The post at Jeff’s titled “A Better History of IPA“, written in response to a particularly poor piece of old school beer writing, led to comments and on of those comments led me to recall this:

From Schenectady to Albany, about twenty miles, the country is sandy and poor. We travelled at the rate of seven miles an hour, but what with our avalanche adventure, and some other detentions, it was long after midnight ere we reached the city. We had so far exceeded ordinary hours, that the Hotel was hushed in repose, and although we might certainly have raised the home, it was rather doubtful whether we should thereby have improved our condition. We found the porter dosing in the hall, and having committed our luggage to his charge, we agreed upon diving into a certain cellar, which we had observed to be still lighted up as we drove in. Here we found a good sample of low life in Albany. It was about three in the morning, and some of the party had evidently been indulging freely during the previous hours. Still there was no brutal drunkenness nor insolence of any kind, although we were certainly accosted with sufficient freedom. After partaking of some capital strong ale and biscuits, we returned to our baggage apartment, and wrapping ourselves in greatcoats and cloaks, we enjoyed a tolerably comfortable nap, until daylight again put us in motion.

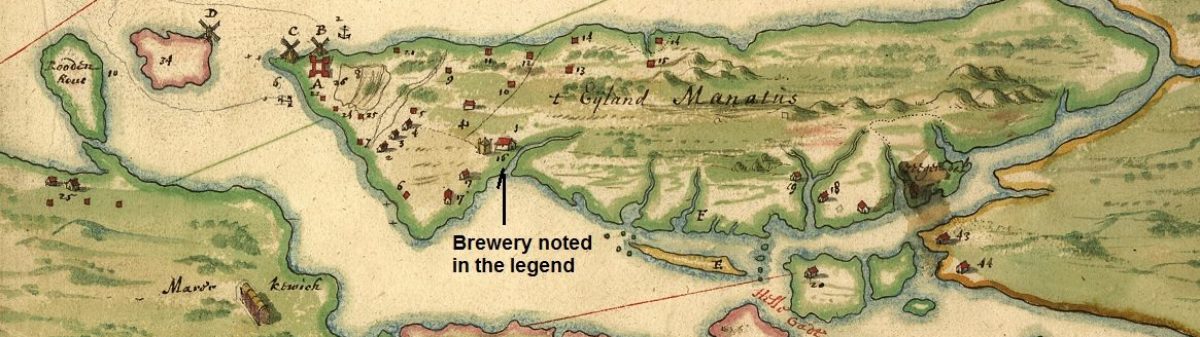

The passage is at page 192 of a travel diary from 1832, Practical Notes Made During a Tour in Canada: And a Portion of the United States by a Scot named Adam Fergusson. I love it. Diving into a cellar to find a 3:00 am party with a feed of biscuits washed down by what was likely Albany Ale of the sort discussed a few years later by the New York State Senate in hearings over adulteration charges against Hudson Valley brewers. Jordan found the diary on line and shared as part of our research for the history of Ontario we are writing and then I shared it with Craig for the bits like this that relates to Albany brewing history we are writing.

What got me thinking about that cellar party in 1832 was not Jeff’s post so much – and certainly not the underlying butchering of both history and thought – but this comment:

And where is the evidence of brewers historically using modern dry-hopping techniques, pelletizing processes, refrigeration, CO2 purging/blanketing, and other techniques for maximizing hop aroma? Just because a historical brewing log says they added 10lb/BBL of hops doesn’t meant the beer was anything like many beers are today. And the hops today are just so different that it’s not even a comparison, though you’ve already written that off and I don’t think it matters anyway in the face of the rest of the process differences. Bottom line is beer today is substantially different from the past. I don’t agree completely with Charlie’s historical take, but your critique of him doesn’t really address or refute what he wrote.

The author of the comment is, I understand, Sam Tierney who is an excellent brewer of excellent beer at Firestone Walker. There is a lot in the string of comments so read the whole thing. The purpose of this post is not to refute or even debate Sam’s point so much as explain what I understand about the point as well as to elaborate where the point leads us. Perhaps a list of observations will help me in organizing those thoughts. In no particular order…

1. Beer is both basic and complex

One thing that is entirely correct in Sam’s observations is that technical advances have played a huge role in the present day boom in good beer. The variations and expansion of sales in IPA in particular has if not led this boom it is a key identifier. It is also the case, that those technical advances are not necessary for the creation of excellent beer. How can I say that? More that anything else I know that because I am a bad brewer. It has been some time since I brewed but today with little more than buckets, a stock pot and simple speciality equipment I could brew excellent beer. With those rudimentary tools, I have made many batches of all grain beer. It is beer of quality that have been received by pals with enthusiasm. I say, however, little more because there are two key items that go a long way to ensure that excellence is achieved. I have access to very good ingredients. The best malts, top notch hops and yeasts packaged by the suppliers to craft brewers. That is important. More important, however, is the StarSan. For me, cheap and effective sanitation is the actual miracle behind modern brewing, whether at the scale of the homebrewer or that of the industrial plant that puts out craft beer or macro gak.

