Martyn made a very important observation the other day in the comments:

…coming-of-age ales were certainly being brewed then, and such brewings look to have increased over the next 40 or more years, though that may just be an artifact of the increasing number of newspapers being published.

We are slaves to records. As I have noted before, I am very irritated by records. It is not just that I am subject to the decisions of what gets scanned from the pool of records. I am dependent on what was recorded in the first place. It is important to appreciate that it is astoundingly good to be able to find newspaper ads from New York in the 1750s not just because the newspapers are that old but because, in as real a sense, they are that new.

Newspapers only come into being in the sense we know them today in the first half of the 1700s and, really, at the latter end of that era. One of the best of the early English periodicals considered a daily newspaper was, as any one who studied English Lit should know, The Spectator published by Steele and Addison in the first half of the 1710s, the point where last of the Stuarts under Queen Anne meets the first of the Georgians. Through The Spectatorthey explored Enlightenment values as well as meaning of their toy, the possibilities of the medium. Fortunately, we can explore their explorations as the entire thing has been put on line at Project Gutenberg with an extremely handy key work topical index. As with resources like the scans of New York newspapers I have been digging through in the last two months or the searchable databases of the law cases found in the English Reports or the proceedings of the Old Bailey online, we are both grateful for and limited by the work of the good people who select which records to scan for public use.

Unlike those other databases, however, The Spectator was not particularly geared to the tastes or describing the habits of the beer-drinking end of contemporary society. The dedication to the first issue of the journal to The Right Honourable John Lord Sommers, Baron Of Evesham states that it “endeavours to Cultivate and Polish Human Life, by promoting Virtue and Knowledge, and by recommending whatsoever may be either Useful or Ornamental to Society.” Still – and as something of a great-grandparent to Tom and Bob a century later – there was an interest in describing the world of London which lay before them even as they evoked classical poetry in the search for a higher ethical lens through which to view it. In doing so, they did make some observations of the beery life. In issue no. 436 from Monday, July 21, 1712 we read about a visit to…

… a Place of no small Renown for the Gallantry of the lower Order of Britons, namely, to the Bear-Garden at Hockley in the Hole1; where (as a whitish brown Paper, put into my Hands in the Street, informed me) there was to be a Tryal of Skill to be exhibited between two Masters of the Noble Science of Defence, at two of the Clock precisely.

It is not a boxing match. It is a duel, a sword fight, the challenger stating in accepting the opportunity that he was only “desiring a clear Stage and no Favour.” The space has a pit and galleries. It is packed with humanity, gawking and flinching with every slash and wound. There are no references to drinking but a footnote leads to a description of the venue:

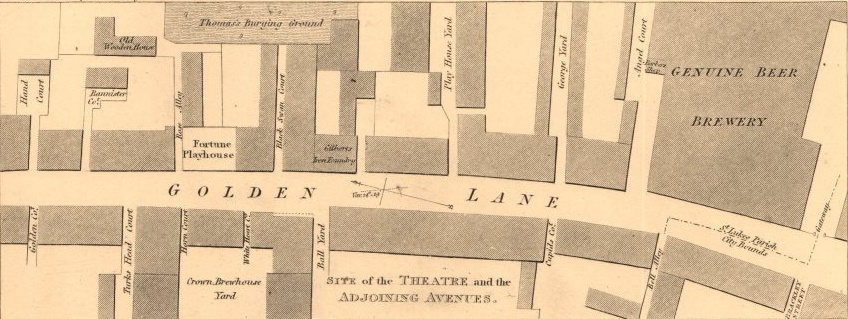

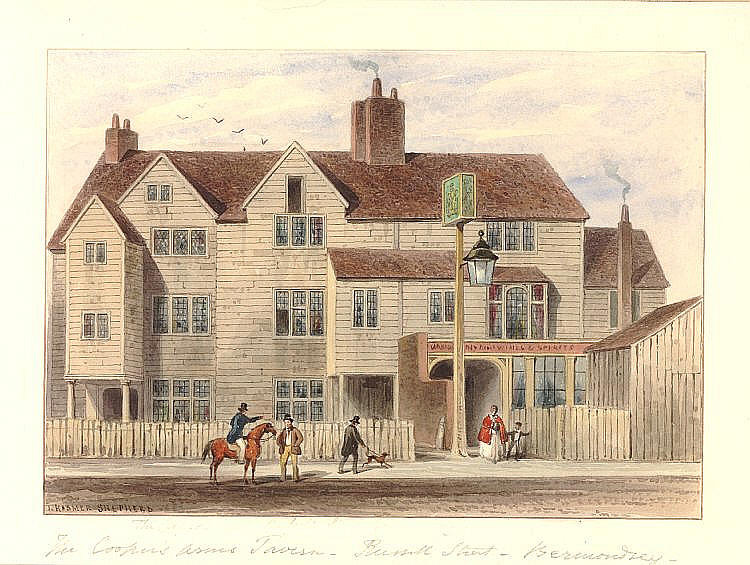

Hockley-in-the-Hole, memorable for its Bear Garden, was on the outskirt of the town, by Clerkenwell Green; with Mutton Lane on the East and the fields on the West. By Town’s End Lane (called Coppice Row since the levelling of the coppice-crowned knoll over which it ran) through Pickled-Egg Walk (now Crawford’s Passage) one came to Hockley-in-the-Hole or Hockley Hole, now Ray Street. The leveller has been at work upon the eminences that surrounded it. In Hockley Hole, dealers in rags and old iron congregated. This gave it the name of Rag Street, euphonized into Ray Street since 1774. In the Spectator’s time its Bear Garden, upon the site of which there are now metal works, was a famous resort of the lowest classes. ‘You must go to Hockley-in-the-Hole, child, to learn valour,’ says Mr. Peachum to Filch in the Beggar’s Opera.

