As Jordan and I wrap up the writing and rewriting of our book on the history of beer in Ontario, it is interesting to go back and revisit stretches I wrote a couple of months ago. Of all the bits in the book from 1610 to today, I had not expected the mid-1900s to be all that thrilling when we signed the publishing contract. Not the case. The pace of social change in the second quarter of the century alone occurring along with the advance of modernity could give you whiplash. Certainly at the heart of that time is the massive fact of World War II but the flow of cultural change was only accelerated by the war. This was reflected in both commercial restructuring of the beer market and shifts in public perception of the role of beer in the community.

Boak and Bailey invited us all to post some long writing this weekend so, in support of an increase in new long writing related to beer and brewing – including new forms of writing – I give you excerpts from a late draft of Ontario Beer: A Heady History of Brewing from the Great Lakes to the Hudson Bay. Final tweeks continue…

**************

In 1927, at the close of the Province’s dalliance with prohibition, Brewers Warehousing Co. Ltd. was founded as a brewers’ distribution co-operative. The provincial government retained control of the sale of wine and spirits through the LCBO, but beer, with its lower alcohol content, could be distributed by the hundreds of mom-and-pop stores. Initially, the brewers were involved only in wholesale operations, jointly warehousing and distributing their product to stores operated by private contractors. But in 1940, the brewers bought out the contractors and took over the stores, changing their name to Brewers Retail Inc. The stores were later renamed, creatively, The Beer Store…

Labatt also took its place in the war effort. In 1943, it was reported that not only were patriotic efforts such as war bond drives undertaken but trucked shipments were moved back to railroads while a trade school for army motor mechanics was operated out of the brewery’s garage. The brewery also ran a series of weekly panel cartoons on good citizenship standards under the title “Isn’t It The Truth by TI-Jos”. Topics included household prudence, supporting price controls, rumour mongering as treason as well as the evils of the black market. In doing so, the brewery clearly was associating itself with middle class as well as patriotic values…

Wartime on the home front changed social attitudes to public beer drinking. Higher employment and earning levels increased disposable income. Hotels serving beer to men and women no longer carried a dangerous air so much as a patriotic one. Increased accommodation for beer sales also served the financial interests of business and governments during the war. Beer sales more than doubled during the war years and the Federal excise tax on each gallon of beer brewed increased by 36%. Further, a difference in the relative level of taxation in Ontario caused a significant shift in drinking patterns to beer from spirits.

Two forces combined to impose upon the expansion of beer sales in the second half of the war: a renewed temperance movement and resource scarcity. Under direction of the Prime Minister Mackenzie King, temperance as a countervailing patriotic theme was promoted causing a public clash between King and EP Taylor. At the same time, the national Wartime Prices and Trade Board imposed a quota system to distribute beer as it would other commodities which created shortages. In March 1943, when Kingston received an increased allocation to reflect troops being stationed there, other communities received a reduction in their share. Overall, a 90% reduction was imposed on beer distribution, beverage room hours were restricted and, as a result, the beer casks were dry when the night shift at the factory ended. Some took to wearing “No Beer – No Bonds” buttons.

After victory was won, the topic in one of the last editions of Labatt’s “Isn’t It The Truth” series was the return of the young soldier to the family home. When mother tells him there’s no rush to get a job, he replies “I’ve been doing a man’s job for four years. Now I am all ready to get going here at home.” Now, Labatt was associating itself with the sort of moral productivity that continued into the post war boom. Life in Ontario was a worth working hard for as well as fighting for. The brewery continued that theme in 1946 in a series of ads asking Ontarians to do all try can to make tourists from the United States feel welcome with hints from “a well-known Ontario hotelman” including that in business dealings, Canada’s reputation for courtesy and fairness “depends on you!”

The new economic opportunities led to changes in Ontario’s brewing industry addressing the need for consolidation and succession in light of financial success. In 1945, Canadian Breweries falls under Argus, E.P. Taylor’s larger holding company. After spending the first years of the war at the top levels of the British effort to maximize production, Taylor had returned home in 1942 exhausted to focus on Canada’s war efforts a member of National boards as well as to prepare for the future of his brewing empire. Well before the war had ended, he had given instructions to have modernization and expansion plans in place for facilities to be ready for brewing in Waterloo, Toronto and Ottawa as soon as the fighting ended. He also moved to secure assets in the malting industry as well as in an American brewery to reduce his exposure to Canadian government policies as he took steps to meet what he believed was a post war boom market for beer.

