These are busy days. The endy bit of April and the first half of May require my time in the garden. Yesterday I took apart the compost bin, sieved all the good bits out, returned all the half-rotted stuff and layered it with last autumn’s leaves and the parsnip greens from the overwintered crop. And it had gone all anaerobic. Much of it was the consistency of warm chocolate, reeking of sweet bog. Hours it took me. Then there was the week’s laundry. I don’t trust it to just anyone. And another Red Sox game to watch. And tweed to covet.* And supper to make. Saturdays are exhausting. No time to swan and noodle about the the London Metropolitan Archives like some. Research gets little time in spring.Yet, at the back of my mind there is that question. You will recall Sir. Wm Strickland’s observations from 1796 set out in a letter to Thomas Jefferson dated 20 May 1796:

These are busy days. The endy bit of April and the first half of May require my time in the garden. Yesterday I took apart the compost bin, sieved all the good bits out, returned all the half-rotted stuff and layered it with last autumn’s leaves and the parsnip greens from the overwintered crop. And it had gone all anaerobic. Much of it was the consistency of warm chocolate, reeking of sweet bog. Hours it took me. Then there was the week’s laundry. I don’t trust it to just anyone. And another Red Sox game to watch. And tweed to covet.* And supper to make. Saturdays are exhausting. No time to swan and noodle about the the London Metropolitan Archives like some. Research gets little time in spring.Yet, at the back of my mind there is that question. You will recall Sir. Wm Strickland’s observations from 1796 set out in a letter to Thomas Jefferson dated 20 May 1796:

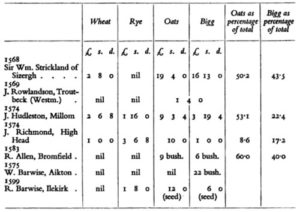

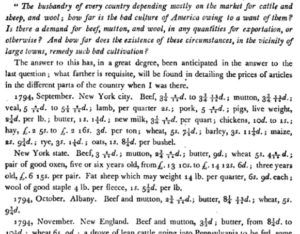

I have reason to believe that a grain of Barley has never yet been sown on the Continent; the grain which is there sown, under that name, is not that from which our malt-liquors are made; it is here known under the name of Bigg, or Bigg-barley, is cultivated only on the Northern Mountains of this Island, and used only for the inferior purposes of feeding pigs or poultry, and is held to be of much too inferior a quality to Make into Malt, and of the five different grains of the species of Barley known to us, it is held to be by far the worst; I have therefore taken the liberty of sending a small quantity of the best species of Barley, (the Flat or Battledore Barley) and the one most likely to succeed with you; this grain is sown in the spring, on any rich cultivated soil; I recommend it strongly to your attention; and shall rejoice if I prove the means of introducing into your country an wholesome and invigorating liquor.

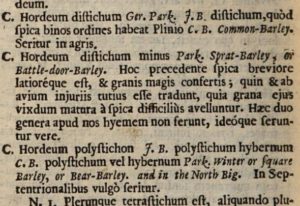

The passage is handy. It fills in two of the five grades of barley known to Britain in the 1790s. Flat or Battledore is the best. Bigg or Bygg is the worst. In the last post about Strickland, we reviewed how that latter lesser sort was six-row, winter or bigg barley. So what were the others? Battledore was a thing of the past in 1866 when the fourth volume of The English Cyclopaedia stated that the Sprat, or Battledore – also called Putney Barley – is the hordeum zeocriton. In a 2010 post, Ron noted that it was also called Goldthorpe. It seems to have hit its peak before the popularization of hordeum distichum or Chevallier. In 1785 it was described in A New System of Husbandry: from many years experience, with tables shewing the expence and profit of each crop by Charles Varlo in this way:

The sprat or battle-dore barley, has only two rows of grain; for which reaƒon , the ear is flat, the corn is ƒhort, plump and thin ƒkinned, not inclined to have a long gross ƒtraw, (but indeed this varies according to the richneƒs of the ground it is ƒown on) it is ƒaid it will grow well on many other ƒorts of land. I have had great crops on tough, ƒtrong, cold clay, or gravel land; but ƒuch muƒt be well pulverised, ƒweetened, enriched, mollified and warmed by tillage.

