It seems like a very sad thing. As Mr. Beaumont has already pointed out, for a global beer blogging day, the very question asked is so provincial, so singularly parochial and limited to one nation of all the nations of the world that one has to take it either as an intentional insult or at least as an approach so laced with ignorance that one inevitably wonders whether to take up the challenge or not. That is no less the case when one considers that the question is being posed by a craft brewery that brands itself so closely in relation to the question of the US national repeal of prohibition, 21st Amendment Brewery of San Fransisco. Frankly, I feel as if I am writing their advertising copy for them which I trust was never ever the intention of The Session and should be a call (again) to get this day a month back on point…and that point being beer.

But having said all that (and keeping in mind I am extra cranky due to being off work sick) as the folk asking the question today are by all accounts a wonderful, witty and wise gang of malt jockies as ever there was – oh, what the hell. So, as any good legal counsel as I presume myself to be would, let us begin from the beginning. The full inquiry posed by 21AB is this:

What does the repeal of Prohibition mean to you? How will you celebrate your right to drink beer?

Well, the obvious answer to the first is absolutely nothing whatsoever. I wasn’t around then and pretty much anyone that was is dead and never met me. The second is really disconnected. As a right, it is something that is inherent to me as a human being and not something granted or retracted by the state. This is something neocons and, in the US, those called “originalists” get but really don’t get. A right cannot be defined by a constitution – it can only be observed to be present and acknowledged by the state through declaration and then respect. The wisest constitutions and constitutional thinkers realize that the observation and recognition of rights is not unlike the job of the tropicial ecological taxonomist: when a new species of bird is identified, it gets noted down, its characteristics observed and it is given a name. It is respected for what it is and also understood to have been pre-existing. So, too, with any observed right and the control of alcohol is a splendid example: in both the respect and disrespect implicit in regulation of booze-related rights. It is worth noting again that we have to separate right from regulation and thing about each separately and in their relation to one another. Notice also that I stated this in the present tense. We will reflect again on the question “what does the repeal of Prohibition mean to you?” As you will see, I argue that we are not done with it today.

More about law. We are discussing the “repeal” of a certain thing. That happened on a date. That it was not actually this date or that date in the US nor this date in many other dates in all the other places where a prohibition on alcohol was or has been in place is not important. In fact, in many places and in many ways it still exists. What is important is that the certain thing being “repealed” is a “prohibition” – the stopping of doing of an activity by action of law. That last bit that is important, too: “by action of law.” You see, prohibition by law is not actually the stopping. Murder and theft are illegal and happen, sadly, every day. If you think about it, those lucky enough to live in free states are in fact largely free, in a way, to do wrong but then are also subject to the sanction of law and the punishments imposed under those laws. So to understand what we are even talking about today, we need to understand two basic things: what is the right being discussed and what did the law do when it prohibited. Once we know that, we can discuss a third thing – what effect did the law actually have…because we all have to admit all laws are subject to their own inherent stengths and weaknesses as well as different rates of success.

More about law. We are discussing the “repeal” of a certain thing. That happened on a date. That it was not actually this date or that date in the US nor this date in many other dates in all the other places where a prohibition on alcohol was or has been in place is not important. In fact, in many places and in many ways it still exists. What is important is that the certain thing being “repealed” is a “prohibition” – the stopping of doing of an activity by action of law. That last bit that is important, too: “by action of law.” You see, prohibition by law is not actually the stopping. Murder and theft are illegal and happen, sadly, every day. If you think about it, those lucky enough to live in free states are in fact largely free, in a way, to do wrong but then are also subject to the sanction of law and the punishments imposed under those laws. So to understand what we are even talking about today, we need to understand two basic things: what is the right being discussed and what did the law do when it prohibited. Once we know that, we can discuss a third thing – what effect did the law actually have…because we all have to admit all laws are subject to their own inherent stengths and weaknesses as well as different rates of success.

First, then: what is the right. There is a principle in the Canadian constitution that I explored in my chapter on our relgulation of beer found in the book “Beer and Philosophy” which came out just last year (and so still makes an excellent stocking stuffer.) That principle states:

“everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.”

