption.

In the 1820s the Burton brewers began to experiment with a new product, a pale ale, which had been successfully developed by Mark Hodgson, a London brewer. This pale ale with its excellent keeping qualities proved ideal for the expanding colonial markets, being bright, sparkling and thirst quenching. It therefore became known as India Pale Ale (I. P. A.).

Today’s Draught Bass is a direct descendant of this I. P. A., although the gravity has weakened considerably, largely due to the increase in the amount of duty imposed during World War I. In the 19th century its gravity averaged 1062º (6.2%) falling to 1044º (4.4%) in 1919 and settling at about 1046º (4.6%) in the 1950s.”

(In the 2006 Good Beer Guide it’s listed as 1043 4.4% ABV)

It’s a shame the changes during WW I aren’t better documented on the net. It would be interesting to see average gravities 1900-1950.

Alan – May 17, 2006 7:32 PM

The internet doesn’t even document the 1990s well!

The reference above does not mention Burton ale which is a separate thing and really only exemplified by Sammy Smith’s winter warmer. It is referenced in Wind in the Willows.

Alan – May 17, 2006 9:33 PM

No, I meant Sammy’s but Young’s is there as well. Ballentine’s in New England also had a Burton ale but that might have been a reference to the IPA. If you look here there is a good discussion I had with Martyn Cornell on Burtons and Wind in the Willows back in 2003. He notes that the original illustration in the book included a bottle of Bass.

I think your point about historical stats is possible by joint effort on the internet but there is also the problem of categorization: is one firm’s table ale the same as the next one’s. Is there even a good generally available reference even to brands brewed over a period of time? Like the Encyclopedia of Baseball, just the stats.

Alan – May 18, 2006 8:06 AM

I think your point about cask ale kicks in. I have to say the favorite pale ales of mine are local to me. There is a great difference between the bottle and the bung. The pales I have had in Syracuse NY from the microbrewers there of Portland Maine are among the best I have ever had. But that being said, my recent taste of Pitchfork Bitter was quite the thing. But as to actual sub-4% bitters I have had? Again, the best were the ones I used to make myself if only because they otherwise do not really exist on this side of the Atlantic.

Ron Pattinson – May 22, 2006 5:52 AM

What about Best Bitters then? Which of those have you tried?

I would pick these.

Holts Bitter – an aggressively bitter, dry beer, very typical of the Northwest.

Brakspear´s Special – aromatically hoppy with a distinctive character from the “double drop” fermenters.

Arkell´s 3B – a typical Southwestern bitter with a rich, malty base, some balancing hops and a honeyish finish.

Marston´s Pedigree – has a challenging “Burton snatch” aroma, followed by delicate British hops. The last classic Burton bitter brewed in unions.

Knut – May 24, 2006 9:24 AM

http://beerblog.motime.com

London Pride and Young’s Special for me. But the ales from St Peter’s, including their bitters, are amazing. I’ll go straight to the Jerusalem Tavern next time I’m in London!

Paul – November 18, 2007 2:41 PM

Hello there,

I have a question that has been bugging me for a long while… I left the UK (London) about a year ago and am trying to remember the name of a beer that I drank only a few times, but I really liked it. Perhaps you can help me out:

It was in a dark blue or navy blue can and had a big X on the front. Does that ring any bells?

At first I thought it was “Marstons X” but I have not been able to find that anywhere online…

Thank you very much

Paul.

PS I live in Canada now, and would like to know your impressions of Canadian beer – great blog!