This has been a bit of a brain worm for me for a while. No, not that kind. The other kind. And for a longer while, I’ve been reading about how, before a certain point, all English beer and perhaps elsewhere was brown and smokey. But, quite rightly, the other day I was righteously snapped at for referring to the one post I have written on the idea. I should do a better job that that if I am going to get any sort of passing grade. So, here are some ideas that I am plunking together now. This is not to be definitive. I am showing my work and will build it upon going forward:

• Mid-1200s: In the first half of the 1200s, when England and northern France were under one government but still two cultures, Walter of Bibbesworth wrote Le Tretiz, an English-French primer to teach Anglo-Norman children about life and language. He describes the things in the world including ale making. A current edition of the book ishere. This is a translation from which we find this passage about malting:

Now it would be as well to know how to malt and brew

As when ale is made to enliven our wedding feast.

Girl, light a fennel-stalk (after eating some spice-cake);

Soak this barley in a deep, wide tub,

And when it’s well soaked and the water is poured off,

Go up to that high loft, have it well swept,

And lay your grain there till it’s well sprouted;

What you used to call grain you call malt from now on.

Move the malt with your hands into heaps or rows

And then take it in a basket to roast in the kiln;

Baskets, big or little, will serve you in plenty…

That tells us the basics of malting in a way that one commentator states “…medieval malting was, except for the lack of mechanical processing equipment, essentially identical to modern techniques.” Maltings from the 1200s were discovered this year in Northampton.

• Mid-1300s: One hundred years and more after Walter of Bibbesworth, there is a record that confirms, ale was not uniform within a single local market for as reasonably a long time as one needs to consider it a hell of a long time. In 1378 or so, in a moral narrative called Piers The Poughman at least three sorts of ale: thin or mean ale, good ale and best brown ale. He also uses the phrase “halfpenny ale” but that may well be good ale. Variety of ale brewing must include consideration of the potential for variety in malting techniques.

• Mid-1500s: As discussed in February of 2013, in his “Dietary” of 1542, Andrew Boordemade himself clear about what he considered was the best ale:

“Ale is made of malte and water; and they the which do put any other thynge to ale than is rehersed, except yest, barm, or goddesgood doth sophysicat there ale. Ale for an Englysshe man is a naturall drinke. Ale muste have these properties, it muste be fresshe and cleare, it must not be ropy, nor smoky, nor it must have no wefte nor tayle. Ale shulde not be dronke under .V. dayes olde. Barly malte maketh better ale than Oten malte or any other corne doth…

Not smokey. Pretty clear statement.

• Later-1500s: In this 2004 report on an archaeological excavation of a medieval malting kiln it is stated:

The fuels used in the malting process were documented in 1577 by William Harrison, who wrote: “In some places it (the malt) is dried at leisure with wood alone, or straw alone, in other with wood and straw together, but of all, the straw dried is the most excellent. For the wood dried malt, when it is brewed, beside that the drink is higher of colour, it doth hurt and annoy the head of him that is not used thereto, because of the smoke.”

Notice that again we see grades of now hopped beer just as we did in 1378 but it is not quality of strength that differentiates but the quality of the malt. And wood-kilned malt is noted to be both darker and the means to make a poorer beer – because of the smokey quality wood added. Harrison published his book A Description of England in 1577. Here is a full copy of the text posted by Fordham University in which you will find this: “The best malt is tried by the hardness and colour; for, if it look fresh with a yellow hue, and thereto will write like a piece of chalk. Chalk is, you will note, pale.

• Late 1500s to early 1600s: Also as stated before, there was something of a crisis in malt and fuel supplies as far back as the mid-1500s:

…the forests around York had greatly diminished and receded. Chiefly for this reason the malt kilns were in 1549 closed for two years and a survey of disforestation for eight miles around was instituted. At this time, too, the commons included the dearness of fuel in their bill of grievances and ten M.P.s were asked to seek a commission from the king to check disforestation.

The crisis of English deforestation led to a search for fuel alternatives and the main alternative was coal. The timber crisis was most acute in England from about 1570 to 1630 during which making coke from coal was invented.

• Mid-1600s: In an edition of A Way to Get Wealth by Gervase Markham from 1668, a book first published in 1615 we have an opinion on the preference for straw… and not just any straw:

…our Maltster by all means must have an especial care with what fewel she dryeth the malt; for commonly, according to that it ever receiveth and keepeth the taste, if by some especial art in the Kiln that annoyance be not taken away. To speak then of fewels in general, there are of divers kinds according to the natures of soyls,and the accommodation of places-in which men live; yet the best and most principal fewel for the Kilns, (both tor sweetness, gentle heat and perfect drying) is either good Wheat-straw, Rye-straw, Barley-straw or Oaten-straw; and of these the Wheat-straw is the best, because it is most substantial, longest lasting, makes the sharpest fire, and yields the least flame…