The first thing you will see as that this is a set of rights and it is not a statement of the grant of the rights but an acknowledgement. It is also a balancing. The right not to be deprived is conditional on “the exercise of the principles of fundamental justice”. The meaning and elaboration of these right have been explored many times by many courts and, in 2003, an aspect of the right to liberty – which we can call the sub-right of “autonomy” or the right to be left alone – was discussed by the Supreme Court of Canada in the case R. v. Clay in relation to marijuana use. The court, illogically as I suggested at the time, stated that:

…the liberty right within s. 7 is thought to touch the core of what it means to be an autonomous human being blessed with dignity and independence in “matters that can properly be characterized as fundamentally or inherently personal” With respect, there is nothing “inherently personal” or “inherently private” about smoking marihuana for recreation. The appellant says that users almost always smoke in the privacy of their homes, but that is a function of lifestyle preference and is not “inherent” in the activity of smoking itself. Indeed, as the appellant together with Malmo-Levine and Caine set out in their Joint Statement of Legislative Facts, cannabis “is used predominantly as a social activity engaged in with friends and partners during evenings, weekends, and other leisure time” (para. 18). The trial judge was impressed by the view expressed by the defence expert, Dr. J. P. Morgan, that marihuana is largely used for occasional recreation.

What boggles my mind about this ruling is the idea that one’s private pleasures in life – which are often the things which one actually takes most joy from in life and most makes oneself known and identifiable to oneself – are not protected. I think this is wrong. The court confuses “fundamentally or inherently personal” with matters which are objectively or, worse, collectively accepted as serious. Put it this way, a fan of craft beer who spends a large measure of income on the interest and is fascinated enough by the subject to, you know, blog about it pretty much every day and even write chapters in books about its regulation likely also considers it “fundamentally or inherently personal”. I will not digress further on this point but to note the case was not on booze and if it was on the issue relating to a lawyer’s wine cellar, the court might have had other sympathies – and the difference between wine and marijuana might well justify such a difference. Suffice it to say, however, that this is a reasonable example and description of the underlying human right as against the state that is at play when we are talking about Prohibition in this context. And, if we thing of our tropical ecological taxonomist above, the name of that right is “autonomy.” So, having established the nature of the right, we can now move on to the question of the nature of what is “prohibition”.

What boggles my mind about this ruling is the idea that one’s private pleasures in life – which are often the things which one actually takes most joy from in life and most makes oneself known and identifiable to oneself – are not protected. I think this is wrong. The court confuses “fundamentally or inherently personal” with matters which are objectively or, worse, collectively accepted as serious. Put it this way, a fan of craft beer who spends a large measure of income on the interest and is fascinated enough by the subject to, you know, blog about it pretty much every day and even write chapters in books about its regulation likely also considers it “fundamentally or inherently personal”. I will not digress further on this point but to note the case was not on booze and if it was on the issue relating to a lawyer’s wine cellar, the court might have had other sympathies – and the difference between wine and marijuana might well justify such a difference. Suffice it to say, however, that this is a reasonable example and description of the underlying human right as against the state that is at play when we are talking about Prohibition in this context. And, if we thing of our tropical ecological taxonomist above, the name of that right is “autonomy.” So, having established the nature of the right, we can now move on to the question of the nature of what is “prohibition”.

I am going to take a break now, go take more meds, have a nap and a think, and pick up from here later today.

Later that day: That’s better. So where were we? Yes, prohibition. So if we have a right and then we have a prohibition and then we have a repeal, where are we? Back with the right, right? But we are not. We do not live in relation to alcohol as we did before the beginning of prohibition are we. And when was that anyway? Well, if by prohibition we mean an total ban on all activity related to the trade, transportation, manufacture, possession and consumption of alcohol that never happened in Canada. The US introduced an amendment in 1919 to its constitution that imposed the following:

After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited.

