Ah, the Hanseatic League. I posted about the Hanseatic League earlier this year, pointing out how it was likely the conduit for the first introduction of hopped beer into England – and, by implication, not the Dutch. I think that might be the case for no other reason that the Dutch were introduced to hopped beer by shipments from the Hanseatic League, the Renaissance corporate port towns of the Baltic which had that handy corporate navy with corporate cannon to enforce its idea of open trade.

Renaissance and Elizabethan brewing and drinking in England is particularly interesting as the period ties a lot of later things together…. or founds them… or whatever. For example, Hull was a 1600s brewing town that also was a Hanseatic depot. Hull ale was a contemporary of Northdown as being a premium drink in London in second half of the 1600s. It’s a coastal ale of the sort that governs until the canals reach deeper into the countryside releasing the odd sulfurous and maybe hoppier beers of Burton in Staffordshire upon the national and international market. Like the railways in the mid-1800s Ontario that gave rural Labatt and Carling the opportunity to explode out into the world, England’s canals of the early 1700s also placed brewing at scale nearer the grain fields, likely cutting out middlemen and displacing premium coastal brewing perhaps by undermining existing price. Theory. Working theory.

What was displaced was the model set by the Hanseatic League. Renaissance Hamburg was the greatest brewing center in the history of beer – 42% of the workforce was involved in brewing. The Hanseatic depot at King’s Lynn still stands, one of the branch locations of Hanseatic activity. London was the Kontor with its headquarters of import / export operation located just west of London Bridge on the north shore of the Thames where Cannon Street station now stands. One of the coolest thing is that there have basically been two owners of that site since perhaps 1250 as the vestigial Hanseatic League interests in Lübeck, Bremen and Hamburg sold it to the South-Eastern Railway Company in 1852. The presence of the Hanseatic League cannot be minimized at the critical point in the 1400s. Consider this passage from 1889’s bestseller The Hansa Towns by Helen Zimmern. It has a certain ripe Victorian style but does explain things like this:

Nor was London by any means their only depôt. It was the chief, but they also had factories in York, Hull, Bristol, Norwich, Ipswich, Yarmouth, Boston, and Lynn Regis. Some mention of them is found in Leland’s “Itinerary.” Under an invitation to the Hanseatics to trade with Scotland we find the name honoured in legend and song of William Wallace. In John Lydgate’s poems we also meet with our Hanseatics. In relating the festivities that took place in London city on the occasion of the triumphal entry of Henry VI, who had been crowned king at Paris some months previously, the poet narrates how there rode in procession the Mayor of London clad in red velvet, accompanied by his aldermen 196 and sheriffs dressed in scarlet and fur, followed by the burghers and guilds with their trade ensigns, and finally succeeded by a number of foreigners.

“And for to remember of other alyens,

Fyrst Jenenyes (Genoese) though they were strangers,

Florentynes and Venycyens,

And Easterlings, glad in her maneres,

Conveyed with sergeantes and other officeres,

Estatly horsed, after the maier riding,

Passed the subburbis to mete withe the kyng.”

A love of pomp and outward show was indeed a characteristic of the Hanseatics in England who thus perchance wished to impress upon the natives a sense of their wealth.

Henry IV was crowned the King of England in 1399. Hanseatic League ambassadors are in the procession when he enters London for the first time. They are somebodies. And they are powerful. They had a wee war with England from 1469-74… and won entrenching their right to trade. Hopped beer was not introduced to England by a few straggling sailors showing up at a few coastal towns. It was brought along – even imposed perhaps – by a massive commercial and military complex. Let’s look at some maps at how the Hansa QH has been described:

