Another in the occasional series showing how my place of work was protected by a seawall… or a lake wall at least with cannon. I like how this drawing by George Harlow White from 1876 gives a sense of scale of the wall’s height.

Category: History

More International Insurance Map Brewery Fun

It was the best of times and insurance maps. It was the worst of times, you know, and… insurance maps. Errr. a tale of two cities of sorts, I suppose. From the upper left we have the Kingston Brewery as well as Portsmouth Brewing of my town from 1908 plus, to the upper right, the Albany Brewing Company, then below left Beverwick Brewing Company and, lower right, Taylor Brewing and Malting all of Albany in 1892. What can we learn from these images? Click on each image and find out for yourself. Here is what I see:

♦ UL: As discussed last August, the Kingston Brewery dates from at least 1791. The badly digitized 1824 map shows a set of buildings on the inland side of the inner harbour road. The 1908 map shows much of the same complex built up overtime. The malt kiln, laid with iron tiles, is no longer used and a lot of space is dedicated to ice houses as part of the lager operations. And there is a manure pit. Dangers which might be faced by fire crews are noted. Where a boiler might be found or a pump. The notes state that hoses are distributed meaning there is water throughout. The basic set up is a courtyard. There is a four story tower as well as a basement with a fermentation room and a stock cellar.

♦ UM: By comparison, Portsmouth Brewing in is more orderly. Based more about access to the lake than the older cross town competition. The kiln is on the land side of the property and leads into the brewery proper which leads to the bottling room. The coal and barrel sheds are separate. There is a basement and the main building is three stories high. Our commentator Steve Gates, author of The Breweries of Kingston and the St. Lawrence Valley has an excellent photo of the brewery from the next year taken from the vantage of someone under the letter “F” in “Fisher” as shown on the map. He also tells us that they had been brewing lager since 1872. Hence the ice house.

♦ UR: Next, the Albany Brewing Company neatly fills a city block as this picture from the coal shed view of 1865 to 1870 shows. I am sure there is a very good reason that hand grenades were distributed throughout the brewery for fire fighting purposes but I am not sure what that might be. Unlike the Kingston breweries above or Taylor below, there is no access to waterfront. Unlike Beverwick below, there is no train spur leading to the building. To the right center, there is a five story tower where it appears the coolers are located. The office is across the street to the south and a police station to the north. It’s in the middle of things. Looks like there are horse stalls near the coal shed that open out on to Green Street to the left of the image.

♦ LL: The Beverwick Brewing buildings appear to be more modern again. Founded in 1878, it has a rail siding… which apparently leads it to be suitable for a model railway set. The main building looks impressive. Five stories with a sixth in the attic. Brick arched ceilings on multiple floors frame fermenting tubs and beer tubs. Coolers are located in the fifth floor. A more compact footprint but, at 100,000 barrels a year, very productive and, therefore, famous. A very industrial set up compared to the others.

♦ LR: Last, good old Taylor Brewing in its elder years. The neighbouring buildings have been left vacant with only the core brewery seemingly in operation. Six stories very much oriented towards the river. When I saw this and saw the images of de Hooch yesterday, its position by the water looked like Dutch breweries lined up along the shore in Haarlem in 17th century paintings. I think that’s the building to the middle right in the image at Craig’s post on the brewery, though that was almost half a century earlier.

What does that tell us? You tell me. I see a range of brewing systems laid showing about 120 years of technological advances. Still plenty of ale brewing going on but a range of transportation methods from horse carts to ships to trains. For the most part, the breweries are all still malting at the turn of the 20th century.

