I rarely think of things as being “Canadian” because “Canadian” is a bit elusive. Usually you need an American friend to let you know something is weird so that you can tell him “oh, that’s Canadian.” Sitting in a beer tent at long plastic covered tables during a cold downpour watching iconic 1970s rockers April Wine on a military base at a civvie invitation only concert feet in chilling puddles watching soldiers and pals and dates and, apparently, parents and grandparents having a good time on the one macro beer on offer struck me as pretty Canadian as I was sitting in the midst of it there last night. There in the foggy tent on the parade square asphalt. Do other nations even have laws requiring beer tents? The stamping of hands as you go in? I didn’t have any beer. Not because I didn’t like the beer. Mooseheads pale ale is decent enough for a beer tent. Fact: the porta potties were a hurricane away. Others didn’t pass on the opportunity. Watched one guy down eight or ten Mooseheads in the first half hour we were there. He was givin’ ‘er. As we say. It was so foggy in the tent from the downpour outside that it started condensing on the inside of the tent, rain reforming to pour on our heads. A science lesson in itself. We left not just because of that or because it was so loud that I stuffed wads of Kleenex in my ears but because they played their 1979 cover of King Crimson’s “21st Century Schizoid Man” which I had not appreciated they had in fact once recorded. They did an excellent job for the eleven minutes of that tune but the crowd was there for songs on the radio, songs with lyrics like “tonight is a wonderful night to fall in love, oh yeah” and not covers of early prog rock speed metal. Earlier, folk had happily Legion danced to the opening band, Whiskey Overdrive, playing classic rock covers. Legion dancing requires a generous application of the elbows. And a few Mooseheads. There’s a real happy levelling that goes on when military folk are partying. The opposite of the oneupsmanship you can get at house parties filled with strangers. Military folk already know who in the room is one up. Still, there was a bit of a crush at the exit gate as we left. But plenty stayed. It was really good. Good company. Good out dinner before. Good being among Canadians. People were having a time.

It’d Be Nice To Get More Actual Spruce Beer Brewed

Because good beer is (i) a pleasure trade topic and (ii) a minor league one in the hierarchy of pop culture, you do have to accept this sort of thing:

Spruce ice cream, spruce syrup and spruce-tip salads were hot culinary items this spring, but creating tasty treats with the needles of this northern evergreen is far from a new notion. Spruce-beer soda has been a favourite among French-Canadians for decades. Its popularity has wavered over the years, but people are once again clamouring for the sweet, earthy drink. First Nations and early settlers of Quebec brewed vitamin-C-filled spruce beer prior to the 1700s to combat kidney illnesses, stomach upset and scurvy. It was considered a poor man’s drink until Swedish explorer Pehr Kalm brought news to Europe that the strange recipe was indeed making people healthier.

And the article is really about the use of spruce as a flavouring so there’s no need to go all handbags or anything. But it is a shame that no one is brewing actual 1700s spruce beer. As longer term readers would be aware, the recipe from 1759 is there for all to see and brew. George Washington brewed one when he was still sensibly loyal to the Crown in 1757. The heavy sweetness of molasses offsetting the pungent household cleaner effect of the spruce boughs. Pretty sure, however, Kalm didn’t teach the Swedes anything about evergreens. We had a Swedish exchange student who showed us all on the walk home in spring how to eat the new mild softwood buds just as the brown paper coating was cracking. Can’t imagine Vikings didn’t know that, too. The English in Hudson Bay as early as the 1660s and ’70s knew about the anti-scurvy properties of beer, something Billy Baffin seemed to be figuring out in 1610-11 as he rammed herbs into it. Something we have learned Champlain had to work out on the fly about the same time in New France.

OK. Let’s agree that it was pervasive and useful. Maybe oddly, there seems to have been a taste for it well after the frontier days and the retreat of scurvy. Craig located spruce beer still being brewed in Albany in 1790. I found it being spruce used in something called California Pop Beer in the third-quarter of the 1800s in New Jersey. And as the article says, it used to be in the Crush soda pop line up deep into the 1900s. But by the late 1800s it’s one of the forms of adulteration in beer listed in at least one British study. Was that it’s fate? Science considered it bad for beer?