That being said, there are at least three things that craft brewers do that I can’t. The good brewer of good beer achieves success though the three-fold benefits of consistency, stability and efficiency. Consistency I will define as sameness from batch to batch. Stability for me means sameness in the bottle or the cask for a reasonable period of time. Efficiency means making good beer from the least resources reasonably possible. For me, Sam’s comment reflects these achievements of modernity. And important ones they are. But they are not determinative on the question to the point he states. They certainly do not add up to beer today being substantially different from the past.

2. Beer has been basic and complex for centuries

While I am researching brewing history a lot these days and even been writing about brewing history for some time, I am not a historian. I am the amateur popinjay dipping a toe in the water at best. Yet… I have seen certain things. One is certainly that the history of brewing – and especially North American brewing before and beyond the advent of lager and all it has brought – is one of the most neglected topics I have ever come across. Being a lawyer, one is something of a generalist researcher and I have had to study topics are diverse as First Nations history of Ontario and New York, the properties of concrete and the intersection of strollers and dog parts from a human rights perspective. In each area, those who have gone before have laid down reliable grounding for those who follow. By law is like that. Like beer, it as old as culture.

From my research in brewing, however, I have learned that many accepted truths and well-known assumptions are incorrect. Pale ale in the English-speaking world is centuries old. There was a very good reason for the temperance movement to come along as the past of not that long ago was a stupefying drunken place. And the American love of highly hopped strong malt ales is as old as the nation. It is not just that there is nothing new under the sun so much as what was old never really leaves us so much as alters a little as culture around it alters a lot. So we forget. We forget that in the mid-1600s, skills of the good brewers were honed likely as sharp as they are now – it’s just that the tools were not what they are now. But beer is not special in that regard. The same is true of all aspects of our culture. So just as Shakespeare scratched on vellum with a quill pen to create masterpieces, so too the ancient brewer or brewster knew

…the best and most principal fewel for the Kilns, (both tor sweetness, gentle heat and perfect drying) is either good Wheat-straw, Rye-straw, Barley-straw or Oaten-straw; and of these the Wheat-straw is the best…

Of course they did. People did not sit about moaning about how they regret not living in the future. They achieved excellence in the world around them based on the resources around them. Including with beer.

3. IPA has separate centuries-old American roots

I tweeted a tight meaningful summary of this point just yesterday:

Taylor makes very strong hoppy beer, trains Ballentine, Terry Foster recalls Ballentine, trains US craft.

Every time from here on out you see someone pretend to retreat from Twitter discussions because 140 characters cannot contain their wisdom, please remember that tweet. Except not for the misspelling of Ballantine. Let’s unpack the idea a bit.

a. Taylor. Taylor is a key figure in mid-1800s Albany brewing. He owns what was likely the largest brewery in North America around 1850. When you see a listing anywhere in the hemi-sphere for Albany Ale from the 1830s to the 1880s it is likely Taylor’s being advertised from Newfoundland to Texas to California. Craig has more.

b. Ballantine. Craig has a lot of detail under that line but a key point is that Peter Ballantine trained under Taylor before he went off to brew on his own in Neward NJ, starting a line and legacy of beer that can still be consumed in some form today.

c. Terry Foster. I wrote the post under that link in November 2004, nine years ago. Foster, among other things is the author of Pale Ale, volume one of the Classic Beer Styles series issued by Brewers Publications. At page 1 of the 1990 edition of that book, he wrote:

An impressive and highly individualistic U.S. example of this beer is (was?) Ballantine India Pale Ale. Supposedly made from an authentic 19th century English recipe, brewed to a high gravity, heavily dry-hopped and aged in oak casks, this beer has a very intense, complex aromatic character (or did have until the last few years or so).

See? The only thing Foster may have wrong is that Ballantine used an English recipe. Or not. When Americans in the 1830s figure out how to do something they are likely relying on British brewing guides but, regardless, the apply that knowledge by brewing the beer in the US. And brewing a beer that was likely a lot like beer we are familiar with today. This is not to say that this is the only source but it is a key one and one that has been disregarded or unexplored. I have no idea why.

So, there you have it. I was up at 4:45 am thinking out this post and now, eight hours later, have hand cramps. Remember. The past is amongst us. North American brewers have innovated for hundreds of years. Craft brewing is continuing that tradition and, in doing so, make beers remarkably like their forefathers. Go figure.