Before the curse that is social media was thrust upon us, one key promise of beer blogging was collective research. With the most welcome news that Lew is back into the beer blog game, he reminds us of the point of doing this day after day:

A bit over two years ago, I stopped writing this blog. It wasn’t because blogs are dead — I refuse to believe that — and it wasn’t because I got bored, and it certainly wasn’t because I was running out of things to say. Blogs, good blogs, relevant blogs still are vital, and they don’t have to be on Tumblr, or run through a microplane grater and splattered onto Twitter, or covered in kitties and posted on Facebook. Blogs are the place to do long-form writing, and I like to think I was able to balance somewhere between a tweet and tl;dr.

Even though I shared in the publication of two histories the year before, 2015 was the year I think I took my interest in brewing history most seriously. That few care about the state of brewing and porter selling in New York City in the decades around the Revolution is no concern of mine. It’s important just to write about it. Same with the centuries of brewing on Golden Lane and life in London, England’s district St. Giles’s Cripplegate. These things are interesting because they are true.

We are children of the Enlightenment. Three things we depend on for understanding were all invented and popularized in the 1700s: the application of science in practical matters, mass communications and commercial branding of products. Each is a means to create a lasting record, each a self-archiving activity. People are led to believe, as a result, that things prior to the advent of these phenomena were unlike today. No scientific brewing? No pale ale. No newspaper? No news. Folk actually believe these things. They believe folk didn’t know how to make fine things with available resources. We are slaves to records. We need to distrust them more even as we dive more deeply into them. Which leads us today’s new topic: Northdown ale. Never noticed the stuff until Jay tweeted this quotation from Pepys yesterday. Which got me looking for more information and found an excellent blog post from November 2014 posted on the excellently titled blog Things turned up by Sally Jeffery while looking for something else as well as this passage from a travel guide called All About Margate and Herne Bay reviewed an 1865 magazine named The Athenaeum:

Quoting largely from the Rev. John Lewis’s account of Margate, written in 1723, he notices the once famous beverage, known to Charles the Second’s thirsty subjects by the names of “Northdown Ale” and “Margate Ale” of which drink Lewis says, “About forty years ago, one Prince of this place drove a great trade here in brewing a particular sort of ale, which, from its being brewed at a place called Northdown in this parish, went by the name of Northdown Ale, and afterwards was called Margate Ale. But whether it’s owing to the art of brewing this liquor dying with the inventor of it, or the humour of the people altering to the liking the pale north-country ale better, the present brewers send little or none of what they call by the name of Margate ale, which is a great disadvantage to their trade.” This was the beer which Evelyn calls “a certain heady ale ” ; and it is probable that its popularity with London beer-drinkers influenced the generation of brewers who fixed the immutable properties of “stout.”

So, an 1865 citation of an account from 1723 recalling a drinking experience from forty years before that. Northdown Ale. In her blog post, Ms. Jeffery surveys the evidence and seeks to determine if she can “get a better idea of what the ale was like by looking at how it was made.” Let’s now see if we can add anything. First, I like the reference to Herrick. In one edition of his book, there is a footnote to another poet’s* line of verse anthologized in 1661: “For mornings draught your north-down ale / Will make you oylely as a Whale.” Pepys was drinking Northdown ale the year before. I am not sure why one might want to be so oily. Franklin referenced “he’s oil’d” in his 1730’s Drinker’s Dictionary. I am going to assume it means the beer is staggeringly strong for the moment. In The Curiosities of Ale & Beer: An Entertaining History from 1889, Herrick’s own lines on Northdown Ale from “A Hymne to the Lares”¹ are quoted:

The neighbouring county of Hereford, now a great cider-drinking locality, had in former times at least one town with a reputation for good ale. “Lemster bread and Weobley ale” had passed into a proverb before the seventeenth century. The saying seems, however, to have been affected chiefly by the inhabitants of the county, who, perhaps, were not quite impartial. Ray, writing in 1737, ventures to question the pre-eminence ascribed to the places mentioned. For wheat he gives Hesten, in Middlesex, “and for ale Derby town, and Northdown in the Isle of Thanet, Hull in Yorkshire, and Sandbich² in Cheshire, will scarcely give place to Weobley.” Herrick mentions this celebrated Northdown ale in the lines:—

That while the wassaile bowle here

With North-down ale doth troule² here,

No sillable doth fall here,

To marre the mirth at all here.