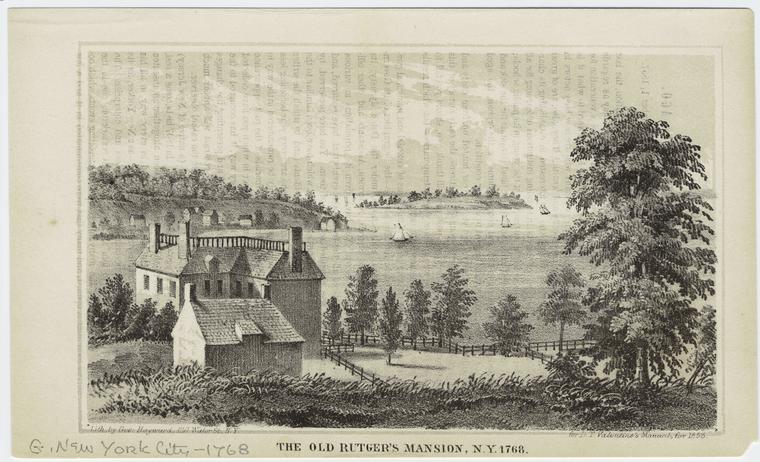

The illustration to the left is a detail of the 1633 reprint of the 1561 Agas map. You can see the location of London’s Hanseatic Steelyard in blue to the west of London Bridge. Above way at the top of the text is a much finer detail of the site. Notice it is referred to as the “Stylyarde.” In the middle is a 1720s map of Elizabethan London. Notice the site is now referred to as the “Stillyard.” And to the right is a diagram of the site of the Steelyard itself in this case called the “Stahlhofes” – as it was in 1667 according to a late 1800s German atlas. So, we have four ways of spelling the name of the site. Which means that each needs to be run through the dark Satanic

research mills if we are going to have an idea of what’s going on. In a note to the discussion of John Stow‘s Survey of London (editions from 1598 to 1603), British History Online has an extended discussion in a footnote on the variously described Stillyard / Steelyard / Stilliard / Stelehouse / Steleyard which states that there was a trade presence from Cologne there as early as 1157. It also indicates that the German version Stahlhof that appears rather early on means a stall hall – a marketplace. Stow himself describes the site and operations at length in his narrative map of London including the following:

Next to this lane, on the east, is the Steelyard, as they term it, a place for merchants of Almaine, that used to bring hither as well wheat, rye, and other grain, as cables, ropes, masts, pitch, tar, flax, hemp, linen cloth, wainscots, wax, steel, and other profitable merchandises.

Interestingly, as Stow notes, past the intervening church, near the Steelyard in Haywharf Lane in the late 1500s there was a “great brew-house” operated in the past by Henry Campion and then by his son Abraham. Life in the district was… lively. In the poem by Isabella Whitney (1548–1573) “The Wyll and Testament of Isabella Whitney” we read the following:

At Stiliarde ſtore of Wines there bée,

your dulled mindes to glad:

And handſome men, that muſt not wed

except they leaue their trade.

They oft ſhal ſéeke for proper Gyrles,

and ſome perhaps ſhall fynde:

That neede compels, or lucre lures

to ſatiſfye their mind.

So, as we see on the image to the right, there is a wine house. I assumed it was a wholesale depot but it appears to be an Elizabethan retail party palace where lads and lassies mingle as they consider drink, lust and lucre. February 1582 government orders issued by the Privy Council to the Lord High Treasurer show the Stillyard being excused from certain taxation – right under another order allowing the export of 1,000 tuns of beer from London. Elizabethan brewing and trading at scale. You don’t hear about that often. Leaping ahead into the next century, Samuel Pepys, diarist and high government official, records a number of visits to the site in the 1660s. On Friday, 13 December 1661 he wrote:

…to the office about some special business, where Sir Williams both were, and from thence with them to the Steelyard, where my Lady Batten and others came to us, and there we drank and had musique and Captain Cox’s company, and he paid all, and so late back again home by coach, and so to bed.

On Monday 26 January 1662/63 he stated that he was “up and by water with Sir W. Batten to White Hall, drinking a glass of wormewood wine at the Stillyard… while on Sunday, 2 September 1666 he uses it as a location in his description of the Great Fire of London. Perhaps most gloriously, he gives us this image of a part of his day on Wednesday, 21 October 1663:

Thence, having my belly full, away on foot to my brother’s, all along Thames Streete, and my belly being full of small beer, I did all alone, for health’s sake, drink half a pint of Rhenish wine at the Still-yard, mixed with beer.

