That passage above is from the The Voyage Made by M. John Hawkins Esquire, 1565. According to the wisdom of Wikipedia, Hawkins was the chief architect of the Elizabethan navy, the first English trader to profit from the Triangle Trade, proudly inhuman slaver and Treasurer of the Navy from 1577 to 1595. Its from a part of his journal that records French colonial efforts in Florida at their short lived Fort Caroline. While the colony had only been settled in 1564, they had already turned local grapes into wine, apparently the first in North America.

That passage above is from the The Voyage Made by M. John Hawkins Esquire, 1565. According to the wisdom of Wikipedia, Hawkins was the chief architect of the Elizabethan navy, the first English trader to profit from the Triangle Trade, proudly inhuman slaver and Treasurer of the Navy from 1577 to 1595. Its from a part of his journal that records French colonial efforts in Florida at their short lived Fort Caroline. While the colony had only been settled in 1564, they had already turned local grapes into wine, apparently the first in North America.

It’s not the earliest record of alcohol use in North America – even if it might be the earliest of production. We have seen before how the French were drinking cider as they worked the Newfoundland shore in the 1520s. But what is interesting to me is that the French in Florida had their choice of products, given the ample source of good bread making grain, but made wine. Which is reasonable as wine is simpler to make than beer, given there is no intermediary stages like malting or mashing.

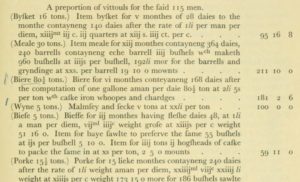

A few years ago now, I discussed the provisioning of Martyn Frobisher’s 1578 voyage to mine iron ore on Baffin Island in Canada’s Arctic. The post was based on my luck find of the victualing records. Have a look by clicking on the image to the right. You can see how much biscuit, meal, beer, wine and pork was loaded on board. Note: beer, not malt. He was not brewing beer up on Baffin that year. I’ve discussed late 1500s trans-Atlantic ships’ provisions of malt before, too.

A few years ago now, I discussed the provisioning of Martyn Frobisher’s 1578 voyage to mine iron ore on Baffin Island in Canada’s Arctic. The post was based on my luck find of the victualing records. Have a look by clicking on the image to the right. You can see how much biscuit, meal, beer, wine and pork was loaded on board. Note: beer, not malt. He was not brewing beer up on Baffin that year. I’ve discussed late 1500s trans-Atlantic ships’ provisions of malt before, too.

I have been a bit fruitlessly looking for more of those sorts of records, feeling a bit like Manilov in Dead Souls, not getting very deep into things. I want to turn the clock back further, back past Cartier in the mid-1530s. I have been primarily thinking about what was down in the hold of John Cabot‘s ships on his 1490s voyages to eastern Canada. Until I got into the Cabot era, I had no idea how lucky I was finding the record for Frobisher. An actual victualing bill from the 1570s. Lucky also that the scholarship on that adventurer was not as quirky and proprietary as was the case (perhaps until recently) with Cabot. That has recently broken somewhat in recent years. In 2012, The New York Times reported:

In 2010, an international team of scholars working together in what is called the Cabot Project came upon a set of 514-year-old Italian ledgers that Dr. Ruddock had found decades earlier but which had disappeared from view. They showed that in the spring of 1496, Cabot received seed money for his voyages from the London branch of a Florentine banking house called the Bardi.

Plenty has come out related to the new Cabot findings that has given me a bit more hope. We know that Henry the VII gave notice in 1496 that Cabot was authorized to buy victuals for his first voyage and also authorized the second voyage in 1498. We also know that in 1499, a Bristol merchant named William Weston sailed to Newfoundland.* Cabot also might have settled friars at Carbonear, Newfoundland on his third voyage. But there is that problem of the vulnerability of scholarship… ie, people who I can poach from. That hoarders of ideas Cabot scholar Ruddock died in 2005 and Peter Pope who wrote wonderfully about the early Newfoundland trade died in 2017. So I am left to my own wits.

Which means I have to come up with rules for my own research. What do we know? Well, we do know that Bristol was the gateway for English expeditions to the west just as London and other eastern facing ports served, generally speaking, the North and Baltic Seas. In particular, Bristol had a flourishing wine trade in the 1400s. The quantities involved were significant – between 1,000 and 2,500 tons of wine a year through the 1400s, depending on the politics. We have to recall that the English held Gascony from the 1200s until the 1450s. Gascony is know for wine, even including the Bordeaux region. Bristol was where that wine was received for English consumption. So, it is reasonable to expect provisioning of vessels leaving Bristol in the 1400s to have a supply of wine.