Spruce is clearly an eastern North American indigenous beer flavouring that was enjoyed for centuries. BeerAdvocate lists a scant few spruce beers. I’ve had the one from Garrison in Halifax, Nova Scotia as well as its cousin, Alba from Scotland. It’s be nice to have more – and, really, have ones that are molasses based old school ales. Are there other beers like this? Beers built around local ingredients and adjuncts that were quite broadly commercially popular which have fallen so far out of favour that even the craft brewers won’t touch them? The gruits I suppose if you go far back enough, keeping in mind that gruits are specific early Renaissance tax regime imposed herb blend beers from the Low Countries and not just any old herb beer from any old point in European history. Calling any old herb beer gruit is like calling something pumpkin ale when it’s sold in July and is just flavoured with pie spices and gourd gak from a can.

Need to start CAMSA to go alone with CAMWA and CAMMA. Spruce Buds perhaps?

#22 – Halfway Home

The new Nanos numbers this morning were not good. Another small slide. When he had called a friend’s office later he hadn’t been in yet. The voice on the phone had used the words “death march” even with weeks to go. Weeks to go this time could mean weeks to go of this. Or, worse, an “anyone but the NDP” move to the Grits leaving us in the wilderness. Again. It had stung hard to have to listen to Elsie Wayne so often.

Limited upside. Great. And the boss let the message out that he’s not perfect. What an interview with Joe Rockhead the other night! I am who I am and that’s who I am. People want a Syrian grannie in every church… for God’s sake. Somewhere they know they can drop off Timbits or a casserole or a blanket or something to feel good about themselves. Why is that too much to ask?

David Shrigley’s “My Beer”

I love it. While “beer communicators” are off being told what to write by brewery publicists who can’t believe their luck, “My Beer” an expression about beer. It’s about what the one drinker thinks – or perhaps might think – if he or she thought about beer. The film is an animation of Shrigley’s piece by the same name from his 2004 book Let’s Wrestle.

Your Vital Links To Beer News For Wednesday Half-Day

Two days back off holiday and I am already taking an afternoon off. Slacker. Well, there was a need to do so but not really to do anything other than mind the wee one. Fortunately there’s afternoon baseball to watch online and lots of beer news to catch up with.

Two days back off holiday and I am already taking an afternoon off. Slacker. Well, there was a need to do so but not really to do anything other than mind the wee one. Fortunately there’s afternoon baseball to watch online and lots of beer news to catch up with.

=> First, the best news of all is that I may have figured out a cure to the spam war. When I was in Maine I opened up the comments page on the admin to find myself facing over 5,000 pending comments needing manual deleting. I rolled up my sleeves and figured out a few new things. Result: no evil bad comments for a few days now. Even though the blog’s FB page has neatly stepped in, I can now state with confidence that the comments will be open… as long as this keeps working.

=> Jordan made an excellent point in passing over of FB which needs repeating: “I hope they take about ten percent market share. They will then be eligible for beer store ownership. That’ll put the cat amongst the pigeons.” He’s talking about SABMiller’s enthusiastic return to the Ontario beer market. While I remain unmoved, the petite reform MOU does state that “ownership of TBS will be open to all brewers with facilities in Ontario.” Get it on, SABMiller. Get it on.

=> I was not able to get my butt back down to Albany after driving through the last two weekends coming and going from Maine. Sad as one of the great leaps forward was held yesterday as the BBC programme “Great American Railway Journeys” was in town filming and included the Albany Ale Project as part of the story of its New York episode. As you can see, Craig aka “Showtime” had as natty a sports jacket as host Michael Portillo. Plus I got an email that read “I have spoken to my Director, Tom, and he doesn’t plan on you being on screen on screen on this occasion..” I should have known partnering with a former hand model would end up like this…

=> Another excellent edition of the “Drinker’s Digest” appeared over at Stonch’s place triggering a rather zesty discussion beginning with: “Tandleman has a point there will be certain people with vested interests who won’t be happy to hear it…” Tandy carried forth himself today. Which is associated with this comment on food blogging’s latest ethical crisis by a noted wine writer. As I mentioned in the alternative format, with all due respect, it isn’t at all just about disclosing receipt of resources and benefit as part of one’s writing. That’s just the entry point for the discussion unless you don’t care or don’t understand how it appears to reasonable people when writers accept resources for what they write from the subject matter of the writing.