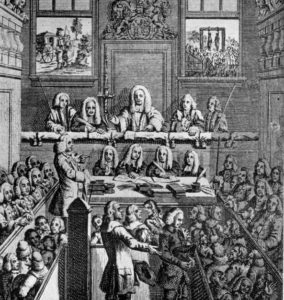

Ray Street still exists. Sounds very much like the area around London’s Golden Lane from about the same time. At the other end of the social scale and more often frequented by the regular readership of The Spectator was the club. In the recent post on Georgian mass drinking, I referenced the coming of age celebrations for the twenty-first birthday of Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham. Another thing he did on reaching that milestone, other than unleashing 10,000 hangovers, was to join clubs and in particular White’s, the Jockey Club and the Royal Society. In issue No. 508 from Monday, October 13, 1712, The Spectator – which are described in general in issue no. 9 – dealt with a certain problem one found at these gatherings often held in otherwise public spaces, the Tavern Tyrant:

‘Upon all Meetings at Taverns, ’tis necessary some one of the Company should take it upon him to get all things in such order and readiness, as may contribute as much as possible to the Felicity of the Convention; such as hastening the Fire, getting a sufficient number of Candles, tasting the Wine with a judicious Smack, fixing the Supper, and being brisk for the Dispatch of it. Know then, that Dionysius went thro’ these Offices with an Air that seem’d to express a Satisfaction rather in serving the Publick, than in gratifying any particular Inclination of his own. We thought him a Person of an exquisite Palate, and therefore by consent beseeched him to be always our Proveditor; which Post, after he had handsomely denied, he could do no otherwise than accept. At first he made no other use of his Power, than in recommending such and such things to the Company, ever allowing these Points to be disputable; insomuch that I have often carried the Debate for Partridge, when his Majesty has given Intimation of the high Relish of Duck, but at the same time has chearfully submitted, and devour’d his Partridge with most gracious Resignation. This Submission on his side naturally produc’d the like on ours; of which he in a little time made such barbarous Advantage, as in all those Matters, which before seem’d indifferent to him, to issue out certain Edicts as uncontroulable and unalterable as the Laws of the Medes and Persians. He is by turns outragious, peevish, froward and jovial. He thinks it our Duty for the little Offices, as Proveditor, that in Return all Conversation is to be interrupted or promoted by his Inclination for or against the present Humour of the Company.

Dear God in Heaven, a prig of the highest order. A curator. A beer communicator. Who knew such things were suffered across the centuries? The publishers were clearly against such things and in issue no. 201 from Saturday, October 20, 1711 wrote about temperance at a point in history closer to the Puritans than the Victorians, setting the scene in this way:

It is of the last Importance to season the Passions of a Child with Devotion, which seldom dies in a Mind that has received an early Tincture of it… A State of Temperance, Sobriety, and Justice, without Devotion, is a cold, lifeless, insipid Condition of Virtue; and is rather to be styled Philosophy than Religion. Devotion opens the Mind to great Conceptions, and fills it with more sublime Ideas than any that are to be met with in the most exalted Science; and at the same time warms and agitates the Soul more than sensual Pleasure…

Interesting stuff, such putting of passion in its place – the emotions of a child. Thoughts on temperance as we understand it and which get fairly specific about drinking were further developed in issue no 195 from just a few days before on Saturday, October 13, 1711:

It is impossible to lay down any determinate Rule for Temperance, because what is Luxury in one may be Temperance in another; but there are few that have lived any time in the World, who are not Judges of their own Constitutions, so far as to know what Kinds and what Proportions of Food do best agree with them. Were I to consider my Readers as my Patients, and to prescribe such a Kind of Temperance as is accommodated to all Persons, and such as is particularly suitable to our Climate and Way of Living, I would copy the following Rules of a very eminent Physician. Make your whole Repast out of one Dish. If you indulge in a second, avoid drinking any thing Strong, till you have finished your Meal; at the same time abstain from all Sauces, or at least such as are not the most plain and simple. A Man could not be well guilty of Gluttony, if he stuck to these few obvious and easy Rules. In the first Case there would be no Variety of Tastes to sollicit his Palate, and occasion Excess; nor in the second any artificial Provocatives to relieve Satiety, and create a false Appetite. Were I to prescribe a Rule for Drinking, it should be form’d upon a Saying quoted by Sir William Temple; The first Glass for my self, the second for my Friends, the third for good Humour, and the fourth for mine Enemies. But because it is impossible for one who lives in the World to diet himself always in so Philosophical a manner, I think every Man should have his Days of Abstinence, according as his Constitution will permit.

Sensible advice. And, as you will note, one that is pretty much in line with the best sort of recommendations today. I will trawl through the many issues and see if I can come up with any more timely references. In the meantime, remember: the fourth for mine Enemies. Excellent advice.

I’ve heard you. More tales of Cripplegate crime related to beer from the records of the Old Bailey. And why not? It’s good clean fun, in it? Let’s dissect the trial of Michael Martin and Hannah Farrington for grand larceny held on

I’ve heard you. More tales of Cripplegate crime related to beer from the records of the Old Bailey. And why not? It’s good clean fun, in it? Let’s dissect the trial of Michael Martin and Hannah Farrington for grand larceny held on  People don’t give municipal records the respect they deserve. Where the rubber hits the road, that’s what a municipality is. Consider this from the

People don’t give municipal records the respect they deserve. Where the rubber hits the road, that’s what a municipality is. Consider this from the