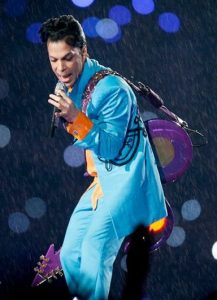

Well, that was quite a something. The game was dull and boring the halftime show was worse. But it’s over. And, really, you only get one “Prince in the rain for your halftime” experience in a lifetime. It’s all degrees of sucking from there. Otherwise, three weeks to March. That’s all I know… so, let’s go crazy with some beery news on a Thursday.

Well, that was quite a something. The game was dull and boring the halftime show was worse. But it’s over. And, really, you only get one “Prince in the rain for your halftime” experience in a lifetime. It’s all degrees of sucking from there. Otherwise, three weeks to March. That’s all I know… so, let’s go crazy with some beery news on a Thursday.

In a surprise move, the beer ads on the Stooper Stupor Super Bowl broadcast actually triggered actual discussion. It started with the odd message from ABInBev summed up neatly with this tweet.

To be clear, Bud Light is not brewed with corn syrup, and Miller Lite and Coors Light are.

Which immediately pissed off big corn. So MillerCoors sent corn farmers their beer! Since then we have been reminded that much high test US craft also relies on corn sugar to boost its strength. This is called chaptalization in wine and it is not considered good. Mainly because it is considered bad. But with US craft beer it is apparently considered – on the near highest authority – to be very good. A rice v. corn debate then broke out. It was exciting. Me, I was caught up in the moment and noted that “138 years of a massively popular rice-based beer and its cultural place still confuses some commentators.” Stan piled on historically and noted with both flair and panache:

On January 30, 1881, well before A-B took aim on beers brewed with corn, the author of a full-page article in the Chicago Daily Tribune chose the side of rice in the rice versus corn debate. The author stated, “Corn beer is not a drink for Americans or Germans. It is good enough for the Spaniards, Greasers, Indians, and the mongrel breeds of South America.” Instead the author lauded the exceptional crisp taste that resulted with rice, and added, “for years the ‘blonde,’ or light colored beers have been fashionable and grown into public favor in America.” The author also suggested most breweries in Chicago used rice, while Milwaukee brewers used corn.

Me, I’m pro-corn since at least 2008. And I am pro–rice, too. And Jeff’s from sugar beet farming stock. So we are all the better for the whole thing.

Changing gears but still on the general theme of “Knowing v. Not Knowing What’s Real” last Saturday England’s newspaper The Telegraph broke the news that no one had considered ever before – that there is a craft beer bubble! To be fair, the article mainly focused on the bubble from an investor’s point of view.

“There is still growth, but the market is now much tougher for new entrants,” says Jonny Forsyth, global drinks analyst at market research group Mintel. “The number of brands is outstripping the growth and now people with money are wising up to the market. If someone asked me to invest in a craft beer company now, I’d say ‘no way, that ship has long sailed.’”

Hard to disagree with that.* And in Colorado, a fourth brewery had announced its closing – the fourth just since 2019 began. Remember: money likes money, not fads. Apparently thermometers are sorta fads… or at least not traditional…. or someone was having a bad day. Speaking of making money, there was an interesting follow up to the news last week of Fuller’s sale. Head Brewer, Georgian Young tweeted:

Thank you @Will_Hawkes it has been a strange week with so many uncertainties for some colleagues but my great team @FullersHenry @FullersHayley @FullersGuy along with the Engineers, Tech services, Quality et al are looking forward to the next chapter friends

Then the former Head Brewer, John Keeling, tweeted: “Today I took people on a Fullers Tour, not sure if there will be many more.” Melancholy days even if the future is arguably… well, hopefully no less as bright.

Attentive readers will remember Robert Gale. He won the 2012 Christmas Beery Photo Contest. Well, Robert is living with Crohns Disease and recently had a stoma – or alternative nether region – installed. He recently tweeted about a post he placed on his blog with this fabulous invitation to readers: “Here’s my experience when I tried beer for the first time since having a new bum installed“! Here is his post entitled “Beer and Stoma.”

Once upon a time, an anonymous brewer berated R(Hate)Beer on this here blog. Now, with the announcement that it has been fully owned by ABInBev, he is not alone. Which is a bit unfair but not entirely unfair. Oddly, the former principle owner wrote on the competing – and for my money superior – BeerAdvocate:

RateBeer is a quality-focused organization, and our value to the community has always depended on our integrity, and willingness to put in greater effort to produce more meaningful scores and information. I’m very grateful for having the opportunity to serve you all. It’s been a great pleasure meeting so many of you in person, and through this more fully understanding our important role in industry, and the joy, pride and responsibility felt by so many out there in RateBeeria.

That’s nice. As I have reminded you all often, always remember there are people out there behind the blogs, forums, tweets and… what else is there? People. And money. People and money. And beer. People and money and beer.

#FlagshipFebruary is one week in and – boy oh boy – are there ever more days in the month than actual flagships out there, aren’t there. We learned that macro brewed Euro-imports are allegedly flagships. We learned that a brewery can have eight flagships. And another can have a sexist flagship. We learned that it’s departure lounge beer, “stupid” and a “legacy craft promotional thing.” It’s cloudy and new, too! We also learned that all the sponsorship were only to make sure the writers chosen to write blog posts got paid. [Ed.: we are just having a personal fugue state experience for a mo… and… we are back.] That’s nice. The upside is that it did not die a dumb death.** And this one won me (even with the “moule frites” for mussels and fries***) by proving this is not just, not solely #OldBeerForOldGuysFebruary. Plus I was reminded how wonderful McAuslan Oatmeal Stout is from a modestly priced can. Fabulous! The downside is we still have no idea what it all really means other than some sort of odd booze-laced homage to the Counter-Reformation. Whatever it is, what it is now won’t likely be what it is a couple of weeks from now. Stay tuned. I’m rooting for it. Really. Like almost 50/50 on the upside. Well, except for money for writers. I’m 100% on that especially given how much money they are getting each!

That is it. Early February ice storm out there as this goes to press. Need to shuffle along not knowing exactly when my feet will be cut out from underneath me. Meantime, look to Boak and Bailey on Saturday and then Stan on Monday for updates on these and many more good beer news stories.

*Some always try.

**An actual phrase in our household: do not die a dumb death. Like the award winner “Doubt it, Ralphie!” which I thought was a line from some forgotten early 1960s TV comedy until Dad told me that when there was a neighbourhood kid who hung around when I was maybe four who just lied all the time. Name? Ralph.

***I just can’t shake the sub-motif of Turgenyev’s Fathers and Sons.

Confession. I have fed Stan in my home. I have been asked by Stan why he bothers discussing things with me. My name appears in this book. I am very fond of Stan. All of which may influence my opinion of his writings, of this book. Along with the fact that this was a review copy kindly forwarded from the publisher. Can’t help it. Heck, if I run the photo contest again this Christmas I might just give it away as the only prize. I’m like that.

Confession. I have fed Stan in my home. I have been asked by Stan why he bothers discussing things with me. My name appears in this book. I am very fond of Stan. All of which may influence my opinion of his writings, of this book. Along with the fact that this was a review copy kindly forwarded from the publisher. Can’t help it. Heck, if I run the photo contest again this Christmas I might just give it away as the only prize. I’m like that.