This first hint something stunned was up came in a tweet from Andy Crouch:

Ha ha ha true craft beer. I give up.

Now, before you jump to “haters gonna hate” have a look at this response to that tweet: “Stopped saying “craft”, feels good.” That from the first guy I heard “haters gonna hate” from. You know big graft has already lost its grip when a man of faith such as an Alstrom mocks it. What’s the news they are discussing? This:

…Stone will be participating in True Craft as a founding member. The new venture has received an initial $100,000,000 brought forth from an investor group committed to the long term model. True Craft will welcome a handful of the best craft brewers in the business alongside Stone Brewing. Each brewery may participate in True Craft and in turn the company will provide minority investments to its members with minimal stipulations. All breweries will be aligned in the philosophical mindset of banding together to preserve craft while retaining full soul and control of their businesses for years to come. “This is about setting up a consortium so we can not just survive, but continue to thrive in a world in which craft is being co-opted by Big Beer,” said Steve Wagner, Stone President and co-founder. “This allows companies like Stone to follow an ethos that involves independence and passion for the artisanal. By investing in True Craft now, we can be confident that our vision is locked in beyond our professional lifetimes and we feel privileged to help others in our industry do the same.”

One of the more disappointing things about writing about beer for over a decade is how many folk writing about beer have little interest in studying history or understanding business – let alone tackling the reality that beer and brewing sits in an very wide intersection of human activity that has been regulated in our tradition for at least the best part of a thousand years. It’s a story like this that has the wheels, however, to interest an amateur brewing historian who practices in public construction and commercial law. Let me explain.

See that figure up there? $100 million. Sounds like a lot. Sounds like someone thinks that will make some sort of change. Don’t count on it. Long time readers will recall an early post of mine sweetly titled “Beer is Bigger Than…” in which I pointed out that all beer in Canada in 2003 was worth $7,864,437,000.00. It was bigger than wheat, charity and the Government of Nova Scotia. Thirteen years later, not much has changed. Beer is big and $100 million USD probably now represent maybe 1.5% of the Canadian brewing market. Expect the US market to be ten times that and in the NATO region market maybe double that again. In the global marketplace the fund is piddly. About the cost of building two 18 story apartment buildings or one water treatment plant for a small city. And that’s in Canadian funds – which is about 80% of US right now.

Not only is the fund small, notice also that it is an investment fund. It’s not a grants fund. The capital is to be recovered. A month ago, Jim Koch of Boston Beer was telling a tale of woe about the effect rapacious private equity will have on craft beer. We are told “Funds have finite lives…When those fund lines get to the end, [fund managers] have got to sell those assets.” It’s reported as doomsday. They sky is falling. Well, if it’s true of a professional fund then that reality is going to be true of this one, too. Interest will have to be paid and at some point the fund will cash out. These monies, too, will need to be repaid – passion or no passion.

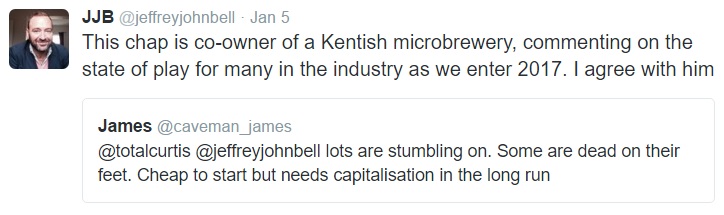

And it’s also up against clever competition. Recently, the Boston Globe profiled private equity firm Fireman Capital Partners, the investment folk behind the expansion of Oskar Blues and the cash injection into Florida’s Cigar City Brewing. You think those guys are shaking in their boots over the prospect of a rival fund based on Stone’s ethos? Hardly. The experienced private equity players will out bid and out run their deals. It’s their business, not a hobby or a faith-based act of grace. While True Craft may “welcome a handful of the best craft brewers in the business alongside Stone Brewing” we are all too well aware that many of the best craft brewers have already made their minds up and moved elsewhere – whether under the wing of big beer or in partnership with existing private equity.

Finally, look again at one last loony line in the press release: “This allows companies like Stone to follow an ethos that involves independence and passion for the artisanal. By investing in True Craft now, we can be confident that our vision is locked in beyond our professional lifetimes…” Question #1: is Stone the central recipient of funding or an investor in the dreams of others? What is really going on? Question #2: can you see the oxymoron? How can one be independent and also go along with a “vision… locked in beyond our professional lifetimes” when that vision is someone else’s vision? The guy looking forward to retirement’s vision. Who needs that? The greatest thing at the moment in good beer are the thousands of actual small brewers coming forth independently in a complex wave of entrepreneurial vitality. They don’t need Stone or its money. It is a rather modest proposition to set up a small brewery and, in the right market, one that usually is greeted with enthusiasm by the buying public. Unless you suck.

It’s the same as it ever was. Same as it ever was. At the macro level, brewing is a business that undergoes continuous change that is usually misinterpreted as failure. Folk say temperance caused the collapse of breweries leading up to prohibition. It was actually the explosion of the railroad network in the latter 1800s which unleashed basic commercial efficiencies. Hooray for cheaper good beer for all! Folk suggest the old guard of big craft represent some sort of guru class who carved a niche of good beer forgetting that the entire world of consumer goods has raced towards diversity and excellence over the last four or five decades. The big craft era of 2005-15 is relatively late to the game. And, let’s be honest, if these guys didn’t become the millionaires and billionaires someone else would have. It’s not like they invented beer. Folk will say that good beer is in crisis and point to this odd news as some sort of life raft in an ocean of evil big beer and big money. Have none of it. This is just the new boss meeting the old boss all in the great cause of money. Which is good. Because that is success.

Rejoice. Big craft is dead. Brewing continues to move on and on, becoming more affordable and more excellent and more diverse and more interesting because this era of craft is dead.

Ah, my least favorite glass ever meets my favourite brewery of 2016. I got the Kwak glass likely the best part of

Ah, my least favorite glass ever meets my favourite brewery of 2016. I got the Kwak glass likely the best part of  Ah, Mr. Chimphead. A serious point must be about to be made. But being August, there is not much out there to read, not much worth writing about. People rightly have other things to do. But Bryan Roth has posted a

Ah, Mr. Chimphead. A serious point must be about to be made. But being August, there is not much out there to read, not much worth writing about. People rightly have other things to do. But Bryan Roth has posted a