Did you see that? Wheat. Is this strong wheat ale? Or is that just a juxtaposition of two products of the region? Not sure. Likely the latter, given Jeffery’s references to an excellent but short lived barley malting trade concurrent with the height of Northdown ale’s prominence. Also, the diarist, botanist and courtier to Charles II John Evelyn describes being in Margate, one mile west of Northdown, on 19 May 1672 and states:

Went to Margate; and, the following day. was carried to see a gallant widow, brought up a farmeress, and I think of gigantic race, rich, comely, and exceedingly industrious. She put me in mind of Deborah and Abigail, her house was so plentifully stored with all manner of country provisions, all of her own growth, and all her conveniences so substantial, neat, and well understood; she herself so jolly and hospitable; and her land so trim and rarely husbanded, that it struck me with admiration at her economy. This town much consists of brewers of a certain heady ale, and they deal much in malt, etc. For the rest, it is raggedly built, and has an ill haven, with a small fort of little concernment, nor is the island well disciplined ; but as to the husbandry and rural part, far exceeding any part of England for the accurate culture of their ground, in which they exceed, even to curiosity and emulation.

Which tells us there were many brewers and much malting in a rich farming district. And notice another thing from the quoted text further up. Thanet. Which reminds us to ask the particular question – where exactly is Northdown? That image above is from this map from 1711. If you click here you will see a supremely confusing cross-referencing of the 1711 map with a 1623 image on Jeffery’s post. See, before branding, newspapers and scientific brewing you needed to know where a beer or ale was from to figure out what to expect. Northdown is located in southeast England in the county of Kent – as in land of the noted hops. But the land of hops most noted about 200 years after Herrick wrote his lines. It was, also, the site of the October 2015 drinking session of the year as recorded by Team Stonch. So in the 1600s, the 1800s and the twenty-first century, a place of good beer but in each era quite distinct good beers.

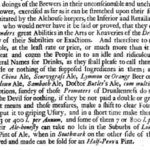

Click on that image to the right. It’s a paragraph from a 1681 treatise entitled Ursa major & minor: or, A sober and impartial enquiry into those pretended fears and jealousies of popery and arbitrary power, in a letter. Clearly an unhappy guy. But what he’s unhappy about is how, in tough economic times, brewers are making undue profits by not only jacking up prices but doing so by having “devised several name” for drinks including China ale, Hull ale – and Northdown ale. Sound familiar? Double the price for poorer beer? And you thought craft beer invented that trick. It appears to have been quite popular with the well placed in addition to the poets. John Donne – the Younger³ – recounts being sent a poem along with “a dosen bottles of Northdown ale and sack” which means it was good enough to bottle and, seeing as it was sent by Lord Lumley, good enough for the Peerage. Which might explain the jacked up price. A premium ale for those that can afford it.

Click on that image to the right. It’s a paragraph from a 1681 treatise entitled Ursa major & minor: or, A sober and impartial enquiry into those pretended fears and jealousies of popery and arbitrary power, in a letter. Clearly an unhappy guy. But what he’s unhappy about is how, in tough economic times, brewers are making undue profits by not only jacking up prices but doing so by having “devised several name” for drinks including China ale, Hull ale – and Northdown ale. Sound familiar? Double the price for poorer beer? And you thought craft beer invented that trick. It appears to have been quite popular with the well placed in addition to the poets. John Donne – the Younger³ – recounts being sent a poem along with “a dosen bottles of Northdown ale and sack” which means it was good enough to bottle and, seeing as it was sent by Lord Lumley, good enough for the Peerage. Which might explain the jacked up price. A premium ale for those that can afford it.

Notice one more thing. Sally Jeffery suggests there was indication that the ale was dark but also sees that “[t]he wheat stubble that is left is either mown for the use of the Malt-men to dry their Malt…” which, as we know, would make the sweetest, palest malt during that era. Enough to confirm anything? Nope. All we see from this set of records is clearly (i) a premium product, (ii) defined quite clearly to a time and place which was (iii) notably strong and (iv) bottled. The best ale during the Restoration? Maybe.

*Likely this John Phillips, royalist lad and nephew of Milton.

¹Here is the whole text of the poem:

It was, and still my care is,

To worship ye, the Lares,

With crowns of greenest parsley.

And garlick chives not scarcely:

For favours here to warme me,

And not by fire to harme me;

For gladding so my hearth here,

With inoffensive mirth here;

That while the wassaile bowle here

With North-down ale doth troule here,

No sillable doth fall here,

To marre the mirth at all here.

For which, o chimney-keepers!

(I dare not call ye sweepers)

So long as I am able

To keep a countrey-table,

Great be my fare, or small cheere,

I’le eat and drink up all here.

²I understand Sandbich to be “Sandbach” and troule means to “pass about.”

³“…an atheistical buffoon, a banterer, and a person of over free thoughts…”

[Original comments…]

Alan – January 2, 2016 4:24 PM

Lots more here.