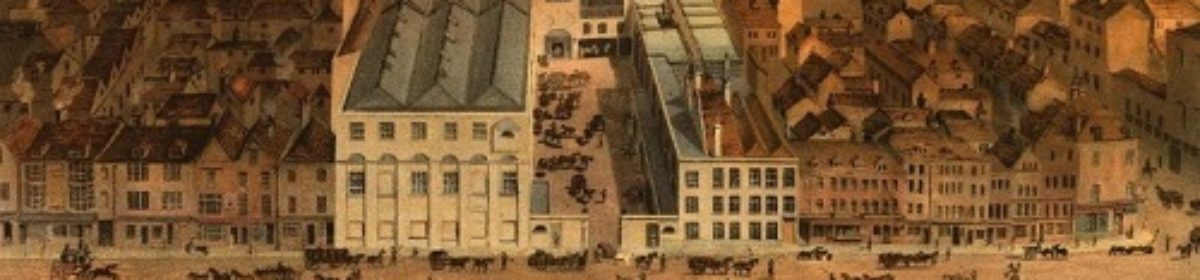

My Place Of Work About 160 Years Ago

My place of work in the 1850s when the waters lapped up to the stone wall of the market battery. As in a battery of cannon that protected the market. Because City Hall was built in the 1840s on part of the market square that he been there for decades before that. If you click on the picture you will see more detail. Like these bits:

To the left, you see the sign for “A & D Shaw” but I am not sure why there was a sign like that on the front of a government building. Were there businesses in the building, too? In the middle there is the detail to the left, a week glimpse up Market Street. To the right there is the same thing up Brock. The Market Street buildings are still there but there is no awning or porch on the south side as there was back then. An one of the buildings on Brock could be Sipps or Casa Domenico.

What Was On The Drinks Menu In 1378 Or So?

It is not often that I get to write that I was flipping the pages of Piers The Ploughman the other day but in fact… I was flipping the pages of Piers The Ploughman the other day and noticed a lot of references to drinking in Book 6. I pulled it from the back corner of the bookshelf after watching the episode of The Story of England from the BBC on life in the 14th century. This era of the plague following on the heels of a great famine saw societal disruption and population crashes. The poughman, it is explained unexpectedly only for a 21st century man like myself, was the hero of the community, the bringer of food. A morality tale, Piers joins a pilgrimage after getting his spring planting done:

…for so commands Truth. I shall get them livelihood unless the land fails, Flesh and bread both to rich and to poor, As long as I live for the Lord’s love of Heaven. And all manner of men that by meat and drink live, Help ye them to work well that win you your food.’

Notice that the winning of food by working the land earns you drink? Because the drink is ale. Made of the grain that grows in the field. So, being curious, idle and tangential – all likely sins in Pier’s worldview – I wondered what the hierarchy of drink might have been to a someone six and a half centuries back. Because what’s good about a morality play that does not list everything one way or another in hierarchies.

♦ Water. Lowest of all. The text reads at line 6.134 that “…Truthe shal teche yow his teme to dryve, Or ye shul eten barly breed and of the broke drynke…” Drag. Learn to drive the plough’s team or drink out of the brook.

♦ Thin ale is next. Wasters who will not work are punished by the reality of famine and then Piers bargains with Hunger to save them:

`Suffer them to live,’ he said `let them eat with the hogs

Or else beans and bran baked up together,

Or else milk and mean ale’ thus prayed Piers for them.

♦ Good ale. Before the character of Hunger takes his leave when the crop is in, the last year’s supplies are consumed at around line 6.300: “…Thanne was folk fayn, and fedde Hunger with the beste / With good ale, as Gloton taghte–and garte Hunger to slepe…”

♦ Best brown ale. Soon, good is not good enough as the lazy shirk again and goes off looking for something better, now available after the harvest is in and the risk of hunger has moved on as “no penny ale please them”:

Nor none halfpenny ale in no wise would drink,

But of the best and the brownest for sale in the borough.

So, not quite a style guide but clear evidence of standards, the idea that there is something worse, something good and something so much better available in town at some sort of specialty shop that you may not really need. Sound familiar?