See, now it’s “Battle-dore” as well. And the focus is not so much scientific in the sense of identifying the plant as it was agricultural in the way the author describes its uses. In 1745‘s Agriculture Improv’d Or the Practice of Husbandry Displayd by William Agric Ellis, it was stated that it will produce “a strong straw that will always grow and stand erect to the last” whereas “common Barley… will fall down, and sometimes rot on the Ground.” Being also an earlier crop, the sprat or Battledore was harvested in 1744 before damaging rains came.

It is this Sort of Barley that is most valued by Distillers, for producing the greatest Quantity of Spirits, and is no less profitable to Brewers, for making a Malt that yields the greatest Length of Worts : The Stalk and Chaff indeed are coarƒish, but the Quality and Quantity of this Grain largely compenƒate for it.

More information is provided in The Natural History of Northamptonshire published in 1715 by John Morton, naturalist and Rector of Oxendon.** He records that there were two sorts of barley in his immediate area: sprat or Battledoor barley and Long-eared barley. Rath-ripe barley, however, was being grown in the area of Lowick, twenty mile to the east, and in fact it was the only barley sown by his colleague the Rev. Mr. Poulton of that parish. Each of these are distinguished, again, from common barley. Reaching back another twenty-nine years, we see the sorts of barley described in 1686‘s The Natural History of Stafford-Shire by Robert Plot – perhaps my favourite new old book of the year given how it may contain a creation myth, the very genesis of Burton and its ales. In one exciting passage at page 347, Plot states:

… it remains only that we recount the varieties of each kind sown here; and by what rules they are guided in the choice of their seed: there being as many sorts used here, and perhaps more, than in some richer Counties. For beside the white-flaxen, and bright red-wheat (which are the ordinary grains of the Country) they now and then sow the Triticum Multiplex or double-eard wheat; Triticum Polonicum or Poland wheat; and Tragopyrum, Buck or French-wheat; all described above Chap. 6. And for barleys; beside the common long-eard, and sprat-barley, which are most used; they sow sometimes the Tritico-speltum or naked barley, of which also above Chap. 6. And amongst the Oats: beside the White, black, and red Cats; at Burton upon Trent I found they also sowed the Avena nuda or naked Oat ; described, Ibidem.

Is anything more fabulous than a text that is 330 years old that uses the proper scientific Latin names of things? It’s all so… science-y. But what does it tell us? What does all of it tell us? Here’s what I see:

1. Battledore or Sprat Barley

2. Long-Eared Barley

3. Naked Barley

4. Rath-ripe Barley

5. Bigg Barley

Are these the five sorts of barley Strickland mentioned in his letter of 1796? I don’t know. There must be a masters thesis or two out there on the topic that would give more clarity. And there is that pesky reference to “common barley” that is a bit of a theme throughout these texts. Suffice it to say for now, then, that there were varieties and perhaps ones which are still sown for non-brewing purposes. More research needed. But, clearly, we can be assured that to the gentleman agriculturalist of 1796 Battledore is the best and was spoken highly of for the previous century. Which makes me suggest that if one is recreating porters of that vintage one ought to be using Battledore malt and not the later improved varieties of 1800s Chevallier or mid-1900s Maris Otter. Shouldn’t one? Certainly one would if one is to brew the earliest Burton, like the lads sipped in 1712.

Update: above you will see a passage from John Ray’s 1677 book Catalogus Plantarum Angliae, Et Insularum Adjacentium: Tum Indigenas, tum in agris passim cultas complectens. In quo praeter Synonyma necessaria, facultates quoque summatim traduntur, una cum Observationibus et Experimentis Novis Medicis et Physicis which describes Battledoor barley as a form of hordeum distichum and not hordeum zeocriton. Hmm… in 1838 it was called hordeum disticho-zeocriton. Hmm…This 2003 bit of botany suggests Spratt was a UK landrace out of which other barley strains developed.