Alan – January 7, 2016 4:41 PM

A little more here too.

David Hannaford – January 10, 2016 6:57 PM

Great article! Being a local Thanet lad (and keen beer drinker) I’ve done some research into Northdown Ale, having been fascinated by Pepys’ entries in the diary. The “one —– Prince of this Place” in the Lewis book was John Prince, listed as a brewer in the local parish register at his death in 1687. But he was only 33 at his death, and his brewery and land was at that time in Margate in what is now Mill Lane near St John’s church. The Lewis quote (the book written only a generation or two after John’s death) actually says it was called Northdown Ale from it FIRST being brewed there (the Thanet hidden histories blog shows photos of what’s believed to be the original brewery and well) and afterwards Margate ale- the brewery obviously moved, maybe to be nearer the port, and must have been a dynasty as John was only 7 or so when Pepys mentions the brew in 1660. Pepys drinks it on board ship, the Naseby (the “coach” in the diary is a cabin), on its way to collect Charles II for the restoration of the monarchy. It’s quite possible the ale was supplied to the navy, for ships in the downs, though the strong stuff Pepys drank would be for officers only presumably, and not the beer which the average sailor would have received as part of his rations..

As to what the ale was like we can only guess. Glass being so expensive it would probably not have been bottled at the brewery, most likely sent out in casks of various sizes then bottled for private use, or sending out as gifts to friends, in quart bottles.

Correspondence with the beer writer, Martyn Cornell, led him to surmise it was probably 8% abv or maybe stronger (Pepys gets someone almost drunk on a bottle, ie 2 pints), lightly hopped (ale and beer being taxed and regarded as almost different drinks then, beer being generally weaker but more highly hopped), amber to brown, it being too early for pale malt to be

used (in these parts anyway – Lewis mentions the “humour of the gentry and people altering to the liking the pale north country ale better” so pale malt was beginning to be produced, if not in Kent in the 1680s).

Whatever, it was for a large part of the 17th century a nationally famous, renowned and quality brew, something us Thanet ale drinkers should be proud of. John Prince sired several children: sadly, all, l as far as I can tell, died young. He left at least one brother, a mariner, but nobody took up his brewery. There were other brewers in the town, and another more famous brewing dynasty, Cobb, took up in the following century, but as Lewis said “the art of brewing this liquor.. (died ).. with the inventor of it .. . .

David Hannaford – January 10, 2016 7:47 PM

I should have written that the Thanet hidden history blog has published photos of what the blogger believes to be the site of the original Northdown brewery and well, in a cottage in East Northdown. Very exciting, and quite possible, the well looks big for ordinary domestic use, and it had to be there somewhere. Another claimed site is in Holly Lane, West Northdown. John Prince’s father was William Prince, I assume he was the brewer of the original Northdown Ale enjoyed by Herrick and Pepys. Did his father brew before him? Alas, all lost in the mists of time. Thanet was renowned for its barley, but how would a ‘common brewer’ have started up in a small parish at the edge of Kent in the mid 1600s and become so famous? Quite intriguing.

Alan – January 10, 2016 9:35 PM

That is great! Thanks for all that information. Note one thing. There is a bit of a myth about no pale malt before mid-1650s coke drying of malt. Not sure that the end of Northdown in the 1690s can be caused by Burton either given the Trent is not improved to allow export until 1712.

I have no connection to Thanet at all, by the way. Just fascinated by the history.

David Hannaford – January 11, 2016 10:45 AM

Thanks for your interest and input, Alan, and for the info about pale malt. I’ve been fascinated by the Northdown Ale thing for years now. It was thrilling to find “John Prince, brewer”, in the transcripts of the parish registers in St John’s church in Margate, and know he was buried in the church or graveyard somewhere, sadly with an infant daughter who died a few months later (a “Tour through the Isle of Thanet” in 1793 lists a stone with their names, ages and and date of death in the church, but I can find no trace of this now).

I have a copy of his will:he appears to have been quite wealthy, and at least at the time of his death he had 3 surviving children, but all very young as he was only 33 himself and had only married 8 years earlier. His date of death fits in exactly with Lewis’ “about 40 years ago..” But he left his “dwelling house, brewhouse, mill house and outhouses . .at a place called Church Hill in Margate” (This is what is now Mill Lane, very near the church). He also owned land and other property in Margate and St Peter’s, but there’s no mention of Northdown, frustratingly. A seperate inventory of the brewery is fascinating, too, this is what mentions the “hopp house”.

