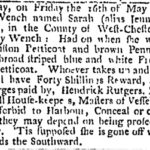

What a sad image to come across. A human for sale. It’s from from the 15 April 1734 edition of the New York Weekly Journal. Apparently the sale didn’t come to pass as she was still for sale half a year later. Unless that is another unnamed woman for sale with the same skills. The colonial economy of the Province of New York included slavery. It’s a fact you have to keep in mind when researching the colonial brewing economy. This is not to point fingers. It’s just tragic reality one cannot reach back and undo. There were people enslaved here in my town well after the relocation of the Loyalists from New York to here – some even fighting with their enslavers on behalf of the Crown. The North American economy simply included the use of and trade in forced labour in areas other than what became the Confederacy. Brewing business included. People, both slaves and indentured, were commodities.

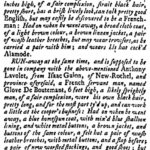

How did you deal with oppressive conditions in the 1700s? Options were limited and often at the drastic settling in those times. You could kill your captain if he earned himself a mutiny. You could run away. Look at the first thumbnail. Henry Rutgers, brewer, posted a notice in the New York Mercury of 9 June 1760 offering a reward for a runaway (aka freedom seeking) woman named as Jenny. And it wasn’t just slavery. Under the other thumbnail you will see another notice. In 1753, two indentured servants – both Frenchmen – ran and the one was noted as being a cooper. A maker of barrels. And it was not only about economic oppression. A brewer could even escape from jail – although I am not sure where a brewer named Sybrant Van Schaack could hide.

These sorts of hardships were the lot of mankind through most of time and space. I am sure there are enslaved brewers still today. But in the 1600s, 1700s and even into the 1800s, New York had a special sort of restriction on liberty. The system of patroonship. The patroons were a Dutch introduction, a form of landed gentry in the Hudson Valley which somewhat dysfunctionally off-setted the colonial power of the Governor of the West India Company. Like the seigneurial system in New France, these landlords controlled large tracts with the goal of maximizing economic output – including, as we stated in our book, the brewing trade:

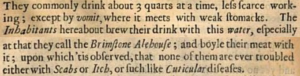

In 1643, the patroon van Rennselaer contracted Evert Pels to work as a public brewer for six years between 1643-1649, in the colony at what would become the colonial brewery in Greenbush. Pels had recently arrived in the colony on the ship Houttuyn or “the woodyard”. He traveled in the company of a Rev. Megapolensis and family a surgeon named Abraham Staes, as well as more farmers, and farm-servants. The ship carried a great volume of supplies for the colony including four thousand tiles, and thirty thousand stone for building. It also carried between 200 to 3000 bushels of malt for the brewery of Mr. Pels.

The Manor of Rensselaerswyck was likely the most successful of these estates and certainly the most relevant to Albany. The original plan for the brewery was that it would supply all the beer for the entire New Netherlands enterprise. The founder of the Rutgers clan, Rutgers Jacobson, brewed for the patroon. In no small part due to the support given to the Federalist leadership during the Revolution, the system lasted through eleven or twelve patroons over 200 years until the 1850s when the last leases were sold off by the van Rensselaer family. Being a controlled community for much of that time, the patroon ultimately controlled the crops as well as the infrastructure like breweries. The fourth patroon married the daughter of a brewer, Maria van Cortlandt, who herself set up a brewery on the estate in 1662. For generations, control of all aspects of the estate’s economy generated vast profits. The last patroon, Stephen III, is considered the tenth most wealthy American of all time. Not the sort of thing a Jeffersonian expected would exist still half a century after the Revolution was won. Rents were to be paid in wheat, a crop which was especially not well suited to the western portion of the estate. Also, the patroon retained all water rights. Not exactly the circumstances which might trigger individual investment in an independent brewery.

The system failed after the Panic of 1819 and the collapse of wheat prices. Tenants declared they were living in a form of slavery but nothing changed until, in the 1840s, there was open revolt. The Anti-Rent or Helderberg War was well underway. Once won, it didn’t take long for the region’s hop plantations to take off. The NY state crops centered in the region expanded nine-fold from 1840 to 1860. Today, Deitrich Gehring is growing hops and barley in the same lands of Helderberg for the Indian Ladder Farmstead Brewery And Cidery. I have met Deiter, through Craig, a few times. He has co authored The Hop Grower’s Handbook: The Essential Guide for Sustainable, Small-Scale Production for Home and Market with Laura Ten Eyck. Such are the fruits of freedom.

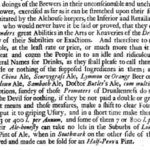

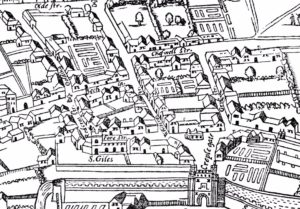

After writing my notes about

After writing my notes about

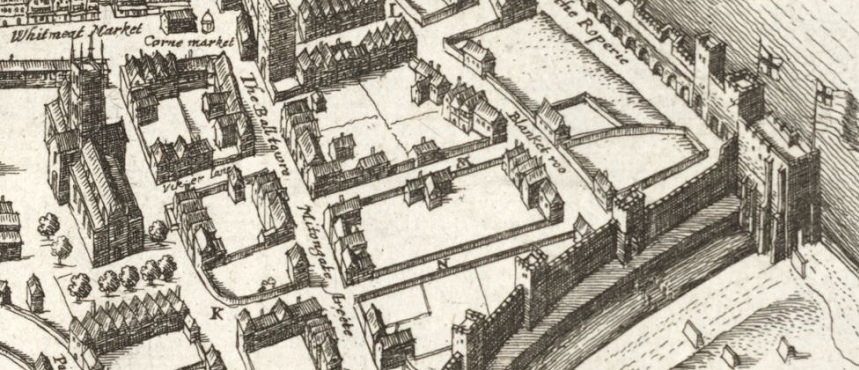

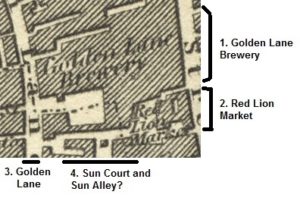

Up there, that is a detail from the

Up there, that is a detail from the