Again, as Harrison half a century before, you have grades of malting based on the fuel used but now not just wood or straw are described but in this passage four separate sorts of straw. But Markham continues. After these light grain straws he lists fen-rushes, then straws of peas, fetches, lupins and tares. Then beans, furs, gorse, whins and small brush-wood. Then bracken, ling and broom. Then wood of all sorts. Then and only then coal, turf and peat but only of the kiln is structured to keep the smoke out of the malt. If you go back to that 2004 archaeological report you will see a reference to evidence of that sort of malt kilning in practice in the 1400s: “… [A] charred deposit overlying the brick floor of the cellar was sampled and found to comprise mainly charcoal fragments from narrow twigs, several straw culm nodes and occasional charred weed seeds.” You can learn more about culm nodes here.

• Late 1600s: In his book A New Art of Brewing Beer, Ale, and Other Sorts of Liquors…published in 1690, Thomas Tryon discusses malting. Large parts of the book was reprinted in the 1885 text Malt and Malting: An Historical, Scientific, and Practical Treatise… by Henry Stopes. Tryon confirms the ascendancy of coke over straw due to its “gentle and certain heat.” Straw, he has to admit, is still a close second but depends more on the skill of the maltster. Wood kilning is called unnatural in that it leaves a smokey taste.

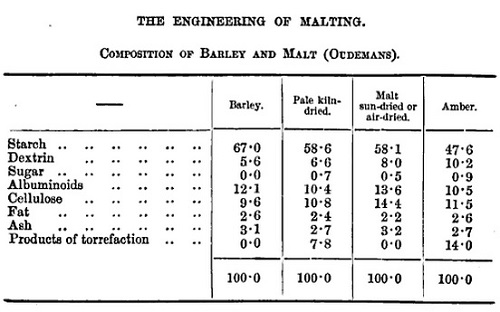

• Late 1800s: A big jump in time to the document from which that table waaaaay up top comes from page 66 of the Transactions for 1884 of the Society of Engineers based in London, England. That table is found in an article “The Engineering of Malting” read by one Mr. H. Stopes at the meeting of that organization. He also read it at the eleventh meeting of the Society of Arts on 18 February 1885. In his article, Stopes describes the malting process briefly in this way: “The English system, briefly, is steeping corn in an open vessel, germinating it upon flat exposed floors at very shallow depths, and drying upon an open-fire kiln with single floor at from nine to twenty-one days after steep.” As noted above, that sort of description could have been written by Walter of Bibbesworth 650 years earlier because the making of malt was an incredibly stable practice. He goes on to describe many sorts of malting he has witnessed including the most basic:

The simplest form of malt-house possessing any capacity for work is a plain two-story building, having attached to it a kiln or drying-house, and consisting of a ground floor of clunch, a brick steeping-cistern, and a first-floor of timber, with or without partitions for separating the stored grain or malt. The only implements are a wooden shovel and a winnowing-fan or sieve to separate the roots or “combs ” from the malt prior to its use in the brewhouse. The author has seen malt made in Italy in an open court or loggia, where the barley was steeped in a tub, allowed to germinate upon the stones in the open air, and dried in a small lean-to building, with only a hole in the roof for the exit of smoke and vapour. This was furnished with a floor of perforated sheet iron and a furnace similar to that used under an ordinary washing copper in an* English scullery. Even more primitive operations are performed in Nubia, as there millet, when malted, is dried in the sun. Such rude malteries Concern us only so far that they occupy the lowest end of the scale, and indicate the necessity for moisture, growth, and curing or drying, the three essential conditions of making malt.

Sun dried malt. That’s be pale. Stopes does not really explain his table. But he includes a column for sun-dried or air-dried malt as opposed to kiln dried. And shows that it, like plain barley, it contains no products of torrefaction. Torrefaction is toasting, roasting, etc. He does however state that kilning pale malt and amber malt is a difference of 200° to 240° F and that the time for malting is counted in days. Plenty of time to control the process. Not something in 1885 that needed scientific instruments. And if not in 1885 likely not in 1385.

I am going to keep working on this and posting updates. I may also be seeing this rudimentary traditional pale malt production evidenced in frontier New York in the first decade of the 1800s. I need to think more about that. And all of this. Suffice it to say, I am pretty certain there is evidence that the making of pale malt was not dependent on the invention of coke and that English speaking peoples in centuries past enjoyed ales which were not dark and smokey. This is in no way to say that most beer was not dark and smokey. It just seems to me that this may be found where (i) the folk are poor, (ii) resources and skills are limited or (iii) standardized industrial techniques such as – or rather concurrent to – the use of coal and coke beginning in the 1600s forced people to put up with beer that was dark and smokey. I also need to tie it into grain drying as well as bread ovens, both technologies used since the middle ages which could be overlapped with the kilning of malt.

It’s that time again. The monthly edition of

It’s that time again. The monthly edition of