The title of the patent from 1832 is titillating: “US Patent: 6,894X – Restoring sour or musty beer or ale to its original purity by rebrewing.” Sadly the note at the DATAPM data base tells the rest of the story:

The title of the patent from 1832 is titillating: “US Patent: 6,894X – Restoring sour or musty beer or ale to its original purity by rebrewing.” Sadly the note at the DATAPM data base tells the rest of the story:

Most of the patents prior to 1836 were lost in the Dec. 1836 fire. Only about 2,000 of the almost 10,000 documents were recovered. Little is known about this patent. There are no patent drawings available. This patent is in the database for reference only.

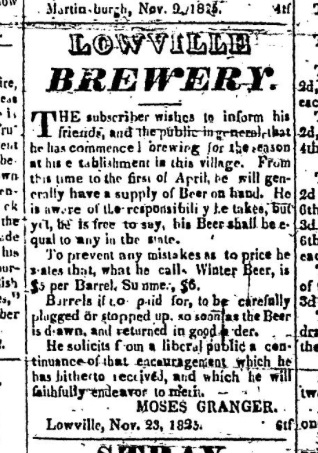

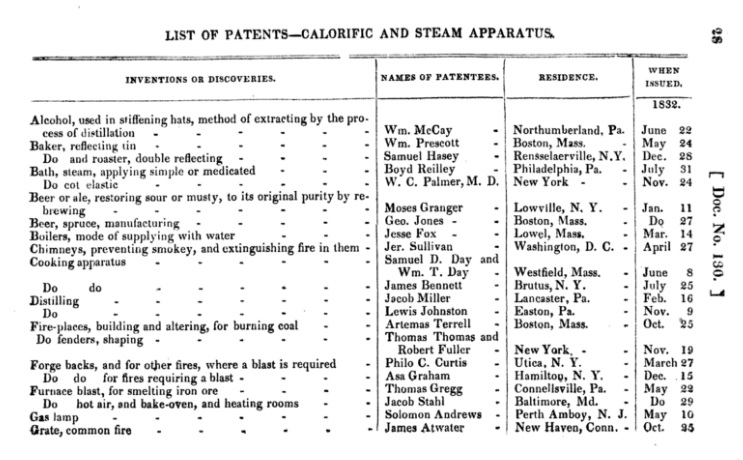

This is sad for us now as well as sad for the inventor, Moses Granger. As you can see above, he started his brewery in Lowville, New York seven or so years before registering his mysterious patent for improving bad beer. The announcement is from the Black River Gazette of 14 December 1825. You can see below from page 28 of the Congressional Series of United States Public Documents, Volume 235 that his patent was issued on 11 January 1832 which means he had to have invented it and then worked on the patent application sometime before that. Notice also that his patent is in a list of “Calorific and Steam Apparatus” which again is a reminder that Steam Beer is a reference to the general introduction of steam powered motors into the brewing trade and not something about the beer itself.

Unlike most of you, I have visited Lowville, New York. It is just about an hour and 45 minutes drive to my south east sitting in Lewis County, the next NY state county to Jefferson which I can see out my office window. It is the home of Lloyd’s of Lowville. My 2005 post on neighbouring Denmark, NY on the hill north of Lowville gives you a sense of the area. Rural limestone Federalist buildings, analogous to our larger urban and military Georgian ones.

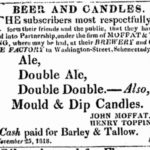

Gary mentioned Moses Granger and this patent in the latest of his further explorations of the odd later 1800s eastern US use of “musty” as a positive term for a class of ale. The patent from an earlier point in time, however, is clearly about the correction of poor beer – restoring it by rebrewing sayeth the patent’s title. “Rebrewing” is an interesting word. In 1818, another two hours modern travel to the southeast in Schenectady, there was rebrewing going on – the last reference I have found to the ancient and famed double double immortalized by Shakespeare. Beer made by reusing beer as sparge water, ramming more power into the wort. It makes a brain smackingly strong drink.

Gary mentioned Moses Granger and this patent in the latest of his further explorations of the odd later 1800s eastern US use of “musty” as a positive term for a class of ale. The patent from an earlier point in time, however, is clearly about the correction of poor beer – restoring it by rebrewing sayeth the patent’s title. “Rebrewing” is an interesting word. In 1818, another two hours modern travel to the southeast in Schenectady, there was rebrewing going on – the last reference I have found to the ancient and famed double double immortalized by Shakespeare. Beer made by reusing beer as sparge water, ramming more power into the wort. It makes a brain smackingly strong drink.