Albany Ale: Bringing Together Different Perspectives

One of my favorite things about thinking about beer is realizing that it is actually a hugely diversified discussion even if there are significant forces trying to homogenize and standardize and prioritize the discourse. The upcoming beer school at Beau’s Oktoberfest is framing this varieties of views neatly for me. Craig has been out hunting for early central NY hops and was contacted by a home brewer who has made an attempt at one possible take of Albany Ale. Ron has been discussing the early 1800s Hudson Valley brewing logs from Vassar’s brewery and connected with alumni from the college that the brewery helped found.

One of my favorite things about thinking about beer is realizing that it is actually a hugely diversified discussion even if there are significant forces trying to homogenize and standardize and prioritize the discourse. The upcoming beer school at Beau’s Oktoberfest is framing this varieties of views neatly for me. Craig has been out hunting for early central NY hops and was contacted by a home brewer who has made an attempt at one possible take of Albany Ale. Ron has been discussing the early 1800s Hudson Valley brewing logs from Vassar’s brewery and connected with alumni from the college that the brewery helped found.

Me? Me I am most interested in tracking the cultural aspects and how they fix into the context of history. I wrote Stan an email yesterday to see if he had considered the tracking of the name of CNY hops in the 1800s and had to confirm that it was not, unlike one aspect of his focus, the DNA of the varieties that I was interested in but the names given over time to the varieties. I summarized the changes and the reasons for the changes that I have been seeing in an email back this way:

♦ Post-Revolution – economic crisis that sets CNY back for best part of three decades 1775-1805. Hessian fly affects crops during this time moving beer production from wheat to hardier barley. Dutch wheat beers in Albany becomes “Bostonian” or New England style as majority of population shifts culturally. Hardscrabble farming becomes stablized farming.

♦ Post-1812 – agricultural societies, fall fairs and some scientific farming journals start. New England “improvement” moving west. Erie canal helps this take off.

♦ 1822: some sort of crisis in hop crop in UK requires reaching out for more sources, including CNY.

♦ 1830s – Robust export ale trade well underway. CNY brewers not referring to hops according to species but local supplier / grower. Exporting via ship.

♦ 1848 – UK brewers note “American hops” in their brewing log. Not by variety. [Ron has a post on this.]

♦ 1840s-60s: large and small cluster described in CNY. Geographical named hops also being referenced like “Pompey” and “Canada”. Pompey is a town. Canada is a variety that moves south, faces a false imposter and becomes “True Canada” soon after Civil War – the arse is out of all of it and mad breeding and diversification underway. Science meets money.

Keep in mind “Albany Ale” in this sense is all about the barley beer that ruled before lager takes over in around 1875 after four or so decades of expansion. Before 1775 and likely for a bit after, it remains my belief that the Dutch wheat farming of the colonial era was logically – and in accordance with the evidence – also the source of indigenous wheat beer brewing that relied on hops that were a hybrid of local wild hops and Dutch introductions. Others may have a greater interest in the industrial era when Albany was king. Or with the actual techniques of brewing. Or discovery of the actual ingredients of the beers.

Which is great. Because that is what makes the discussion complex and interesting. No one person has it right or framed the discussion.

