So, last October I posted about the location of Rutgers’ 1700s brewery in New York that seems to have ended its days in a fire in the 1780s – and then went off looking at other stuff from the same era related to other families and other breweries. But I got to wondering about when that Rutgers brewery was built and came across a dense essay on the family’s genealogy that just about answered every question I could imagine asking about them. So, once again, I am up at 5:30 am instead of snoozing for another two hours to see if I can get all this out of my head. The essay is located in that best seller from 1886 called The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Volumes 17-18 published, neatly enough, for the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society.

The particular article in that journal is named “The Rutgers Family of New York” and it was written by Ernest H. Crosby. Without getting into the story of the Society itself, it’s interesting to note that the sister of the last wealthy brewing Rutger married into Crosby folk, one of whom, Enoch, was a Revolutionary spy for the unLoyalist side who became the basis for a novel by James Fenimore Cooper. I know this because there is an other article in the same book entitled “Geneological Sketch of the Family of Enoch Crosby” but enough about that. Let’s look at the Rutgers. Some highlights for starters and then, maybe over the weekend, I am going to keep adding more detail as I go along. I know. That’s not professional. It’ll be messy. I hear you. Bear with me.

1. Five generations of the family from the 1640s to 1830 were wealthy brewers who converted their resulting wealth into land ownership and political power.

2. They are slave owners – something not much mentioned with New York. Notice the reference in the lower left of the 1639 Vingboons map of Manhattan to the “Quartier van de Swartz & Comp de Slaven.” Here’s a very searchable reprint from 1670 to play with.

3. Before the Revolution they had at least four separate breweries concurrently being operated by fourth generation siblings and cousins.

4. They also operated two farms in downtown Manhattan that supplied their breweries with their own grain and which were likely worked by slaves.

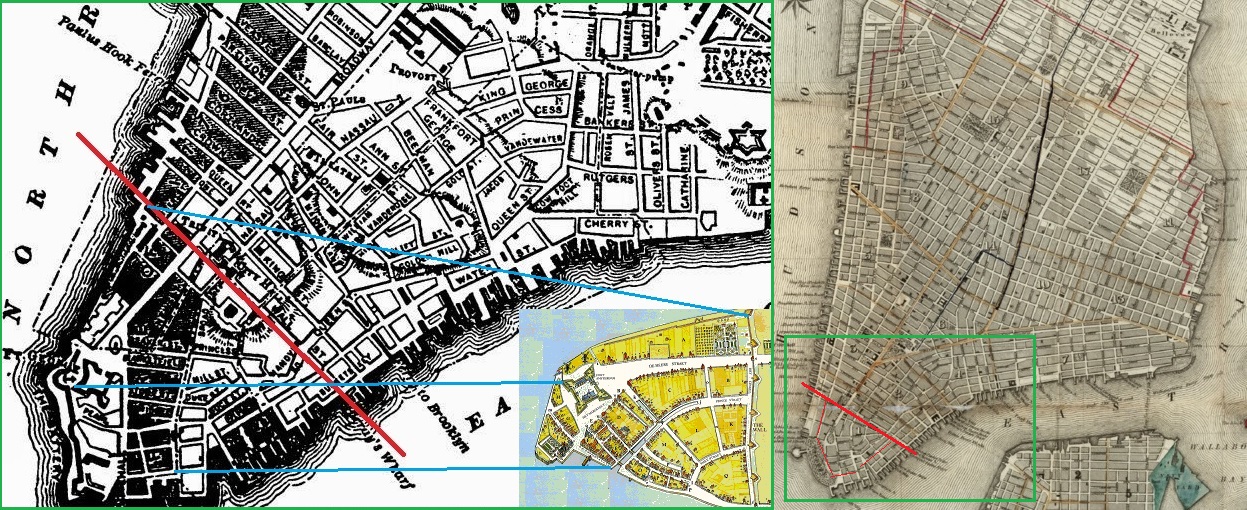

I have seen 18,000 booted around as the figure for the population of New York City around 1760. By 1790, there are over 33,000 residents of the City. By 1830, there are over 202,000 living there. Good to keep those figures in mind as we go through this. Also, keep in mind the ugly diagram from this blog post from last weekend which gives a sense of the urban expansion during those years.