=> Maureen speaks for me in relation to 80% of the beer books put out in the last five years: “Routson’s beer primer is no better and no worse than 50 others I’ve read in recent years. The usual suspects parade the pages: beer styles, brewing process, cooking with beer, pairing food and beer, “science-y numbers” with which to impress your pals, and tasting notes aplenty.” Personally, I would have used the line a bit ago when we were all supposed to care which beer went with the chilled shrimp and avacado wrap. Note: Jeff gets special dispensation as his book sat with the publisher for two years for some unknown reason. But we can stop with the identa-texts now, right? Write only original beer books starting… NOW!

That’ll do for now. It’s summer. There’s baseball to watch. And a new beer to try. Not telling which. I paid for it myself. No need to tell you anything about it. Bet it will be great. Not telling why.

Maine Cottage. August. Nap time.

Who Was Joseph Coppinger, Early 1800s US Beer Geek?

The trouble with finding an old text in isolation like the one I wrote about yesterday is establishing some context. Without it, you are at the whim of the person’s claim to fame as opposed to his or her place. It’s as true today as it was in 1815 when Joseph Coppinger published his book on brewing. The context is totally dissimilar. Right now we are still in the era when folk can assert craft beer expertise, isolated from critical assessment due to the flux. We have to take comfort and grounding in the knowledge that few are. In the years leading up to 1815, America was similarly in a time uncertainty. The British were not yet allies again and the lands beyond the east coast’s highlands were not secured. Drifters abounded. I was thinking about this when I was thinking today about Coppinger. How the heck do I know he didn’t make up all that in his book? How can we establish he is reliable? So, I looked to see what I could find out about him. Fortunately, he liked to write letters to the famous and left a bit of a trail:

The trouble with finding an old text in isolation like the one I wrote about yesterday is establishing some context. Without it, you are at the whim of the person’s claim to fame as opposed to his or her place. It’s as true today as it was in 1815 when Joseph Coppinger published his book on brewing. The context is totally dissimilar. Right now we are still in the era when folk can assert craft beer expertise, isolated from critical assessment due to the flux. We have to take comfort and grounding in the knowledge that few are. In the years leading up to 1815, America was similarly in a time uncertainty. The British were not yet allies again and the lands beyond the east coast’s highlands were not secured. Drifters abounded. I was thinking about this when I was thinking today about Coppinger. How the heck do I know he didn’t make up all that in his book? How can we establish he is reliable? So, I looked to see what I could find out about him. Fortunately, he liked to write letters to the famous and left a bit of a trail:

1800: claims in his 1810 letter to President Madison that, prior to emigrating from Ireland to the US, he published a paper in the reports of the Bath and West of England Society on an improved method of the drying of malt.

1802: Coppinger writes two letters to President Thomas Jefferson. He wrote from New York on the subject of naturalization and the need for him to become a citizen to patent an invention. He is an Irish Catholic recently arrived in the New World;

1802-04: Coppinger appears in Pittsburgh on the frontier partnering in a brewery operation located in and even made out of the former Fort Pitt known as Point Brewery;

1806: Coppinger enters into partnership to establish a brewery in Jessamine County, Kentucky. It never comes into operation and a law suit is begun. The dispute is settled through the intervention of the Rev. Stephen Theodore Badin, the first Roman Catholic priest ordained in the United States;

1807: Coppinger wrote from St. Louis a letter to Benjamin Rush, Revolutionary leader. Rush is a pre-Revolutionary anti-slavery activist and a medical doctor. The letter is not about beer so much as a scheme to use public resources to help raise employment levels;

1810: Coppinger wrote to President James Madison describing a list of inventions and also proposes the establishment of a national brewery at Washington. His inventions include an improved threshing machine and a better method of distilling. He gives his address as No 6, Cheapside Street, New York. Says he has been in the brewing trade for twenty years;

1813: An advertisement for Coppinger’s book is published in a Philadelphia newspaper, the Aurora General Advertiser; and

1815: Coppinger writes to former President Thomas Jefferson. He gives his address as 198 Duane St., New York. Jefferson wrote back a couple of week later quite interested in Coppinger’s ideas, noting “in my family brewing I have used wheat as we do not raise barley”.

1815: Coppinger’s publishers, Van Winkle and Wiley of New York, are quite respectable and at the leading edge of the first wave of homegrown American literature. In this same year they publish An Introductory Discourse delivered before the Literary and Philosophical Society of New York, on the fourth of May, 1814 by De Witt Clinton, then Mayor of New York, later state Governor. It is a treatise on the improvement of society.