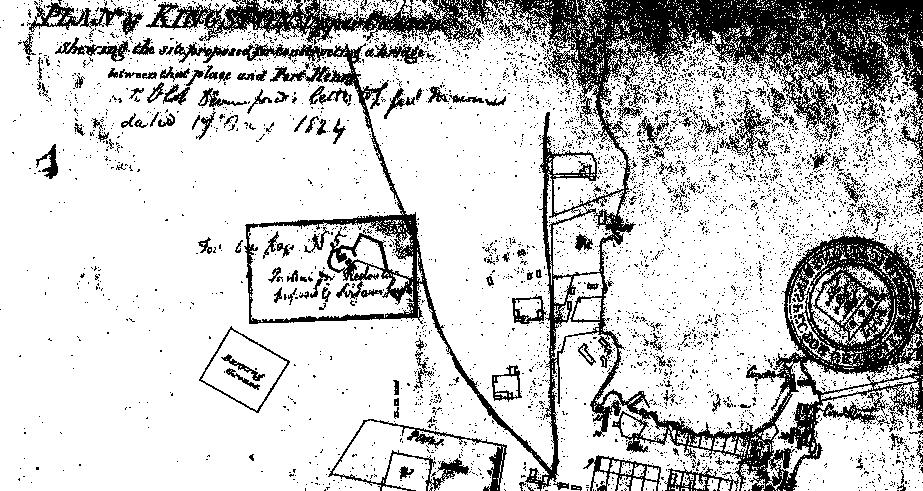

Ontario: An Early Reference To The Kingston Brewery

The funny thing about Ontario is it started as a part of Quebec. Until the division of Upper and Lower Canada in 1791, this was all the one unified colony that Britain took from France in the conquest of 1760. Settlers started moving in 1783 first from central New York in the first direct Loyalist wave, then over the rest of the decade from the eastern US seacoast as the losers of the Revolution filtered their way around up from New York, Nova Scotia and then down the St. Lawrence. An oblique reference in a land document for a Lieut. Mackay from 1794 gives an interesting hint as to the development of brewing here in Kingston, the commercial center of this new colony:

The funny thing about Ontario is it started as a part of Quebec. Until the division of Upper and Lower Canada in 1791, this was all the one unified colony that Britain took from France in the conquest of 1760. Settlers started moving in 1783 first from central New York in the first direct Loyalist wave, then over the rest of the decade from the eastern US seacoast as the losers of the Revolution filtered their way around up from New York, Nova Scotia and then down the St. Lawrence. An oblique reference in a land document for a Lieut. Mackay from 1794 gives an interesting hint as to the development of brewing here in Kingston, the commercial center of this new colony:

On May 27, 1794, a petition had been presented in Council on his behalf for “a Piece of Land about the usual Size of a Town Lot, situated on the West side of a Lot lately laid out for the Kingston Brewery, to be bounded on the North by the said Brewery on the East by a small run of Water, on the South by the Common, & on the West by the top Bank…”

The passage is from The Parish Register of Kingston Upper Canada 1785-1811, an online resource that also confirms that by 1797 it was managed by one John Darnley. That is it above shown on a map of my town from 1824. It is also shown on a map from 1865 and later additions are still there – as the 2003 photo at this post shows. There was earlier brewing in the colony but likely tied to taverns like Finkle’s in nearby Bath. Steve Gates, our comment leaver and author of the excellent book The Breweries of Kingston & The St. Lawrence Valley pegs the building of the brewery in 1793 by merchant John Forsyth but it is John’s brother Joseph who is more of the man about Kingston in the 1790s. But, as a garrison town and a depot supplying deep into the continent from the main colonial centre of Montreal, it is entirely likely that their Kingston business affairs overlapped repeatedly.

Creation of the brewery reflected some level of certainty after years of difficulty in ensuring the grain crops could supply the expanding colonial population. A 1796 letter noted in Preston’s Kingston Before The War of 1812 even speaks of the continuing infestation of Hessian Fly affecting the area. Building a brewery spoke to an expectation of peace.

“…107 Tons Of Beer And Six Tons Of Canary Wine…”

Later this summer, we are spending a few days in Baltimore. Looking forward to it in many ways including things beery… including brewing history. We know a bit about Baltimore and beer already. See, in the 1620s there was a brewery at the first Lord Baltimore’s colony at Ferryland, Newfoundland. And in their voyage of 1633-34, the Ark and Dove apparently carried 107 tons of beer and six tons of Canary wine to what would be the second Lord Baltimore’s colony at St. Mary’s City, Maryland. It would appear likely, then, that the pattern of settlement in the latter might include replication of provision seen in the former for that necessity for the community, brewing.

But can I find a list of the ships’ stores? Not a chance. There is a book The Flowering of the Maryland Palatinate from 1961 that appears to have a reference at page 15. There may even be a list of provisions in this article from the state’s historical society. But Lord Goog is either not so wicked or has not yet found a way to make a buck at displaying these full documents to me. Drag. You would think that lists of ship’s stores from early modern period trans-Atlantic sailing would be the hot item of the internets. The 1670s evidence is there for northern Canada. But Maryland? No. I blame Gen Y. I often do. I know it is easy but that’s why blaming them makes so much sense.