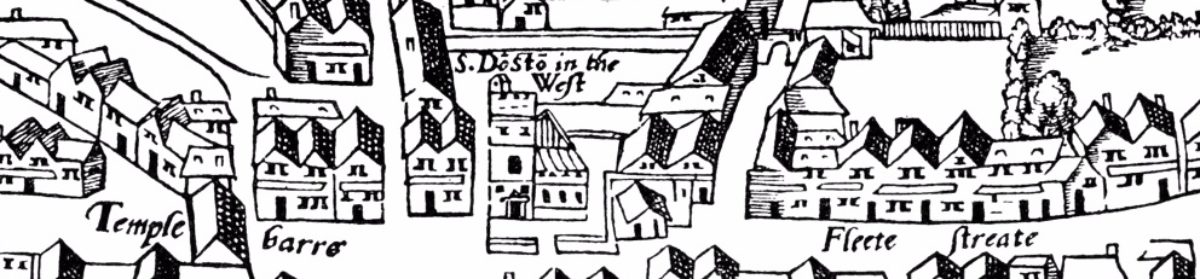

The first brewery operated by the Rutgers dynasty was located on Stone Street in very downtown Manhattan by the second generation’s only male, Harman Rutgers, who moved from Albany in 1693 bringing his sons, Harman and Anthony. The street corner where it was located is still there, Stone Street and Whitehall. Click on the pale coloured thumbnail. The original name for Stone Street in the Dutch era was “Brouwer Straet” or Brewers’ Street. Gregg Smith in Beer in America: The Early Years 1587-1840 identifies this brewery but confuses the location saying it is “located on the north side of Stone Street near Nassau.” Nassau did not extend south of Wall Street at the time. The Rutgers were not the first to brew at the site. They bought an existing brewery operated by the family of the late Isaac de Forest. De Forest had immigrated to the New World with the father of Harman Rutgers (1st) in 1636. It had been operated since the 1650s relied on a well that was apparently still there in 1886. The insanely detailed Costello Plan of New York City from 1660 shows the location as well. Drawn as a bird’s eye view with every building set out, you can clearly see the intersection of Stone Street and Whitehall on this 1916 reprint. Click on the other thumbnail.

The second Rutgers brewery is that of Anthony Rutgers (1st) of the third generation. Located on Maiden Lane, it sits according to the record on the north side of the street on the blog between William and Nassau Street. This is an odd site as it is one block from the better recorded brewery of uncle then cousin Harmen. As you can see, like Stone Street, the location of this brew house on the block between is still there. The block is also shown on the 1730 Bradford map also shown right there on a thumbnail with the “A” showing where this brewery would have been. Not a lot of detail. In a letter dated 6 September 1720 from Isaac Bobin to George Clarke we read:

…As to Albany stale Beer I cant get any in Town, so was obliged to go to Rutgers where I found none Older than Eight Days I was backward in sending such but Riche telling me you wanted Beer for your workmen and did not know what to do without have run the hazard to send two Barrels at £1 16/ the Barrels at 3/ and 6/. Rutgers says it is extraordinary good Beer and yet racking it off into other Barrels would flatten it and make it Drink Dead…

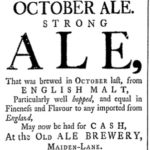

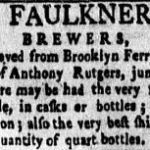

Isaac Bobin was the Private Secretary of Hon. George Clarke, Secretary of the Province of New York. So clearly Rutgers was as good as second to Albany stale for high society… or at least their workers. And in any case – we do not know if it was from Anthony’s brewery or Harman’s. Not a lot of detail. Unfortunately, the 2014 book Manhattan in Maps 1527-2014 states at page 40 that there were basically no maps drawn from 1695 to Bradford’s in 1730-31. Drag. We will have to leave it at that for now for Anthony’s brewery. Except for this irritatingly detailed but undated reference in a letter, the PPS referencing this brewery for someone needing to find a nearby residence, meaning it is a known landmark. Oh – and in the notice in the New York Gazette from 3 July 1769 confirming the brewery was in operation as late as that date. That’s in the thumbnail up there.

Isaac Bobin was the Private Secretary of Hon. George Clarke, Secretary of the Province of New York. So clearly Rutgers was as good as second to Albany stale for high society… or at least their workers. And in any case – we do not know if it was from Anthony’s brewery or Harman’s. Not a lot of detail. Unfortunately, the 2014 book Manhattan in Maps 1527-2014 states at page 40 that there were basically no maps drawn from 1695 to Bradford’s in 1730-31. Drag. We will have to leave it at that for now for Anthony’s brewery. Except for this irritatingly detailed but undated reference in a letter, the PPS referencing this brewery for someone needing to find a nearby residence, meaning it is a known landmark. Oh – and in the notice in the New York Gazette from 3 July 1769 confirming the brewery was in operation as late as that date. That’s in the thumbnail up there.