John’s father, William, was born in 1617. I’m assuming he was the original brewer at Northdown who came up with the ale in the first place (John being only 7 when Pepys mentions the ale in 1660), but can find nothing to prove this. What I could do with is tracking down some naval victualling records, or contracts linking father or son to supplying the navy…

But as to why the ale died with him? Possibly simply that there was nobody to take the brewery on, his children being so young, and other brewers in town to take up the trade. Had John lived another 20 or 30 years, and his sons also survived long enough to learn the trade, maybe the brewery would have continued and flourished for centuries to come? Fascinating to conjecture.

Alan – January 11, 2016 8:25 PM

Here’s my question. What if it’s not so much that the ale ceases to exist so much as Northdown ceases to have a separate identity from Margate? Interesting that he was so wealthy, too. Makes one wonder about the timing of the rise of commercial brewing but, as you suggest, having the ship trade to service out of Margate may have been the trigger. I was reading in Unger that Hamburg had a massive brewing trade for bothe the ship trade and export as early as the 1300s. Why on one side of the North Sea and not the other?

David Hannaford – January 12, 2016 5:44 PM

That’s a moot point. Pepys seems to regard Northdown and Margate ale as the same thing. My assumption that both were produced by the same family, the Princes, rests only on Lewis’ observation, but he was writing well within living memory. There were certainly other brewers in town, whose beer could presumably also be sold as Margate Ale without infringing any trade descriptions act or copyright! Evelyn confusingly says the town much consists of brewers (plural) of a certain heady ale. Does he mean more than one brewer was producing a version of famous strong ale? Northdown is roughly a mile and half to 2 miles from Margate old town – all swallowed up into Margate by the 20th century, but in Stuart times a distinctive, and much smaller, settlement, separated by farmland and fields and reached by a rough road and footpaths. I can’t see any reason for an ale brewed in Margate to be called Northdown Ale, unless an early advertising agency decided it sounded more rustic and appealing! But again, Lewis, a pretty diligent historian as far as I can tell, refers to the ales as one and the same, and you’d think fairly conclusively, says it was formerly Northdown Ale from it first being brewed there.

As to your second point. Margate had a reasonably sheltered harbour, and a system of ‘droits’ or taxes, for the its upkeep. Lewis again – I’ll sum up – ships from Margate, trading within his majesty’s dominions, burden of 40 tons or upward, paid 2 shillings (lesser burden 1s 4d). That could include a lot of beer for London? They bothered to charge higher rates for exporting to the Netherlands (Margate reckoned to be the shortest passage there), France, Spain, the East Country (India??) and “Southward”, for “great vessels”. (Interesting to also note beer and ale must have been imported too as there’s a tax on unloading both – listed seperately, 1s for a barrel of beer and 2s for a barrel of ale, surely an indication that they were viewed as different drinks and different strengths?)

John Prince’s inventory at his death includes a mash tun and 3 small ale tuns,

2 hogsheads, 105 small ale casks, and 19 herring “barrells” (why? storing for fishermen friends/family, or could they be new ones adapted for beer?) in the brewhouse. In the cellar are 22 hogsheads, 121 herring barrells ,and 25 small beer casks. Oh, and no bottles. It values the items in the cellar at £19 4s 10d. I’m not sure if that means they’re all full, I assume the cellar would be for storing beer rather than empty barrels, or what size was the brewery and what its output was? 22 hogsheads of 52 gallons? Not a huge amount for a common brewer? The population of Margate, 40 years later, Lewis reckoned at 2,400, and Thanet as a whole 8,800, by the way.

Thanet CAMRA have a heritage and Asset of Community Value sub committee who want to

a) produce a 2018 calendar which will include old beds and hostelries of Thanet

b) A publication of Margate pubs and breweries.

It would be great if we could get your input acknowledgements all round of course. Please feel free to email me.

Interesting that passing mention to Sandbach (“Sandbich”, also “Sambach” in other sources, the second syllable is pronounced “batch”). Its beer seems to have become known in the mid-17th century, and was compared favourably to the “nappy beer of Derby”. I wonder if its rise is something to do with the dislocations of the Civil War – Derby was staunchly Parliamentarian so may have had problems physically getting beer out, whereas Cheshire was more..ambiguous. Another factor is that the late 17th century got really cold, in fact there has not been a colder winter than 1683/4 in the last 350 years. Derby’s not warm at the best of times….

Sandbach beer seems to have petered out in the 18th century – presumably because it was less favourably placed for transport than Burton by that stage. There’s no tradition of brewing there now, although most of Cheshire has really nice soft water.

Yes, Burton and porter appear to bully out these regional / city named beers in the second quarter of the 1700s. Both were innovations but I am not sure what the particular change was. Novelty? Must be more than that. Margate lasts into the first half of the 1800s. Working on a big post at the moment trying to get my head around it all.