A brief biography of Coppinger appears in the footnotes to this letter to Jefferson. In his later years he writes two more books: 1817’s Catholic Doctrines and Catholic Principles Explainedand in 1819 On the Construction of Flat Roofed Buildings, Whether of Stone, Brick, or Wood, and the Mode of Rendering Them Fire Proof. He passes away around 1825 after 23 years in the young United States of America. He looks good if a wee bit intense. But, then again, he is a participant in the making of the country, making the world anew. Does this mean he is to be trusted in his description of how to make Dorchester Ale? Not at all. But he has a very good chance of being trustworthy with a bit more digging.

Dorchester Ale: Esteemed When The Management Is Judicious

Fabulous. I think my new best friend is Joseph Coppinger. Sure he published his book The American Practical Brewer and Tanner 200 years ago… but so few people come by these days I don’t care to notice such things. Like Velky Al did a couple of years ago, I came across an online copy of the book as I was looking for something entirely different. [No. No, not that.] And when I did I immediately – well, right after checking out the tanning section – noticed there were a number of recipes for beers. Styles of beers even. A listing of styles. In a two hundred year old book about beer. Odd. I thought that was invented in the 1970s by that Jack Michaelson chap. But, more importantly, he included this:

Fabulous. I think my new best friend is Joseph Coppinger. Sure he published his book The American Practical Brewer and Tanner 200 years ago… but so few people come by these days I don’t care to notice such things. Like Velky Al did a couple of years ago, I came across an online copy of the book as I was looking for something entirely different. [No. No, not that.] And when I did I immediately – well, right after checking out the tanning section – noticed there were a number of recipes for beers. Styles of beers even. A listing of styles. In a two hundred year old book about beer. Odd. I thought that was invented in the 1970s by that Jack Michaelson chap. But, more importantly, he included this:

Dorchester Ale

This quality of ale is by many esteemed the best in England, when the materials are good, and the management judicious.

54 Bushels of the best Pale Malt.

50 lb. of the best Hops.

1 lb. of Ginger.

¼ of a lb. of Cinnamon, pounded.

Cleansed 14 Barrels, reserving enough for filling….This mode of brewing appears to be peculiarly adapted for shipping to warm climates; the fermentation being slowly and coolly conducted: it is also well calculated for bottling.

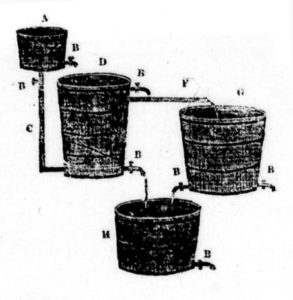

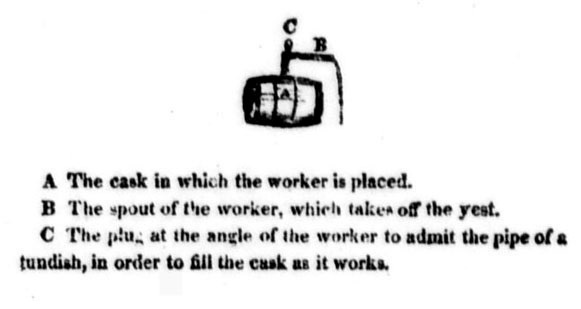

Yes, there is more. I just used those three dots to keep you focused. He goes on and on in fact. Over thirty sorts of beer and a few diagrams like the one above. A few things. First, it’s a description of how to make Dorchester Ale. The careful – or perhaps the caring – amongst you will recall that two years ago while waiting for Craig in Albany to go for a beer, I wandered into the New York State Library HQ and found a large number of mid-1700s newspaper notices for British ale coming into the new world. And a few of those ads referenced Dorchester ale. So there you have it. Dorchester was a top quality ale with a bit of ginger added. Sounds like quite nice stuff. Second, yes, the book was published in 1815. And it was published in that year by the firm of Van Winkle and Wiley located at No.3 on Wall Street. It is a guide aimed at the trade. Aimed at the trade that wants to know about shipping to the warmer climes. Which means exporting ale from New York state. Two hundred years ago. Third, he goes on. And on. The book has a lot of data. I need to get into it to find out what.