Lewis County, NY in 1825 was still the frontier. See those military installations in my dear old British fort town? Kept back interest in settling NNY as the Erie Canal was opening up WNY. It was settled by the generation after the Revolutionary one, as places like Cooperstown and then CNY started filling up and interests became fixed. Spafford described the place in his 1813 Gazette – and he can be trusted as he was born there. One might read the notice posted by Moses Granger in 1825 that he was the first brewer in Lowville. Spafford shows (at page 50 and 51) that in 1813 there were no brewers in Lewis Co. compared to seven distillers. Jefferson Co. had a ratio of two brewers to sixteen distillers. In 1828, Watertown, Jefferson Co. only had one brewery. The area was awash in rot gut whisky. A rebrewed super strength brewing process might well be worth protecting by way of patent.

I will dig a bit more and maybe post more – and wait for Gerry… again… to correct and add to the story. An excellent thing, too, as by collaboratively assembling what we know the history unfolds. The strange thing is why one would invent such a thing in a frontier setting and then seek the protection of the law – on the one hand just thirty years removed from that log house brewery in Geneva, NY but, on the other, in the era of the scientific brewing of Vassar. An era of great change.

Another interesting post, Alan. I love these old brewing process “patents.” Many were put forward that were rejected because they were mostly just a re-hashing of the usual brewing process with a slight tweak. Most that were successful generally had some form of alternative equipment included, and usually those ones had the actual process part denied. As you noted, re-mashing new beer with old was a long-known process — and one that was much looked down upon when we get into the realm of scientific brewing later in the century. At that point, re-using old beer for mashing was definitely seen as a bad thing, and you only find it recommended for brewers brewing with poorly modified malt. In those cases, it was used to bring the beer up to regular strength, not to make “double” (or double double) strength beer as in the past.

But, back to Granger. Your mention that Granger’s patent was listed for a Calorific and Steam Apparatus” might bear out the notion that his process included new equipment, except that in other places Granger’s patent is noted in the category of “chemical processes.” So, I went and did some digging in my “binders” and this is what I found (sorry your blog won’t let me paste in the image). This comes from the Journal of Franklin Institute, Vol X (14 in the new series), 1832, p. 31:

“Patent grated to Moses Granger, Louisville, Louis County, New York, for a mode of restoring sour, stale, or musty Ale, Beer, or Porter to their original flavour and purity, by the operation of re-brewing.

–Dated January 11, 1832.

A mash is to be prepared in the usual way, and the wort drawn off from it. To the malt-grains which remain, the sour ale, or beer, is to be added, say to the amount of sixty gallons to forty bushels of grains, and drawn off. This liquor is to be boiled with hops, in the proportion of half a pound to a barrel, after which it is to be put into a clean vessel, and kept for mashing at a subsequent brewing, which, we are told, will restore the liquor to is former state of sweetness and purity . –”

So, nothing new under the sun in this one. I was hoping for some cool (yet likely useless) new machine. Clearly in this instance “musty” is definitely seen as old and off, and not the apparently desirable “musty ale” of Hume.

There are plenty of references of brewers using and selling old and sour beer in New York State from before Granger right up through the 1870s and a lot of different remedies – from chalk dust and bicarbonate of soda to sugar and salt to re-processing with hops or finings – to refresh it. In the 1850s and 1860s you see a trend in New York (particularly in the City) for selling “old ale” – from 4 to 12 years old – at Christmas time. It would be hard to argue that that stuff wasn’t “musty,” but it wasn’t Hume musty or Granger musty.

Ah, so it is like small beer in a way. Take the partially spent malt and make a second running from it. Not so much “double double” as “single single” – and not nearly as attractive.

As always, thanks!

Well, maybe more of a single and a half. Presumably the sour beer still had some alcohol and was probably well-hopped to start with. So adding sugars by sparging the grains and then boiling and re-hopping, and then using this to brew a new batch of beer would probably give a stronger beer than usual. Part of the problem with the re-mashing with either blue wort or old beer is that is always noted as being likely to cause problems — ropiness, off-flavors, that sort of thing. I’m not sure why they granted him a patent for this, but it probably didn’t make very good beer. Lipstick on a sour-pussed old hog, really.

That’s the thing. Sour beer isn’t any weaker in terms of alcohol. The boil would drive off some but I don’t expect they are aging it or anything. They are taking a surplus product (spoiled beer) and another surplus product (third sparge grain) and making another sellable product – crappy but maybe stronger beer. But it is largely profit in a marginal market. What I don’t get is there isn’t an invention, just a technique. What would the patent have related to?

That’s why I was curious as to how he got a patent. As I said, most people that got patents included some new gizmo in the process, and it was the new technology that got the patent while any claim on regular processes were denied. Granger doesn’t even add any new wacky ingredients. When William Juby Coleman got his sour-beer restoration patent in England in the 1860s he could at least claim a new proportion of ingredients in his additive — even if the ingredients themselves wern’t anything new. With Granger, the only differences seen to be: 1) proportion of beer to mash; 2) reboiling with a hop addition; and, 3, maybe brewing with sour beer to restore it rather than to “double” strength. Don’t see how that gets a patent.