It’s Session time again. Or it was Friday and now it’s Sunday 8:02 am. See, there’s things to do. Gardening, smoking pork, napping, sitting. So, it was with deep regret that I realized I needed to post something for this the three quarter-ish of a century edition of these, Les Sessions. The question this month is a bit, err, specific:

It’s Session time again. Or it was Friday and now it’s Sunday 8:02 am. See, there’s things to do. Gardening, smoking pork, napping, sitting. So, it was with deep regret that I realized I needed to post something for this the three quarter-ish of a century edition of these, Les Sessions. The question this month is a bit, err, specific:

Creating a commercial brewery consists of much more than making great beer, of course. It requires meticulous planning, careful study and a whole different set of skills from brewing beer. And even then, the best plan can still be torpedoed by unexpected obstacles. Making beer is the easy part, building a successful business is hard. In this Session, I’d like to invite comments and observations from bloggers and others who have first-hand knowledge of the complexities and pitfalls of starting a commercial brewery. What were the prescient decisions that saved the day or the errors of omission or commission that caused an otherwise promising enterprise to careen tragically off the rails?

Hmmm… a tad particular, no? A wee bit off the point of the plan. Seeking business advice from beer bloggers? Let’s see. What did Stan write? Oh, cheater pants. He inverted the question and pointed out how brewing the beer is not the easy part. Good thing that is true or I would have a real issue with Stan this month. A real issue.

So, …”first-hand knowledge of the complexities and pitfalls of starting a commercial brewery.” What can I say. You could do worse than read the blog How to Start a Brewery (in 1 million easy steps) from one of Canada’s more successful craft brewers, Beau’s. Go look at the beginning, 25 May 2006 when they were about 65 employees smaller. Here’s the first batch being brewed. Here’s when the yeast died at the customs office. Read on. You will likely find there were no prescient decisions. There was panic and scramble, beer and patience. And luck. Lots of luck. And good taste and humour. Brewers who lack the skills at those sorts of things, well, don’t make it.

Oh, I cheated as much as Stan did. Damn. I’ll have to have a word with myself.

That is Alcohol and its Role in the Evolution of Human Society by Ian S. Hornsey. I had no idea. In a work of beer writing that is still trying to find its way, seeking to evolve from fanboy gushing or trade focused boosterism or underdeveloped efforts at business journalism, Hornsey’s 2004 book

That is Alcohol and its Role in the Evolution of Human Society by Ian S. Hornsey. I had no idea. In a work of beer writing that is still trying to find its way, seeking to evolve from fanboy gushing or trade focused boosterism or underdeveloped efforts at business journalism, Hornsey’s 2004 book

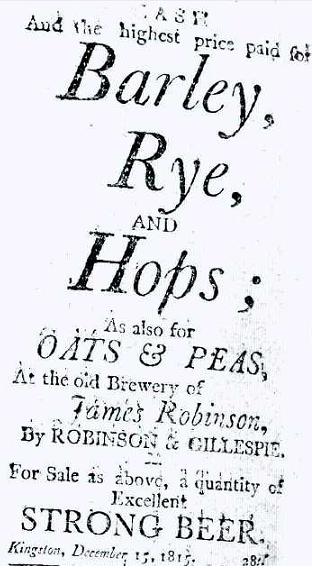

The ad is from

The ad is from