The third Rutgers brewery is the other one on Maiden Street that I discussed last October. A few more facts. In the book History of the New Netherlands, Province of New York, and State of New York, to the Adoption of the Federal Constitution by William Dunlap, Volume 2 from 1840 at page CLXXV there is this:

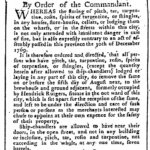

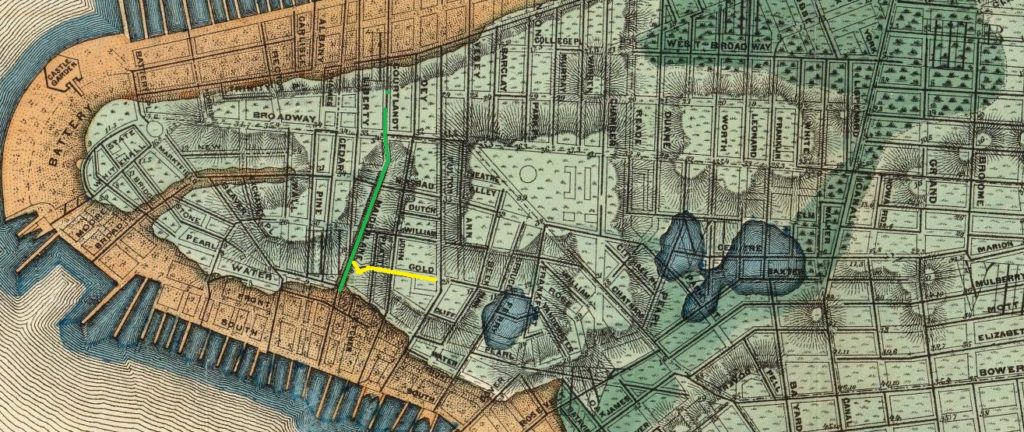

Cart and Horse street is described, as “leading to Rutgers’s brewhouse,” that is, from Maiden Lane to the present John street, and is now part of Gold street. The brewhouse was burnt on the memorable 25th of November, 1783, in the evening of the day the English troops embarked and left the city to Americans.

See, like many anti-Loyalists and others simply wanting to keep their heads down, plenty of New Yorkers fled to safer areas during the Revolution, Albany or Connecticut. So, as we read in this history of the law practice of my fellow Kingsman Alexander Hamilton, the brewery is abandoned in 1776. In the book Generous Enemies, Rutger’s brother-in-law Leonard Lispenard is identified as seeking a way out of the city in the fall of 1775. The brewery is left idle until 1778 when the British co-opt it for local needs and then they destroy it on the way out of town as they dd with many assets in the fall of 1783. The other thumbnail up there is from the British era of brewing, appearing in the Royal American Gazette of 19 April 1781. The burnt brewery is still a landmark in 1787. If you want to learn more about the British cruelty in NYC during the war, get a copy of Forgotten Patriots. Notice also under the thumbnail a detail from the 1730 Carwitham map of NYC in 1730. See how the first block of Gold Street north of Maiden Lane is called “Rutgers Hill.”