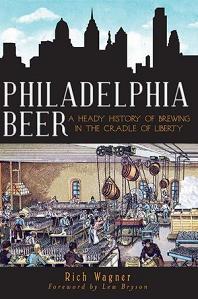

Book Review: Philadelphia Beer, Rich Wagner

As recently discussed, the past is a foreign land when it comes to US beer history. More like another planet it seems sometimes. I am not sure why this is but I suspect it has something to do with the drive to be authoritative rather than innovative when it comes to so many of the beer books being published. Sadly, there is more than enough problematic high level description of various qualities out there but far too little of the more interesting and accurate detail.

As recently discussed, the past is a foreign land when it comes to US beer history. More like another planet it seems sometimes. I am not sure why this is but I suspect it has something to do with the drive to be authoritative rather than innovative when it comes to so many of the beer books being published. Sadly, there is more than enough problematic high level description of various qualities out there but far too little of the more interesting and accurate detail.

Then one comes across a book like Philadelphia Beer by Rich Wagner – or rather just pages 17 to 34 – and all my despair falls away. Why? Because Mr. Wagner admitted and actually investigated a portion of that seemingly secret or perhaps oddly discomforting tale of pre-lager moderate to large scale ale production that not only existed but thrived in America from somewhere around the 1630s into the late 1800s. In those few pages, he identifies brewers and breweries by name, location, production and beer brands that existed not only before lager in the 1840s or so but he does the same for pre-Revolutionary Philadelphia, the city that becomes the first US capital. And in doing so, he adds credence to all that follows. I trust his writing on what comes later in the first German lager breweries, the later industrial macro-lager breweries and the craft breweries because of it.

Why have we found ourselves here? There may be a reason for this lack of collective long term memory. The introduction of lager roughly coincides with the expansion of the US from a coastal eastern nation built on a colonial footprint to the nation we know today, care of the Erie Canal and resolution of First Nation, French, Spanish and Russian control of large tracts of what are now the central and western states… and Florida. In a way, American ale was an Atlantic focused thing while lager is mid-western to Pacific. The path of lager, as Maureen Ogle so well describes, defines America as much as the wild west and California surfers so. It is in itself exceptional in all the meanings of that word. This burden of national history bears upon the topic. And it is in addition to the simple fact that a deeper longer view takes the sort of hard work that Wagner takes on himself and builds upon from the few earlier studies. Too often we only see what happens when one confuses facts as they were and the evidence that is available today.

Get yourself a copy of this book. Then, start thinking about how the structure of this small book, applied large, might change the way we see the extraordinary phenomenon that is American brewing. And might create a new tie between craft movement of recent decades and that small scale craftmanship of hundreds of years ago. And then maybe we’ll start seeing not only the similarities but maybe even the links. I had a Yuengling yesterday as it turns out.

Albany Ale: An Annotated Brewing Log From 1834

A bit of a question for you today. Above is a brewing log from just before the world of US brewing learned about lager. I won’t get into the details of whose log it is for now* as I am hoping you may be able to help draw out a few more details than I have. If you click on the image you will see my annotated notes. For the most part, I am clear on the numbers but would like to know more about the techniques involved. You will see that there are three beers made from a single mash but that the two stronger are recombined. That makes for what the brewer calls a double and a single beer. Here is what else I see:

♦ The double seems to have 104 barrels of liquor before the boil. A US barrel has 119 litres. So that is 12,376 litres.

♦ The 190 bushels of malt works out to 6460 lbs at 34 lbs a bushel of malt.

♦ The 220 lbs of hops would be local CNY Cluster hops

♦ The malt would also be local pale malt.