Rhenish mixed with beer. There’s a challenge to today’s sense of yum. Thankfully, he also drank Northdown and Hull so it was not all weird for Sammy. I am going to leave it there but to review, then, what we have seen is that the Hanseatic League was a massive trading partner which had a huge export trade in beer in the 1400s. It had a very significant governmental foothold in the middle of London which was recognized from at least 1399 to the 1660s as something to be reckoned with. The business presence stretched for 700 years from the 1150s to the 1850s. They ran a retail and entertainment hall of some sort exactly when beer is coming into England at the same time that they operate the largest brewing center in the world at Hamburg.

Suffice it to say, there is more to be found about the role of the Hanseatic League and the history of hopped beer in England. Does it support the rough overlapping sequence Haneastic hopped beer (say Hamburg and later Flemish 1300s to 1600s) => coastal hopped beer (like Hull and Northdown, say, late 1400s-1712) => canal based hopped beer (Burton after 1712)? Could be. Need to find out.

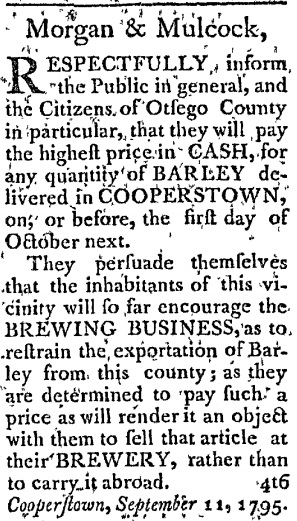

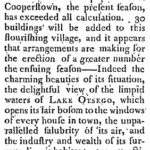

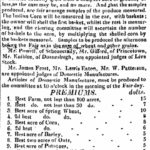

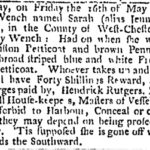

Yet, the future was now. Science was coming to agriculture in upstate New York. Ben Franklin’s dream of advanced husbandry which took a foothold in Philadelphia after the Revolution finally found fertile ground in the race west – even before the Erie Canal. See? The 1820 Duanesburgh fall fair was giving out prizes for the best acre of spring wheat. Twice the prize for the best acre of barley. Then as now – Duanesburgh looked to the future.

Yet, the future was now. Science was coming to agriculture in upstate New York. Ben Franklin’s dream of advanced husbandry which took a foothold in Philadelphia after the Revolution finally found fertile ground in the race west – even before the Erie Canal. See? The 1820 Duanesburgh fall fair was giving out prizes for the best acre of spring wheat. Twice the prize for the best acre of barley. Then as now – Duanesburgh looked to the future.

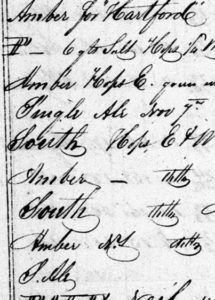

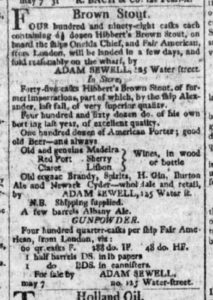

Next, Hibberts Brown Stout. This stuff is all over the place. Click on that thumbnail. That is a notice from just one store in 1805 stating that they have fifty-five casks on hand with another 498 casks on route. British beer brought in and in bulk. Broadly.

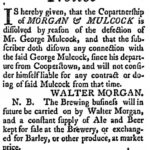

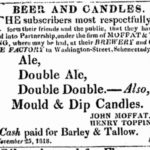

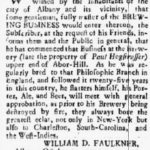

Next, Hibberts Brown Stout. This stuff is all over the place. Click on that thumbnail. That is a notice from just one store in 1805 stating that they have fifty-five casks on hand with another 498 casks on route. British beer brought in and in bulk. Broadly.  Plus, there’s southern beer. You see it in the logs. Click on the ad. Brewing was not practical below a certain latitude so brewers like William Faulkner of NYC and Albany shipped to South Carolina… and the West Indies. He died in 1792. Not to mention there was

Plus, there’s southern beer. You see it in the logs. Click on the ad. Brewing was not practical below a certain latitude so brewers like William Faulkner of NYC and Albany shipped to South Carolina… and the West Indies. He died in 1792. Not to mention there was  And it goes on and on –

And it goes on and on –