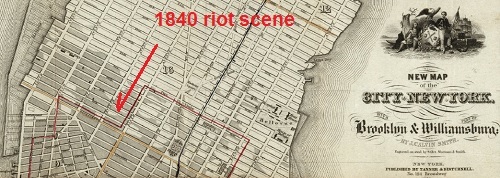

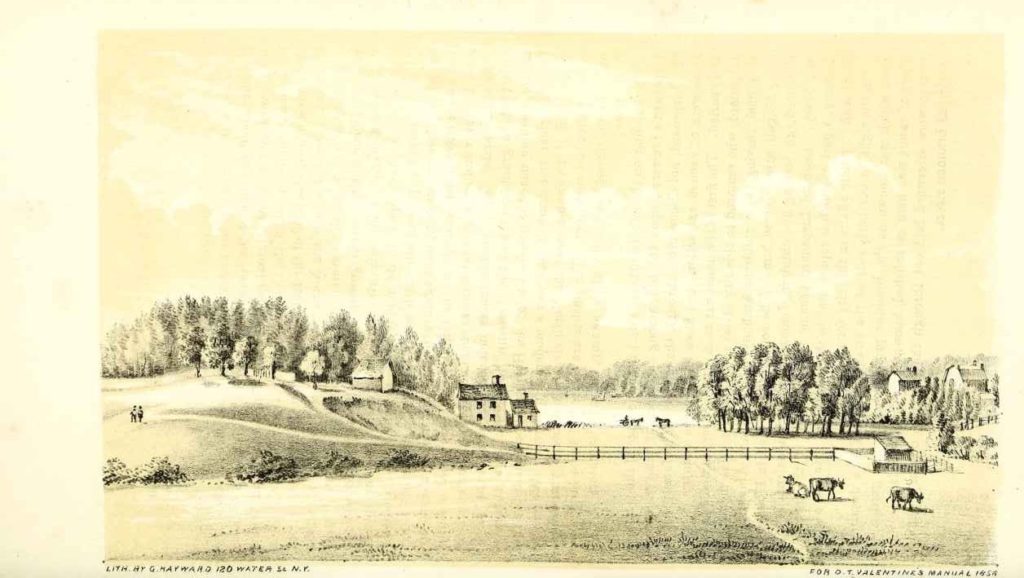

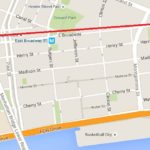

The last two of the breweries were located on country estates, not in the urban core of British New York. The first I will discuss is the one on the East River facing Brooklyn Ferry brewery across the water and to the east of the site of the Catherine Street spruce beer brewery. You can see the thumbnail image of a current map of New York. See the grid of streets outlined in red? That is the Rutgers estate where the last of the men named Rutgers, Henry, lived until 1830 on lands first acquired by his grandfather Harmen (1st) in the 1710s and developed by his father Hendrick. You can see the same lands on the detail of the 1776 Hinton map shown on the next thumbnail. What is now Henry Street, New York is the lane to the family mansion. In The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Volumes 17-18 at page 89 describes the development of the property:

More maps:

The blue green thumbnail is really interesting. It is a detail from the fabulous Viele map of New York and shows the original land mass, the original boggy lands as well as the area of landfill into the East River as of 1865. It also shows the topography. Now notice on the brown thumbnail, a further detail from the 1776 Hinton map, how Rutgers managed the drainage of the bog that extended the farthest inland.

One more thing:

There is a grim, dark aspect to the Rutgers fortunes. The overall system is a vertically integration operation. The estates supply the grain which feed the breweries which create the profits to buy the lands. But the lands were worked by slaves. That large text thumbnail is a notice placed in the 9 June 1760 edition of the New York Mercury. It’s particularly grim when you compare it to this notice in the New York Journal 9 January 1772 about a stray horse. The other thumbnail shows how the brewery was used in the Revolutionary War for the storage of war supplies. The issue of slavery was brought to the forefront in the war.

[More later… it’s now 3:45 pm on Saturday. I wrote the family tree on Thursday after supper.]

[Two and a half weeks later… I am probably going to pick this up in another post… maybe…]

[November 6, 2016: and I did…]

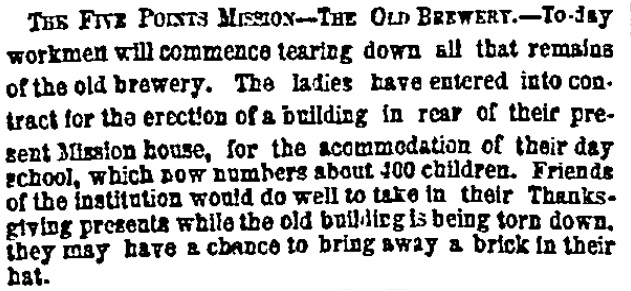

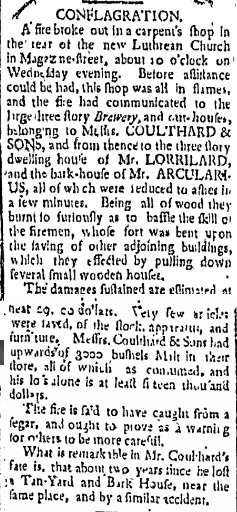

Anyway, the new brewery burned, too. I think they all burned, these old breweries. In the 1 July 1797 edition of Greenleaf’s New York Journal, right, it was reported that all the malt was lost and the whole business was a write off. An errant cigar at the nearby site of the new Lutheran Church apparently started it. He gets up and operating again as by July in 1806, his beers are being

Anyway, the new brewery burned, too. I think they all burned, these old breweries. In the 1 July 1797 edition of Greenleaf’s New York Journal, right, it was reported that all the malt was lost and the whole business was a write off. An errant cigar at the nearby site of the new Lutheran Church apparently started it. He gets up and operating again as by July in 1806, his beers are being