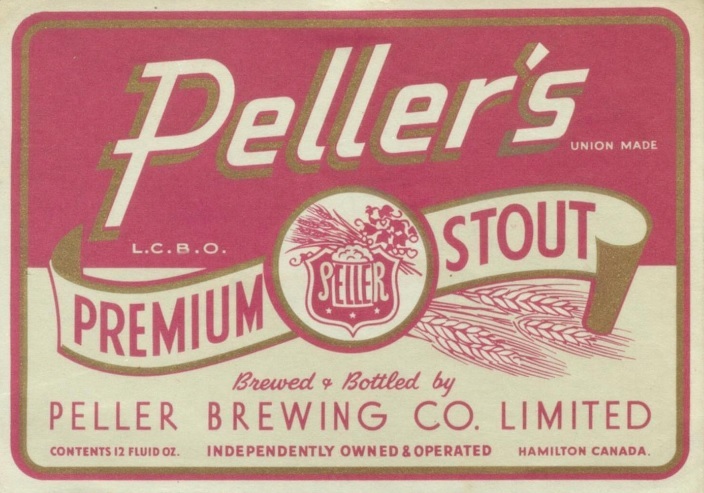

In December 1945, something happened in Ontario that had not occurred for over 30 years. A new brewery opened. The Peller Brewing Company in Hamilton. It was founded by Andrew Peller, a former brewer with the Cosgrove brewery who was backed by Hamilton businessmen. Although it operated independently for only eight years, the bricks and mortar brewing facility he built shows up a few more times in the province’s brewing history. Peller went on to open a daily newspaper in Hamilton that soon failed but moved on to create one of Canada’s first large scale wineries, makers of Baby Duck and Peller Estates brands. In brewing, he is perhaps best remembered for getting around the restriction on advertising by opening an ice company and plastering the brewery’s trucks and ads “Don’t Forget The Peller’s Ice” with the emphasis on the Peller.

The new Liquor Control laws of 1944 and 1947 divided the administrative functions of retailing alcohol from licensing. These changes created the fourth legal regime beer drinking Ontarians had to live with since the beginning of 1927. They represented a further unraveling of the temperance web of control but not an elimination. The LCBO was still able to announce in a publication in that year that there was no reason Ontarians should not be able to buy what they wished if they were law abiding and financially able. It was still the role of authorities to sift who was who. Changes to the law were brought in by another change in provincial government with the Liberals being replaced by the Conservatives of George Drew in 1943. The new laws brought in by Premier Drew sought to distance it from allegations of political patronage in the distribution of licenses and also to respond to public attitudes. In April 1944, a Gallup poll indicated that 73% of Ontarians now rejected any steps toward prohibition.

The brewing industry was interested in public opinion as well. In a private polling undertaken in 1946 and 1947, attitudes of Ontarians were measured related to beer ads in the media as well as the management of breweries and retail outlets for beer. The polling, conducted on behalf of Quebec brewers Molson, captured post war perceptions at a time of further changes to the province’s Liquor Control Act. A drop was noted from 90% to 80% on the question of whether beer was an intoxicating beverage. The shift was even bigger drop for those under 30. A great one-year jump of 40% to 88% was recorded for support for Brewers’ Retail stores with far higher marks for their management compared to hotel beverage rooms.

These opinion polls capture not only post war changes in public attitudes but also changes to the system of selling beer in Ontario which came into force on 1 January 1947. Announced the new further relaxed regulations, Attorney General Leslie Blackwell confirmed that throughout the war years beer consumption more than doubled from 24,000,000 gallons in 1939 to 51,000,000 in 1946. The old rules were described as restrictions which amounted to partial prohibition which were being “disobeyed by increasingly large numbers of otherwise law-abiding citizens.” Apparently the generation that wanted to get to work after fighting the war wanted a beer as well.

The changes in attitudes behind the polling reflects the social leveling that occurred through the years of economic depression followed by years of war. The hand of political influence was no longer an accepted norm. Nor was the moral superiority of your dry betters. Brewers were involved. Labatt was staking a claim for beer as a normal part of life by placing ads in newspapers asking for public support of the St. John’s Ambulance Society, sponsoring events like a UK food drive and organizing safe driving demonstrations at small town Legions…

At the end of the first half of the 20th century, Ontario was undergoing social transition. It was just a few years from the first human rights legislation protecting against discrimination in employment and accommodation. The Progressive Conservative party was still in the early years of a forty-two year run of uninterrupted power. The population of the province expanded over 20% in the 1940s and the economy was booming. E.P. Taylor controlled 50% of the provincial beer market compared to 20% for Labatt. At the century half way point, Ontario’s brewing industry and beer itself was changing to keep up with the race forward.