Additionally, to find trans-Atlantic provisioning records you need to find trans-Atlantic voyages. Where were the merchant adventurers of Bristol during the English Renaissance sailing towards? First, we have to remember that the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance ratified at the Treaty of Windsor in 1386 is arguably the oldest alliance in the world. The Portuguese were also makers of wine for the English market as well as explorers. And that wine landed at Bristol. So they were sailing back and forth from there. Voyages, trade links and colonization out into the Atlantic was not a particularly wide-spread European habit before the 1400s. The Canary Islands, populated by a semi-Stone Age people, the Guanches, were only taken by Spain in 1402. Yet trade links with Iceland were developed by Bristol’s merchants by the mid-1400s which included a:

diversity in food [which] increased as the English… imported large quantities of beer and wine, salt and pepper, malt, wheat, sugar and honey.

Which means if the Bristol merchants are shipping beer to Iceland… there is beer on Bristol ships heading north. And, fabulously, malt. And other targets for the adventurous traders of Bristol were developed like the voyage of the Trinity in 1480-81 seeking out opportunity in North Africa. Was there beer in that hull, too? It’s not unreasonable to think so. We do know that the well-armed naval merchants of the Baltic-based Hanseatic League did not themselves get out into the Atlantic but they did bring hopped beer to England as early as the mid-1200s. Remember the cargo of beer brought on the Elyn of 1401. Which means that you have the conditions to have hopped beer moving out of England, too, as a transferred on trade good. Quite a bit early than I had thought.

I will illustrate my working date with some fairly common understanding of dates. Professor Unger identified “about 1520” as the time when the English mastered the new technology of brewing beer with hops. That is backed up by the records showing written references to “hops” or “hoppes” were not so common until about that same time. Yet, if you dig around the records a bit, that date starts to look a bit late. In records (“alien subsidies”) of foreign merchants for Bristol in the mid-1400s we read that:

…the returns to the 1449 and 1453 alien subsidies, which in some cases give either occupational descriptions or surnames that suggest an occupation: there are two beer-brewers, two tailors, a pinner, pointmaker (maker of laces for securing clothing), shearman, bellmaker, leatherworker, goldsmith, smith and, possibly, heardsman…

Which means that there were two immigrant beer brewers in Bristol well before Cabot and about the time of the Icelandic trade. Which means the beer heading north could well have been English beer and even made close to the port. Further, in the 2014 PhD dissertation by John R. Krenzke of Loyola University in Chicago, “Change Is Brewing: The Industrialization of the London Beer-Brewing Trade, 1400-1750” we read, at page 42, that a similar timeline is at play in London:

Ale brewers were successful in 1484 in having the City of London lay down the ingredients that could be used in ale brewing—“only liquor (heated water), malt, and yeast”—to limit the competition that ale brewers faced from beer brewers. In response the beer brewers of London were able to obtain a charter to become their own guild in 1493. The two groups were to remain apart and in direct competition to each other until 1556 when they were merged.

The “stranger” beer brewers were allowed to sell beer freely in London in 1477 and were not as unwelcome at all as we read on page 7:

…at first, beer remained primarily a beverage brewed by foreigners, known as strangers to their English hosts, for themselves and, because of its stability, for English soldiers. Stranger beer brewers found the Crown to be an ally throughout the fifteenth century because of their ability to supply beer to the military.

Nothing like government demand to validate new technology. And we need to recall in all this that Henry VIII himself created great state-owned naval brewing capacity at Portsmouth in 1515, producing 500 barrels per day to supply his military ambitions. Just before Unger’s date of 1520. The question, then, is how large the capacity of the privately operating beer brewers of Bristol was half a century earlier and did it supply the merchant adventurer ships heading west to Canada in the 1490s. That is the question I need to dig at. All the conditions are present: confident merchant adventurers, established beer brewing and thirst. All we need is a record or two.

*Much more here on the scale of the oceanic Bristol trade missions in “The Men of Bristol and the Atlantic Discovery Voyages of the Fifteenth and Early Sixteenth Centuries,” the MA Thesis of Annabel Peacock from 2007.