I believe this illustrates a point: the problem with records. Believing you know what things were once like based on the available records is a dodgy game. Things like (i) Gansevoort’s adin 1794 asking for barley for ale as the old state in the young nation was coming out out famine leading one to leap to (ii) a prosperous local brewery to the south in 1808 connecting you to (iii) this guide in 1815’s NYC on how to brew for export (iv) all might lead you to understanding that there was in fact a vibrant but little understood brewing trade waaay before the US Civil War and waaay before the advent of lager’s supremacy. But you have to watch that sort of thing. Because records are dodgy things. But at least we may well know what Dorcester ale was. Maybe. Sadly, no reference to Taunton. Maybe. Probably out of style by then in the New York market. That might be it. Maybe.

Massachusetts: Spencer, St. Joseph’s Abbey

Long time reader Brian was good enough to deliver this to me after having driven west for the 1780 Challenge back in May. The beer is brewed by the monastic community at Spencer, Massachusetts. Fortunately, they are a fairly prudent bunch as their beer comes in at just 6.5%. Every time I read some git saying big bottles are for sharing I think of this strength of beer. Mine.

Long time reader Brian was good enough to deliver this to me after having driven west for the 1780 Challenge back in May. The beer is brewed by the monastic community at Spencer, Massachusetts. Fortunately, they are a fairly prudent bunch as their beer comes in at just 6.5%. Every time I read some git saying big bottles are for sharing I think of this strength of beer. Mine.

The burnished gold ale sits under fine lace leaving egg white foam. Shoving the nose deep into the glass, there are aromas of burlap, dry twiggy herbs with pear and banana. A bit of sheddiness but very pleasantly so. The monks suggest there is a light hop bitterness. They are fibbing. On its trip by the gums, there’s plenty of bitter herb as well as a bit of menthol lingering at the end. More of the musty burlap. Underneath the pale malt is sweet and creamy but definitely playing a supporting role. A lightness shows up mid-mouth. There is a little smoke amongst the herbs making me think that this would go great with bacon and old cheddar. But, then again, so does life. There is even a wee bite that reminds me of those saisons which an edge from a bit of white pepper. Clove or very bitter orange maybe. I opened a bag of snapea crisps, the sort of snack monks may have sworn off. It works.

The BA bros rank it lower than the general BAer masses. I get their observation that “nothing really pops out to wow our palates” but I am not sure that’s always the reasonable expectation. This is one of the best beers of its sort that I have had, the flavours articulately placed. But it is not a show off. Instead, it shows restraint and balance. It shows thought. Thank God for that.

Beautica Club… Beautility Beer…

Ah, Utica Club. Craig brought Utica Club. He brought a few other beers. Beers that even came in caged cork topped bottles. But he brought Utica Club. It’s a funny beer. An old school macro lager made by a regional craft brewery. Is it hidden craft? Faux macro? Whatever it is, it’s five bucks for three litres at central NY gas stations. Summertime beer. Maybe even a cure for the summertime blues. Maybe. We talked over a pint or two before turning to a few more complex beers. Sweetish with a well placed jagged edge. Everything in its proper place. Nothing off or awkward. A beer for craft’s endtimes. Both pure and XX. According to the label. We talked of these endtimes. I blame Boak and Bailey, writing that non-derivative book that no one else will match. Takes the wind from the sails, didn’t it. So much for no one ever going beyond what’s gone before, been done before. Things get confused once those sorts of things get going. Not knowing your place. Can’t tell heterodox from orthodox. Hard to find which side of the map is up. Things go round and round. The saison driving north from Virginia or the Carolinas was wonderful after the cork popped. But so many are in a similar way, aren’t they.

Ah, Utica Club. Craig brought Utica Club. He brought a few other beers. Beers that even came in caged cork topped bottles. But he brought Utica Club. It’s a funny beer. An old school macro lager made by a regional craft brewery. Is it hidden craft? Faux macro? Whatever it is, it’s five bucks for three litres at central NY gas stations. Summertime beer. Maybe even a cure for the summertime blues. Maybe. We talked over a pint or two before turning to a few more complex beers. Sweetish with a well placed jagged edge. Everything in its proper place. Nothing off or awkward. A beer for craft’s endtimes. Both pure and XX. According to the label. We talked of these endtimes. I blame Boak and Bailey, writing that non-derivative book that no one else will match. Takes the wind from the sails, didn’t it. So much for no one ever going beyond what’s gone before, been done before. Things get confused once those sorts of things get going. Not knowing your place. Can’t tell heterodox from orthodox. Hard to find which side of the map is up. Things go round and round. The saison driving north from Virginia or the Carolinas was wonderful after the cork popped. But so many are in a similar way, aren’t they.