I like my non-job here at A Good Beer Blog. One thing I get to do – other than never have a second beer of the same type – is meet interesting people involved with beer over the internet. Consider this exchange about beer and language between me and beer book author Pete Brown:

I like my non-job here at A Good Beer Blog. One thing I get to do – other than never have a second beer of the same type – is meet interesting people involved with beer over the internet. Consider this exchange about beer and language between me and beer book author Pete Brown:

Pete: Hi Alan, What’s a dink?

Alan: Hmm. A dink? A dink is a minor league jerk. A child’s word for penis. Actually it has a beer angle as in the Nova Scotia of my youth a six-pack was called “a dink pack” now that I think if it. A dink is a bore who is also a newbie.

Wow. Gripping linguistic drama. More to the point was the more thoughful exchange Pete provided to questions put to him by both me and guest writer Knut of Norway. Pete (no relation to the lead singer of the illustrated Pete Brown and his Battered Ornaments) has recently published a great book on his global beer travels called Three Sheets to the Wind and Knut and I thought it would be great if we could have a few questions answered in a three-way North Atlantic quiz as part of our review of his new work. You will recall I reviewed his last beer book Man Walks Into A Pub back in July 2003. In that book Pete considered some of the trends and brewing history of Britain. In this year’s book, he takes a stab at getting a hold of the global beer culture. I will review the book separately in a few days but for now, here is the interview.

+++++

Alan: You speak quite strongly about CAMRA. We do not have an equivalent in Canada though there are outposts. In “Three Sheets to the Wind” you visit Portland Oregon and experienced an expression of the North American real ale culture and appeared to love it. How would you compare the two?

Pete: I was so surprised by the US approach to craft beer – they’re really passionate about it, and the key thing is they want you to be passionate about it as well. The thing I always say about Portland is that if I was talking to a brewer about his beers and how much I liked them, he’d tell me six other beers from “competitive” brewers that I should also try. When I go to CAMRA events, I always get the sense that if you don’t already know what you like, there’s very little effort made to draw you in and help you. This is starting to change now, but there’s still an attitude about “I know more than you.” In North America, it’s more like, “I want you to know as much as me.”

Knut: Do you think CAMRA still could be used as a platform to fight for good beer, or have they painted themselves too much into a corner? Could an alternative be to start anew, based on a support for new and coming micro breweries instead of focusing on the techicalities of brewing?

Pete: Of the two alternatives, the one I’d like to see is that CAMRA reform themselves. They’ve got a terrible image problem, but they have so much stock in terms of public awareness, I still think they’re very powerful. As I’ve hung around the beer scene longer I’ve got to know more people. There are a great many executives within CAMRA who have exactly the right ideas, who know they need to reform in order to move forward – and they’re really nice people. But policy is dictated by committee and volunteers, and a lot of these guys are just professional activists – it’s not enough to be for something, you also have to be against something. I believe a lot of these guys couldn’t give a shit about getting more people into great-tasting beer; they simply enjoy the process of arguing about technicalities and being pissed off for a living. I’d like to believe the more sensible factions will eventually win the day, and we’re seeing some signs of CAMRA taking steps into the twenty first century, but there’s still a long way to go. The biggest problem is that CAMRA hardliners interpret any criticism of CAMRA as a criticism of cask ale, which is not only wrong, it’s breathtakingly arrogant, and kind of stops any really useful constructive debate from emerging.

Knut: After travelling the world, where do you see the best potential for beer tourism? I know Ireland has managed to do this based on one beer (!), and you have the mass hordes descending on Munich. But how about bicycling holidays in Bamberg and Denmark, micro breweries offering bed, breakfast and rare cask ales etc?

Pete: I’d love to see that in loads of countries. What I’m discovering now is that you can stick a pin in a map, and there’ll be interesting, often new, breweries not very far away. But I think in terms of holidays, you’d start with Belgium. I’ve been back a few times now since I went there for Three Sheets, and you can go from village to village, each with its own brewery, trying amazing beers, and it’s beautiful country – at least when the sun is shining!

Knut: Carlsberg is responding to the challenge of craft beers by a) trying to control the Danish import market and b) by setting up a micro of their own, putting a lot of prestige in it and linking it up with their brewery tours. Is this the way to go for the other big European brewers?

Pete: I think so. Big corporations in any market tend to play to the lowest common denominator with consumer tastes. You forget that to get a job as a brewer in a really big brewery, you have to be at the top of your game – the people who brew Budweiser are some of the best brewers in the world! What Carlsberg have done is give their brewers a bit of creative freedom and – surprise surprise – people can’t get enough of it. In the US, Anheuser Busch are responding to the growth of craft beers by launching some of their own, and much as I hate to say it, some of them are very good – they would be. The only thing that worries me is when big corporations react by simply trying to strangle interesting small breweries, denying them distribution and so on. This is very idealistic of me, but I wish brewers would simply let their beer do the talking – produce the best beer you can and try to sell more than your smaller competitors without resorting to dirty, underhand tactics.

Alan: I have been trying to figure out how you would approach Canadian beer culture. For me, so much about beer is centered on the kitchen party, the garage fridge or the cottage/camp as opposed to the pub or bar. In his book “Travels with Barley”, Ken Wells notes that bar bought beer in the US has gone from 75% of all sales to 25% over the last 20 years. This is a startling figure. Do you see this as a global trend? Do you also see that these sorts of home-based drinking is something that you ought to include if you extend you study to a “Son of Three Sheets to the Wind”?

