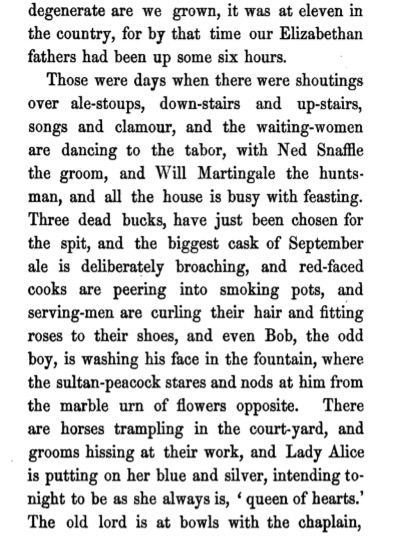

It all got messy mid-week. It was looking dull and then a number of big things happened. More about those things later. The best thing, a littler thing, is not really one of note – it’s that Ron wrote a few travel posts as he wandered about England as a Goose Island consultant. Not that I mind his recipes and quotations from rulings of the magistrate’s court circa 1912 but his real gift is capturing the normal life of a guy and his problem with beer. Consider the gorgeous photo he attached to one post which I have pilfered and plunked right there. I have dubbed it “Ronnui“: lovely wood and glass inside with unloveliness outside and across the road. And a man considering the emptiness of it all. You sense that even the umbrella he brought won’t be enough. A fire extinguisher serves as a warning to you. Not the sort of thing you’ll see in one of the new dipso guides to global vagrancy. Editors don’t like that sort of detail. No, this is honest stuff. Click on the image, look upon Ron’s work and despair.

It all got messy mid-week. It was looking dull and then a number of big things happened. More about those things later. The best thing, a littler thing, is not really one of note – it’s that Ron wrote a few travel posts as he wandered about England as a Goose Island consultant. Not that I mind his recipes and quotations from rulings of the magistrate’s court circa 1912 but his real gift is capturing the normal life of a guy and his problem with beer. Consider the gorgeous photo he attached to one post which I have pilfered and plunked right there. I have dubbed it “Ronnui“: lovely wood and glass inside with unloveliness outside and across the road. And a man considering the emptiness of it all. You sense that even the umbrella he brought won’t be enough. A fire extinguisher serves as a warning to you. Not the sort of thing you’ll see in one of the new dipso guides to global vagrancy. Editors don’t like that sort of detail. No, this is honest stuff. Click on the image, look upon Ron’s work and despair.

US big picture: 4,900,000 fewer barrels of beer were made in 2017 compared to 2016.* A retraction of a little more than 2.5% and twice the drop for 2015. What you will hear about will include how 30,000** more barrels were consumed at brewery taprooms. That represents 0.6% of the total loss of overall production. Pick your top trends accordingly.

More big brainy stuff. I found a 2008 MA thesis on beer and tourism in Yorkshire. I found it as part of finding out more about York Brewery (1996-present) whose necktie I just added to the old man office wear collection. So not really really big stuff – but it is a 62 inch tie so that is good.

Biggish? In just two weeks two glossy quarterly Ontario-centric beer mags have been announced. Overlapping writers. Won’t last. Can’t last. Who will blink? Or will they both starve the other enough that each folds?

Pretty big. Dave Bailey announced the closure of hi brewery, the much-loved Hardknot (2006-1018). I was not shocked but certainly saddened. I was one of those who this time last year was muttering at a laptop screen saying “don’t!… DON’T sell your house to save your business!” even though I was rooting for him and his family. While others missed the point entirely, Mark Johnson gathers together a fabulous remembrance of when, among other things, Hardknot was as big as BrewDog when both were small. Big news that:

Of all the comrades that e’er I had

They’re sorry for my going away

And all the sweethearts that e’er I had

They’d wish me one more day to stay.

But since it fell unto my lot

That I should rise and you should not

I gently rise and softly call

Good night and joy be to you all.

Then? Good to see he is already planning his next phase, Guerrilla Brewing.

Big but not big. One thought that the ascendancy of “juicy” or “hazy” to the preference of “NEIPA” or, the most honest, “London murk” was as big a day as when almost everyone got to join the US small craft brewers. What next, adding makeup sparkles? As if that would happen!

Conversely, the best thing of the week is this 1975 news item on the making of Traquair Ale. Plainness and excellence.

And one last thing… hmm… how about this. Is this you?

Recovered beer snobs, also known as “geeks” or “nerds,” are generally Gen Xers who’ve spent years swirling and sniffing taster-sized samples, waiting in line for Heady Topper, and posting pictures of their beer hauls. They’ve gone through a lupulin threshold shift that carried them from IPAs to 100-IBU imperial IPAs, and then on to sours because their palates had basically grown numb to anything that didn’t blow it to pieces. But, as observers predicted, they eventually got tired. They overloaded. They grew up. And they stopped wanting to think so hard about beer.

“They grew up“! Fabulous. And not without some basis. Lisa noted that we are on the top of the craft beer cycle wheel again. Andy is noting the return to lite. I get it. I am not much interested in anything too strong and certainly nothing too cloudy, fruited or hopped. Did I grow up? Did you? Did Lew? No, not you…Lew! We all know you didn’t. He’s in the story bearing witness: “glassware is such a first-world problem.” Boom.

*my typo as to date fixed.

**See snark in the comments. I added links to BA and TTB documents that explain. The 30,000 figure is actually for unsold beer consumed in the brewery – staff drinking, spillage and samples? The increase in taproom sales (for both craft and macro) is 385,000 barrels or so. Or 7.85% of the overall gross retraction. But they are two separate sorts of numbers. The larger one is a retraction, the other a shift in format. Context: gin and whisky are up.