Canada, by comparison, had a national referendum in 1898 under which, although 51.3% approved prohibition only 44% of the population voted according to Craig Heron at page 172 of his highly recommended book Booze which I quoted from back in March. Heron describes the difference between the US and Canada’s approach in this way:

Canada, by comparison, had a national referendum in 1898 under which, although 51.3% approved prohibition only 44% of the population voted according to Craig Heron at page 172 of his highly recommended book Booze which I quoted from back in March. Heron describes the difference between the US and Canada’s approach in this way:

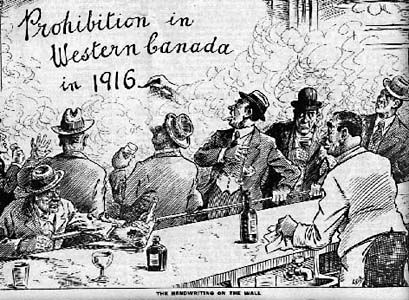

Defeat at the national level set Canada’s prohibition movement on a different course from its US counterpart. South of the border, as state prohibition experiments were failing and the Supreme Court reinforced federal powers to intervene on this issue as an aspect of federally controlled interstate commerce, prohibitionists looked to Congress for action and then, in 1913, decided to seek and anti-booze amendment to the Constitution. In contrast the Canadian movement turned decisively back to the provinces, where members would concentrate their energies for the most part of the next three decades. Canada’s highest court helped shape that strategic direction with its 1896 and 1901 declarations that prohibiting the sale of booze within the boundaries of one province was a solidly provincial responsibility.

So up here, each province charted its own course. People certainly were arrested and beer barrels put to the axe. Little PEI imposed the strictest ban in 1901 that lasted until 1948 – which triggered a continuing fine but entirely illegal moonshine trade as well as the blind pigs of bootlegging bars, a dirty open secret that was tacitly accepted right up until just a few years ago after a man died at the bar in one of these establishments…and no one noticed for a while. Other provinces took other actions over the early decades of the 1900s, none of which entirely banned personal possession and none of which was in line with the others. A patchwork was created under which alcohol was more or less available if you wanted it. There were some reasons for this.

So up here, each province charted its own course. People certainly were arrested and beer barrels put to the axe. Little PEI imposed the strictest ban in 1901 that lasted until 1948 – which triggered a continuing fine but entirely illegal moonshine trade as well as the blind pigs of bootlegging bars, a dirty open secret that was tacitly accepted right up until just a few years ago after a man died at the bar in one of these establishments…and no one noticed for a while. Other provinces took other actions over the early decades of the 1900s, none of which entirely banned personal possession and none of which was in line with the others. A patchwork was created under which alcohol was more or less available if you wanted it. There were some reasons for this.

- Canada then as now simply does not have a constitution in one document. One hundred years ago it was still subject to British Parliamentary approval for major changes which would be the equivalent of a US constitutional amendment. As a result, the approach was more local and regulatory because that was the available law.

- Quebec voted heavily against prohibition in 1898. A whopping 81.2% of the electorate voted against it. Canadian politics being what it is, any prohibition against booze had to take that into account.

- After WWI, there was a social change in Canada whereby the rights and dignity of the worker was raised in the consciousness of the land. General strikes ending in deaths of strikers placed veteran against veteran. And having had a longer war than the US, there was no doubt greater Canadian exposure to freer social drinking from 1914-1918 in Europe.

- Practices like continued access to 2.5% beer in taverns, medical prescriptions and drug store slips for medicinal alcohol and inter-provincial shipments from “wholesalers” were openly abused throughout the “prohibition” period.

There is another thing. Frankly, we Canucks were and, to be fair, still are a nation of loop hole seekers. Our relationship to the state is less fundamental in most of Canada than in America. We do not pledge allegiance to the flag so much as answer questions posed by police officers and other officials with our fingers crossed behind our backs. This national characteristic is accentuated by legal patchworks and common access to other jurisdictions where the law is different than where each of us lives.