♦ This beer made 7 barrels of small ale and 60 barrels of double ale. I don’t understand how 68 and 36 barrels before boil makes 60 as a result. I ran the malt and liquor through a standard calculator and see the result is a 5.1% beer. But I am missing something. That much concentration should make a stronger beer. Or am I making an assumption.

♦ The notes on the opposing page for batch 140 say this is a Pale Stock NY ale. Also, it is noted that this is a particularly good batch.

♦ Unlike some other brews logged and also comments from the time, no salt is added.

Anyone handy with the abbreviations “HVG” and “HHG” at the tops of columns #10 and #12? I assume the G stands for gravity. Also, note that there are slightly different hand writing. The log is filled in over 9 or 10 days. So, the two numerals “6” in column #10 differ. Also, I am now thinking that the number in column #11 may actually be a “65” when I compare it to other numbers. That might make this a notation from degrees F rather than weight or quantity.

Anyway, all thoughts appreciated. This is part of a bigger project so I am hoping the power of the collective brain effect that the internets always promised will nudge us along. Let’s see.

*OK, it’s Vassar’s log.

American Brewing And The Pre-Lager Question

One of the odder things about the history of American brewing is the failure to get a handle on the extent to which pre-lager brewing existed before roughly 1840. Earlier this fourth of July, Jeff, who is pretty good with this stuff, described it in negative terms this way:

For centuries, it was an immigrant’s drink… Locals pretty much didn’t touch the stuff. In 1763, New England alone had 159 commercial distilleries, yet were only 132 breweries in the entire country in 1810. By 1830, the US had 14,000 distilleries, towns tolled a bell at 11 am and 4 pm marking “grog time,” and the per capita rate of consumption was nearly two bottles of liquor a week for every drinking-age adult. We only started drinking beer when another wave of immigrants, the Germans, brought it in the 1840s. Their lagered beer, in a time when no one understood the mechanism of yeast, was clean, tasty, and popular. We enjoyed a flowering of brewing in the following decades–German beer, brewed by immigrants. It was stubbed out by the great puritan experiment of Prohibition, which also says a lot about America.

Setting aside the question of who was a “local” in the pre-Revolutionary context – are we talking about Mohawks? – by any account, it is pretty clear that there was plenty of ales, beers and porters going around the US before the Revolution and even before that later lager revolution. Craig has mapped at least 18 identifiable pre-lager breweries in Albany, NY – one of the larger national brewing centres with a history there of beer that predates 1776 by about 150 years. Gregg Smith wrote an entire book entitled Beer in America: the Early Years – 1587-1840 which does not seem to get the attention it deserves. Heck, Ben Franklin himself welcomed Washington himself to Philadelphia in 1787 with a cask of dark beer.

As a Canadian, I am not sure why there is this national amnesia with our cousins to the south. Yes, there were certainly other drinks. I recommend highly the chapter on apples in Michael Pollen’s book The Botany of Desire which explains how apples were an important pioneer resource for milder cider, hard applejack as well as the sterilizing properties of alcohol. There was also a strong tradition especially at the frontier wherever it was found for home made fermentables and distilled booze. The Whiskey Rebellion of the 1790s in western Pennsylvania is called that for a good reason. But there also seems, despite the available record of ale production, a need to link light lager introduced to America in the 1830s and ’40s as being somehow something of a more American brewing genesis – even though pale light lager was at the time an unwelcome immigrants’ beverage that led to its own share of troubles. We also forget how few Americans there were in the colonial and Revolutionary times and how little of the present US they had actually settled. Beer is always part and product of a larger and a peaceful sort of economy.

American beer history is 200 years older that some would say – and far more complexly interesting, too. Last night I got to annotate a brewer’s log for an 1833 pale ale that, with a little more research, could likely be drilled down to where the field where the malt was grown. With any luck, it will be made for sampling this fall. By a Canadian brewer with pre-Revolutionary connections I won’t get into now. With a bit more luck, more of these brewing account books and day logs will be found and the actual pre-lager history of the US can be described.