*I am having a wee problem over the last six months. It really started in January 2015 with a windowpane tweed bucket hat bought at Pringle in Glasgow. Then, told at work along with other mid-life males to smarten up the look a bit I’ve, well, gone a bit overboard. I can’t recommend Peter Christian highly enough in such tight spots. Clothes for folk with 37 inch arms like me. Delivery by international $25 courier in about five days. I had no idea that I needed a lavender crew neck cotton sweater. But now I have one. And four new sports coats. And new sorts of socks. God, the HJ socksalone have changed my life…

**Which is just nine mile south of the famous Kibworth examined in BBC’s The Story of England mentioned here and here.

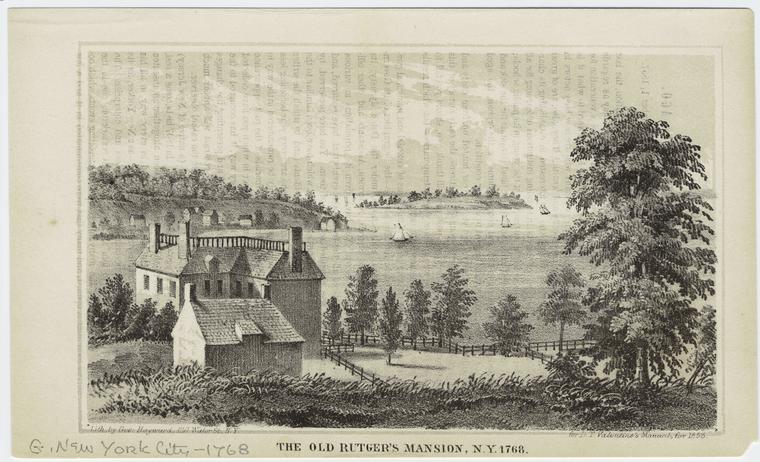

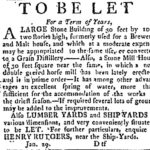

That image up there has little to do directly with this post. It’s from a book entitled

That image up there has little to do directly with this post. It’s from a book entitled

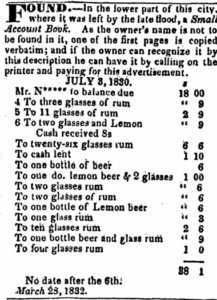

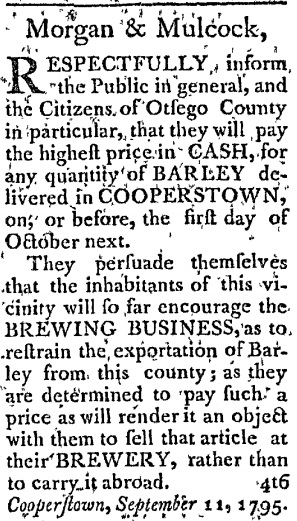

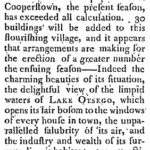

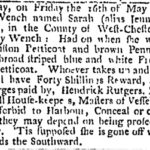

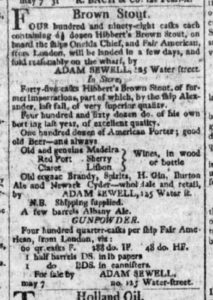

Next, Hibberts Brown Stout. This stuff is all over the place. Click on that thumbnail. That is a notice from just one store in 1805 stating that they have fifty-five casks on hand with another 498 casks on route. British beer brought in and in bulk. Broadly.

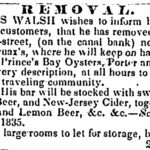

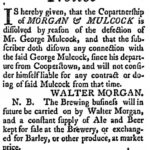

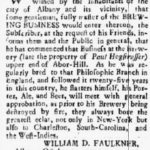

Next, Hibberts Brown Stout. This stuff is all over the place. Click on that thumbnail. That is a notice from just one store in 1805 stating that they have fifty-five casks on hand with another 498 casks on route. British beer brought in and in bulk. Broadly.  Plus, there’s southern beer. You see it in the logs. Click on the ad. Brewing was not practical below a certain latitude so brewers like William Faulkner of NYC and Albany shipped to South Carolina… and the West Indies. He died in 1792. Not to mention there was

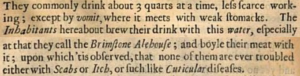

Plus, there’s southern beer. You see it in the logs. Click on the ad. Brewing was not practical below a certain latitude so brewers like William Faulkner of NYC and Albany shipped to South Carolina… and the West Indies. He died in 1792. Not to mention there was  And it goes on and on –

And it goes on and on –