The patchwork of rules and access to other jurisdictions continues. In a real way we never had prohibition, just degrees of regulation. Plenty of that makes sense. No one wants ten year old children standing in the liquor store line-ups and no one wants people to clean of a case of beer and then drive away from the party. There will always be regulation of some aspects of the booze trade. But there are plenty of laws that people not only flout but that officials do not enforce and sometimes do not even know exist. We are like that. Just consider that certain comic books still are prohibited under our national Criminal Code…a provision that is never enforced.

No, still today vast provincial bureaucracies exist, like Ontario’s LCBO, which impose costly regulation, which no one really cares about and which do not real describable good other than perpetuate a vision of a society in need of protection from demon rum. There is plenty of booze for all under these systems of oversight but also plenty of rules continued directly from the “prohibition” period. When I was in university, it was still illegal in PEI to stand in a bar and be holding a beer at the same time. All drinking was to be seated. Here in Ontario and elsewhere, importation is restricted on craft beer and other alcohols even though I can drive into the US and buy the stuff myself and bring it back within hours. Labels on bottles must be in line with regulations that only apply here, causing needless delay and cost. Due to lab testing and other requirements, I have a hard time saying that most beers in the LCBO system could be considered fresh – except those of small local brewers who, as I learned late last winter, control deliveries themselves like Beau’s All Natural here in eastern Ontario, as so romantically illustrated to the right.

No, still today vast provincial bureaucracies exist, like Ontario’s LCBO, which impose costly regulation, which no one really cares about and which do not real describable good other than perpetuate a vision of a society in need of protection from demon rum. There is plenty of booze for all under these systems of oversight but also plenty of rules continued directly from the “prohibition” period. When I was in university, it was still illegal in PEI to stand in a bar and be holding a beer at the same time. All drinking was to be seated. Here in Ontario and elsewhere, importation is restricted on craft beer and other alcohols even though I can drive into the US and buy the stuff myself and bring it back within hours. Labels on bottles must be in line with regulations that only apply here, causing needless delay and cost. Due to lab testing and other requirements, I have a hard time saying that most beers in the LCBO system could be considered fresh – except those of small local brewers who, as I learned late last winter, control deliveries themselves like Beau’s All Natural here in eastern Ontario, as so romantically illustrated to the right.

As a result, I also have a hard time saying that repeal means anything to me because there has never been a repeal of the program of regulation that was imposed during the period of regulation. I can’t buy a beer in a corner store in Ontario – though I can drive two hours to Quebec or an hour into New York state if I want to. I cannot buy a beer here which is not inflated in price due to taxation, minimum pricing rules, duties and state monopolistic practices. So in answer to the questions above, repeal means nothing as it never really happened and to celebrate my right to drink beer, I will drink the beer that I am allowed to have by my bureaucratic betters. Whoop-dee-doo.

[Original comments…]

Jeff of Stonch’s Beer Blog – December 5, 2008 4:37 pm

http://stonch.blogspot.com

Alan, regarding your first paragraph – well said. I dropped out of the Session a while ago because I felt the topics chosen were more often than not hopeless. When it was my turn, I could have very easily choose a topic that was only relevant to the UK. I didn’t. Why was a commercial website allowed to head this up?

The Beer Nut – December 8, 2008 10:33 am

http://thebeernut.blogspot.com

Have to say: I think banning drinking standing up is quite a good idea. It’s a condition of restaurant licences here, and when the aborted attempt to liberalise pub licensing happened a few years ago, the proposed “café bars” would also have required customers to be seated to be served.

Bar owners, in central Dublin especially, have a tendency to see their establishments as something close to a high-density feed lot.

Jeff of Stonch’s Beer Blog – December 8, 2008 5:45 pm

http://stonch.blogspot.com

Beer Nut, your comment leaves me speechless. Do you actually like pubs?

The Beer Nut – December 8, 2008 6:55 pm

http://thebeernut.blogspot.com

If they’re comfortable and serve good beer then I love them. But applying these two criteria to pubs where I live means the answer is no, not really. I’d rather drink something decent, at home, where I can have a conversation at the same time. Pubs don’t offer me that.