Pete: That would be a great idea! An excuse to go and do the whole trip again. What we see now across the world is a consistent set of trends in markets that are “mature”, where beer has been around for ages, and a different pattern in new and emerging markets, such as Asia and Russia. In mature markets there’s a general thing about “staying in is the new going out” – we spend a greater portion of our money on interior design, big screen TVs, Playstations, cookbooks and so on – we invite friends over more than arranging to meet up with them. I think the pub or bar will always be the gold standard – you’re getting a whole experience, not just a beer. But we will all increasingly be doing more of our drinking at home.

Alan: Your references to cultures with respect for or even celebration of the three-beer buzz is really interesting to me. How, though, can an industry promote the idea that what I might call “getting a jag on” rather than “getting loaded” is the point of beer and one that we should all embrace? Doesn’t english-speaking puritanism somewhat snooker that opportunity leaving beer prone to being effectively represented as something you take to enter a fantasty land of TV advertised sports, pals and bikini-clad teens?

Pete: The reason people drink beer is to help social interaction – and you’re not allowed to say this, or even hint at it, in any promotion or advertising for beer – it’s one category where you are not allowed to tell the truth about the main product benefit. But I’ve done quite a bit of work in the UK on this subject. Many brewers now are pushing these “please drink responsibly” messages, which is fine, but a lot of people are drinking precisely because they want a break from behaving responsibly all the time. We need people to show that moderate drinking can actually be fun, rather than simply telling people not to drink as much. There’s a new campaign in the UK by Amstel that does a half-decent job of this. It ties the beer back to the laid-back attitude of the Dutch, and has lines like “drinking is just something we do between talking”, and “why rush your beer? The bar is open all night.” I think there’s a lot more that could be done along these lines. I’d like to see campaigns focusing on sentiments like “surely the best nights out are the ones you can remember.”

Again with the “Wow!” It is amazing no one is pouring big advertising money down upon my head with quality stuff like this. We remain open to offers.A big thanks to Pete for both his book and his time as well as to Knut who is one of the guys who make this beer writing stuff fun. As I said, a proper review of Three Sheets to the Wind will be up in a few days.

Like any member of the bar, I think a lot of myself. I think there are not too many documents I cannot wade through and conquer. I think I have met my match, not because it is too complex or on a topic that I cannot grasp but that it is in a language I have never come across before – economic analysis. The book’s full title in fact is The U.S. Brewing Industry: Data and Economic Analysis so I should have know. It’s that last word that gets me. You are trucking along in a chapter and, whammo!, mathematical formulae. It’s never the gaant charts or the flow charts or the pie charts or the multi-coloured graphs that get me – it’s the algebra. I think that makes what is called beeronomics econometrics. Click in the picture below and you will see what I mean.

Like any member of the bar, I think a lot of myself. I think there are not too many documents I cannot wade through and conquer. I think I have met my match, not because it is too complex or on a topic that I cannot grasp but that it is in a language I have never come across before – economic analysis. The book’s full title in fact is The U.S. Brewing Industry: Data and Economic Analysis so I should have know. It’s that last word that gets me. You are trucking along in a chapter and, whammo!, mathematical formulae. It’s never the gaant charts or the flow charts or the pie charts or the multi-coloured graphs that get me – it’s the algebra. I think that makes what is called beeronomics econometrics. Click in the picture below and you will see what I mean. But of course it is more than math that escapes me. Conversely, both authors are professors of economics at Oregon State University [Ed.: Go State!] and they explain their book in this way:

But of course it is more than math that escapes me. Conversely, both authors are professors of economics at Oregon State University [Ed.: Go State!] and they explain their book in this way:

This finally came from Amazon.co.uk after ordering it not long after mid-February, right around when I decided to create

This finally came from Amazon.co.uk after ordering it not long after mid-February, right around when I decided to create

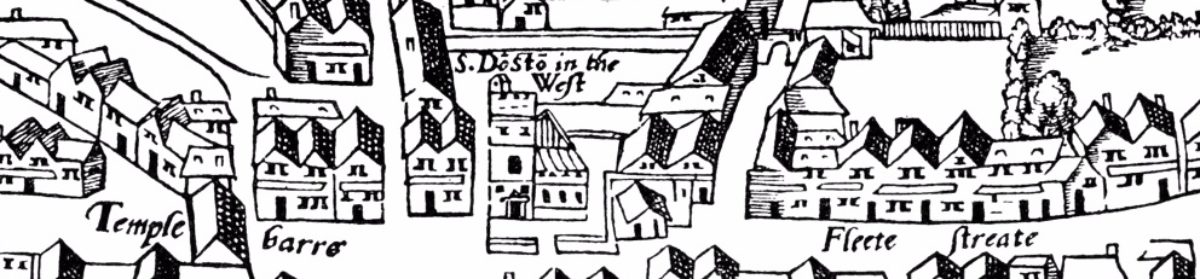

I have been working thought my review copy of this 632 page paperback published by the Royal Society of Chemistry for the best part of a month now. It is fascinating. Likely the best book on beer I have ever read. Clear, comprehensive and incredibly well-researched, this book contextualized beer and related beverages in the cultural and scientific world contemporary to any given era from pre-historic cave dwellers to the modern era and CAMRA. Yes, insert your joke of convenience now…

I have been working thought my review copy of this 632 page paperback published by the Royal Society of Chemistry for the best part of a month now. It is fascinating. Likely the best book on beer I have ever read. Clear, comprehensive and incredibly well-researched, this book contextualized beer and related beverages in the cultural and scientific world contemporary to any given era from pre-historic cave dwellers to the modern era and CAMRA. Yes, insert your joke of convenience now…